Fifty years ago today the final Sunbury rock festival collapsed

Fifty years ago today it seemed the local music scene was doomed, and those who appreciated good rock music believed the Sunbury rock festivals were the salvation – but the Countdown was on.

Australia started 1975 with more of the same plus a few shocks. John Newcombe won the Australian Open – we’d dominated it for years – in between the double disasters of Cyclone Tracy and the Tasman Bridge collapse. Television was still black and white, like our newspapers. Every governor of every state was a knight of the realm and male. Today none is knighted and all but one are women.

The governor-general was Sir John Kerr, who would make news that year. Now it is Sam Mostyn, who made her name in the fields of gender equity, reconciliation and environmental sustainability – areas on which the hard-drinking Sir John was not known to ruminate.

The Whitlam venture was nearing its end and, in November, Gough would be sensationally sacked as prime minister. Perhaps the greatest legacy, of too few, was his government’s commitment to stimulating the arts. He robustly boosted arts funding, founded the Australia Council, moved on with a National Gallery of Australia, formed the Australian Film Commission, and infamously purchased Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles for a then record $1.1m, which would have bought more than 40 suburban homes in Sydney, the country’s most costly city.

It was then the most expensive American painting ever sold. Whitlam was derided for it, but it is considered one of the most important works of the 20th century and is valued at more than $500m.

Whitlam also helped save rock and roll. His government raised considerably the local content rules for television and radio, and launched 2JJ (now 2JJJ) in January 1975, aimed at younger listening audiences and with a more experimental format. And Whitlam stuck to the 1972 Liberal campaign promise of introducing colour television by March 1, 1975.

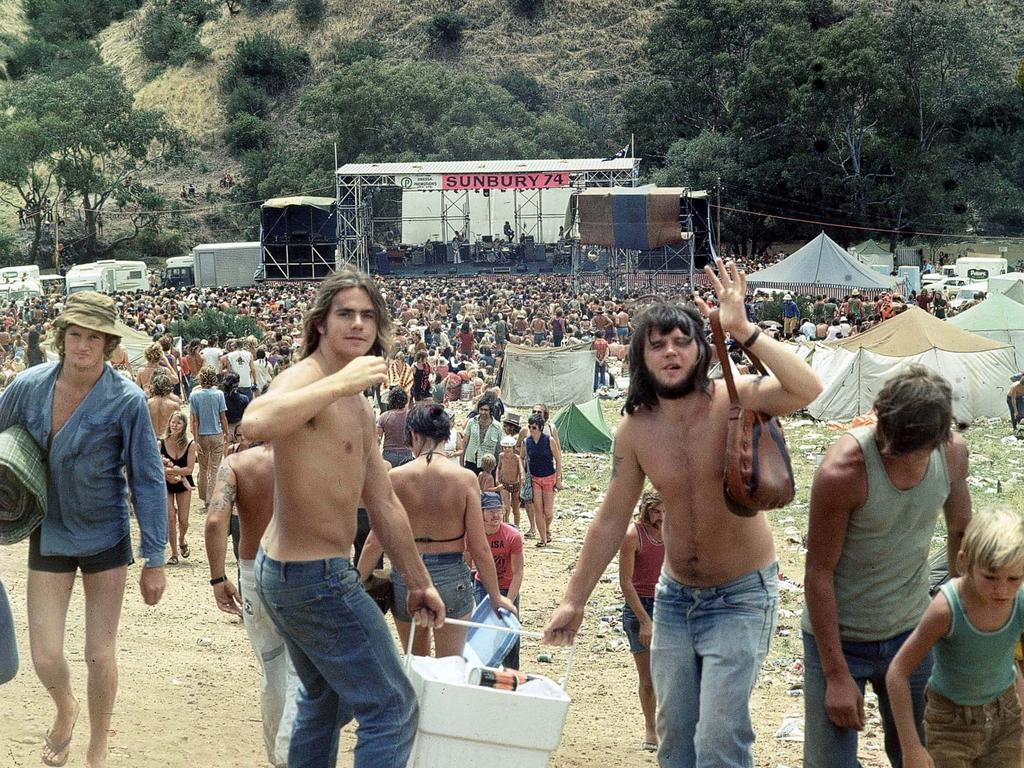

But it was still a black and white world when, over the Australia Day weekend, the fourth Sunbury rock festival was held just outside Melbourne. Older Australians looked askance at young people camping out roughly to listen to music that bore no resemblance to what they heard on the radio.

There were two sides to Australian rock music then: adventurous, progressive but still mostly blues-based bands whose bread and butter was the nascent pub rock scene, and; lightweight groups and singers, often pale copies of the simple pop songs served up from overseas – the sounds that radio preferred.

Just look at the top 40 from the Australia Day weekend of 1975. Heading the chart was Billy Swan’s rockabilly one-hit wonder, I Can Help. Then there was Daryl Braithwaite’s pointless cover of You’re My World, William Shakespeare’s cringeworthy My Little Angel, Pete Shelley’s Gee Baby, The Sweet’s exploitative cover of Peppermint Twist (itself a 1961 dance craze novelty) and Carl Douglas’s disco weird-off, Kung Fu Fighting. (I spotted an amusing T-shirt last year that read “Not everybody was Kung Fu Fighting”.) Elsewhere on that chart were Paul Anka’s frightful You’re Having My Baby, Ernie Sigley and Denise Drysdale’s dire reworking of Hey Paula, and Debbie Byrne’s shallow rendition of Da Do Ron Ron.

Australia needed help. And those who appreciated good rock music believed Sunbury was the nation’s salvation. Over the previous three years it had showcased the solid blues rock and more adventurous sounds seeping from suburban pubs that were calling time later and later.

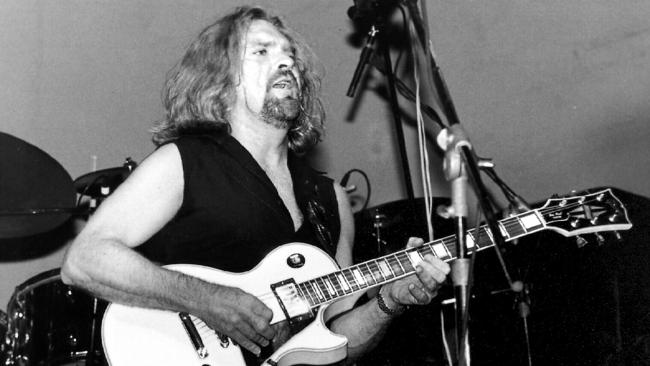

The first festivals were anchored around the calamitous blare of Billy Thorpe’s Aztecs, the nation’s hottest live act. Also there were Spectrum, Madder Lake, Carson, Max Merritt, Chain, Company Caine, Healing Force, Phil Manning and the country’s premier blues and soul singer, Wendy Saddington.

The roster leaned increasingly towards more progressive acts while the festival kept its spine of blues. At Sunbury ’75 there was Ariel, Kush (led by the brilliant and daring Jeff Duff), a still-emerging Skyhooks and former Masters Apprentice Jim Keays performing the whole of his remarkable prog rock solo masterpiece, The Boy From The Stars. But the stars of Sunbury ’75 were the then biggest band in the world – Deep Purple.

After key line-up changes they had a new bass player, Glenn Hughes, and a new vocalist, David Coverdale. But the band was still driven by the fireworks of lead guitarist Ritchie Blackmore and explosive drummer Ian Paice, two of rock’s most admired musicians. By then, their hits in Australia included Black Night, Child in Time, Smoke on the Water, Burn, and the tellingly prophetic most recent single, Stormbringer.

The band was paid $60,000 upfront – the equivalent of more than $500,000 today. And its equipment – Deep Purple were acclaimed by the Guinness Book of Records as the loudest band in the world (Guinness had clearly never heard of Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs) – cost another $100,000 to airfreight to Australia for what was an exclusive one-off performance.

For the first time, the weather forecast for the Sunbury weekend was poor. Fewer than 16,000 people showed when 40,000 or more had been the average. Legend has it that Deep Purple’s huge fee and travel costs bankrupted the festival. That is not so. The truth is that a misplaced rain gauge and dodgy weather reports killed it off. For weather impact insurance purposes, a rain gauge was placed at the Rupertswood Mansion in Sunbury, about 10km from the festival site that was actually at Diggers Rest. It rained at Diggers Rest, but not so much at Sunbury, so the insurance terms were not triggered. Also, Melbourne’s main rock music broadcaster, radio station 3XY, stuck with its outdated forecast of even worse weather so many fewer people from Melbourne – who mostly bought one-day tickets – bothered to go.

Odessa Promotions, which had run all the Sunbury festivals, filed for bankruptcy on the final day.

But for those lucky enough to be there, Deep Purple played a set for the ages starting with Burn and Stormbringer. Of course, the storms had been and gone, and it was a damp but warm night. Deep Purple had been given the right to choose who would perform before them. The band chose Kush and singer Duff. He stayed at Sunbury for the entire three days and thought Deep Purple were magnificent. “They were on fire,” he recalled just this last weekend.

Deep Purple had also demanded that no act follow them for at least 30 minutes. The next act was to be AC/DC whose roadies, unaware of this and eager to cash in on the excitement Deep Purple had generated, moved on stage before Purple’s gear had been removed and, according to who you speak to, even plugged AC/DC’s instruments into the English band’s backline of amplifiers. Both sets of roadies went to war, with Purple’s men prevailing. AC/DC then refused to play.

In the end, with their finances ruined, the organisers were unable to pay any of the local acts. The only performer who didn’t lose out was Keays, whose extravaganza, starring Marcia Hines, Glenn Wheatley and Lobby Lloyde, had been sponsored by a jeans company. That was it. With Odessa in hopeless debt, there would be no more Sunbury festivals. (Generously, later that year, Deep Purple’s management agreed to pay out all the Australian acts at musicians’ union rates.)

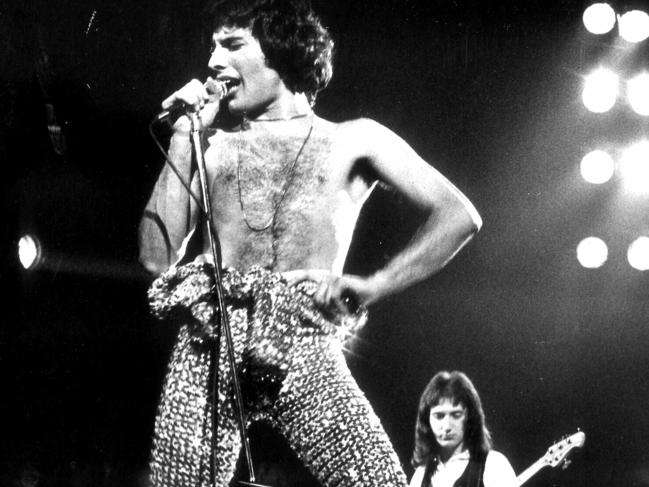

The Australian music scene was devastated. The annual gatherings at Sunbury had been an opportunity to witness what other acts were doing and how they were presenting their music. Little-known British band Queen might have been booed off stage the year before by an audience that wanted the homegrown Thorpe (even if he had been born in Manchester), but people took note of their extravagant performance.

Australian rock bible Go-Set magazine, for which Ian Meldrum was a writer, had closed months earlier, radio was obediently playing lightweight pop, and a deflated frontline of Australian musicians went back to the sweaty pubs that kept them going.

But the past had already shaken hands with the future. Late on Friday, November 8, 1974, the ABC trialled a locally made music television show in the PAL broadcast format that would be the colour television standard come March 1 the following year.

The half-hour show – the first of eight – was hosted by Sydney radio announcer, the late Grant Goldman, and kicked off with a video of UK pop act Paper Lace singing The Black Eyed Boys and included mimed performances by Johnny Farnham, Daryl Braithwaite, Linda George, Sherbet and the then breaking Skyhooks, who sang Living In The ’70s.

By the time Countdown kicked of properly on March 1, 1975 (a Saturday night to coincide with the launch of colour but moved permanently to Sunday the following week), Meldrum was on board as talent co-ordinator but would quickly become the face of Australia’s most successful-ever television show.

It was the perfect convergence of Whitlam’s plans for culture and content. It was Australian music’s anno Domini (AD) and before Christ (BC) moment. A promotional video shown in the days leading up to it had Skyhooks at Melbourne’s Luna Park as the screen went from monochrome to vibrant colour.

Countdown would transform the local music scene over 563 episodes and another 12 years. It would help launch the careers of international acts famously including ABBA, which had provided Meldrum with a reel of songs, all of which became Australian hits first. But Meldrum also championed Madonna, Meat Loaf, Boz Scaggs, Blondie and Cyndi Lauper, whose videos made their songs hits here before they gained traction elsewhere.

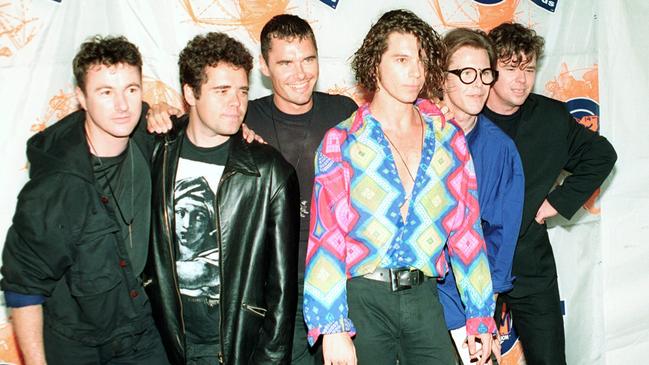

More importantly, Countdown brought into more than three million homes countless Australasian acts, many of which went on to international success that had been enjoyed by so few local performers, including AC/DC, Olivia Newton-John, Icehouse, Kylie Minogue, INXS, Nick Cave, Split Enz and Farnham, who appeared on the first and last shows.

It was bought out and launched on the world in 1981 as MTV.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout