Countdown was the great awakening for my generation

Molly Meldrum and Countdown single-handedly skyrocketed the local music scene and irrevocably influenced the lives of Australia’s youth ... including me.

It arrived with no fanfare. Twenty-five minutes on Friday evening in black and white. But watching the very first episode of Countdown on November 8, 1974 — 50 years ago — lit a fuse in me that burned slowly over that summer.

I’d already been writing reviews of LPs in a street newspaper that I ran — I remember giving Band On The Run quite the rave — but a sliding door moment occurred on March 1, 1975 when Countdown returned, this time in colour, with (then) Johnny Farnham hosting. A band called Skyhooks kicked things off, followed by a skinny Stevie Wright in a red jumpsuit singing Guitar Band.

What, as they say, was not to love? It was an explosion of colour, of short, sharp pop tunes, of garish costumes, and great acts alongside cringe-worthy ones, all charging out of our TVs. As Hush’s lead singer Keith Lamb told me years later, “They were great days, like a carnival”.

With its vibrancy, energy and freshness Countdown was an utter changing of the guard, a farewell wave — if not a middle finger — to the rock and blues bands wearing unruly beards, handlebar moustaches and double denim and playing 20-minute boogies.

For our generation it was the great awakening. Having loved our sisters’ records — Beatles, Stones, Neil Young — this was the start of our own era.

We all knew it too. Share houses across Australia would gather on Sunday evenings and thrill to the quirky mix that Countdown offered every week. For every David Bowie there was a Bucks Fizz. For every The Police there was a Glitter Band. For every Cold Chisel there was a Patrick Hernandez. For every James Taylor there was a Harpo. For every Joe Jackson there was a Joe Dolce. This whiplash-inducing inconsistency was at the heart of the show’s appeal.

My own share house was made up of a group of journalists, a radio panel operator, a real estate agent and several musicians. Two of those were Paul Hester, about to join Split Enz and later Crowded House, and Deborah Conway, soon to crack the charts with Do Re Mi’s Man Overboard and then her solo career. I found references to our days at the share house in Deborah’s recent (excellent) autobiography so I don’t imagine she’d mind me name-checking her.

The witty and sometimes caustic comments about Countdown were liberally offered by this melange of humanity, sitting on ancient couches and surrounded by acoustic guitars, piles of LPs and takeaway pizza boxes. We were the personification of the show’s target audience.

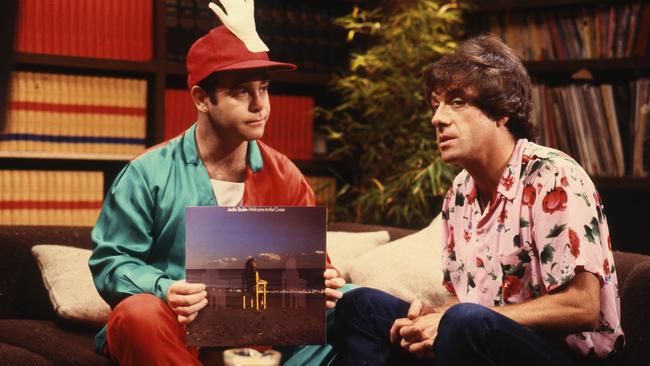

Host Molly Meldrum wasn’t perfect, but he was perfect for Countdown. It didn’t matter that he wasn’t all that articulate — he was a fan, like us. We didn’t have time to stop to work out why we liked The Sweet, or Noosha Fox or Kate Bush or Hush or Supernaut or TMG or ELO or ELP or even OMD. We just did. The show changed many lives. The careers of bands appearing on Countdown on a Sunday night often went into the stratosphere the next week. Countdown certainly changed Molly’s life. He went from being a print journo on Go-Set newspaper to a face recognised across Australia.

And the show changed my life. If country music is three chords and the truth, for a teenage guitar player in the suburbs of Melbourne, it was six chords and a dream: to write about this world.

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of the first episode of that great show, I’ve been reflecting on the road it led me down and who I encountered along the way.

I was soon interviewing the intense Stephen Cummings, the always quotable Jimmy Barnes, the thoughtful, poetic Paul Kelly and Neil Finn, the wry Red Symons, the troubled Stevie Wright, and the scary (but survivable if you were respectful) Renee Geyer.

Over at Renee’s house one day she shared some free character assessment of my new industry. “A lot of the media… are dickheads. Just little blobs of nothing who have too much control over other blobs of nothing. I don’t go up to people and say ‘You’re a blob of nothing’ but they can sniff the resentment.”

I could certainly sniff it, and took due caution. You never left an interview with Renee confused about where she stood.

Other acts were less acerbic. I locked in meetings with Kevin Stanton of Mi-Sex (Computer Games), Roger Hart of Little Heroes (One Perfect Day), Lynda Nutter of WA’s Dugites (In Your Car), Greedy Smith of the Mentals, Doc Neeson of The Angels, Dave Mason of The Reels. Every week a great new band.

I saw a young INXS at Macey’s Hotel in South Yarra perform their first single Simple Simon and headed upstairs with the band after the show where a shy Michael Hutchence shot some pool.

I followed Dragon around on tour in outer suburban Melbourne beer barns, and made the never-repeated error of phoning a rock musician (in this case a member of Dragon) before midday the day after a show. The sound of the curse and the hangup echoed in my ears for a while.

I spoke to a lot of “overseas” performers: Joan Armatrading, Daryl Hall, Leonard Cohen, Iggy Pop, Billy Joel, the B52s. I remember the smallest moments in some of these. Rick Nielsen of Cheap Trick (the guitarist with the baseball cap and bow-tie) gently scolded me for not having done my homework after one question. Back then I thought it was a bit unfair of him, but the fact that his comment still burns today must mean something. I never again went into an interview without some pretty extensive research.

I sometimes received other feedback, occasionally of the robust variety. Don Henley wrote me a letter unhappy about a piece I wrote about the Eagles. Good on him for bothering. It may not have been a peaceful, easy feeling but it was awesome that LA-based rock royalty responsible for one of the most successful albums in history was reading me.

Most turned out well. Some didn’t. Like the actor who forgets all the good reviews but can recite the bad ones word for word, the ones with glitches have stayed with me.

One was a “phoner”. I did a lot of phoners. They were OK, until an incident put me off them. In 1982 I rang Daryl Braithwaite for a feature in Juke magazine. At the end of a good interview I thanked Daryl. I checked the tape. Silence. Forty-five minutes of it.

A sliding door moment: admit it, or think of a plan. I chose the latter. I rang Daryl and asked if we could catch up in Sydney where he then lived so I could “clarify a few points”. It wasn’t complete bullshit — it’s just that I wanted to clarify every point, or to put it another way, do the whole thing again. Daryl graciously agreed. I flew to Sydney from Melbourne and we met in a Bondi cafe.

No-one ever knew of my stuff-up — until right now. The airfare and the payment for the piece was precisely the same. So while I’d done all that work and ended up revenue neutral, I took away a more valuable lesson: check the tape after the first two minutes.

I didn’t check the tape when Bob Dylan agreed to see me backstage at the Palais Theatre in St Kilda. I was possibly too amazed that he’d welcomed me into his backstage dressing room to remember.

How do you get an interview with Bob Dylan? You ask his tour promoter the late Michael Gudinski nicely, and often. As I settled into my seat for the show and the lights dimmed I felt a tap on my shoulder. “Dylan will see you after the show,” said Gudinski, a sentence every music writer wants to hear.

Over 30 minutes Dylan was softly-spoken, took time to answer the questions and was pretty serious, although, unexpectedly, there were a couple of belly laughs. The other side of Bob Dylan indeed.

You learn a lot about big rock stars at unlikely moments. I’d flown to Tokyo to interview Mick Jagger. Of course I’d checked the new tape recorder 30 times in the hotel room. I was led into Jagger’s dressing room as he was being shown some wardrobe options for the evening. “I’ll do that one,” he said, pointing at a jacket.

I asked the first question. Checked the tape. Fine. Pressed record again. It wouldn’t activate. My heart sped up a little. I tried again. If the room wasn’t so dimly lit Jagger would have seen that the blood had drained from my face.

“Go and see if anyone out there has a recorder,” Jagger said. “I’ll try and fix this — I’ve got one of these at home.” I wandered back into the Green Room. Keith Richards and Charlie Watts were chatting around the pool table. No tape recorder around.

I walked back in. Jagger was crouching under a lamplight with the recorder. “Fixed it!” he said. “Anyway if there’s any problem you can come to my room after the show and do the interview then. Looks like you need a glass of wine.”

Jagger opened his personal bar fridge, poured a glass which I shakily accepted.

This was all the confirmation I needed that the higher the talent, the less insecure and more thoughtful.

Nina Simone had a reputation as fierce and occasionally volatile, but in a Melbourne hotel suite she was charming.

What a life she’d led. Her manager tried to wind the interview up just as were getting going. Dr Simone (as she liked to be called) said, “No, he’s doing fine,” she said, waving him away and turning back to me. It must have helped that I had annotated her biography forensically and my questions were good. She looked at me. “Keep going.” I flashed a look to the manager that said, “You heard her, leave us alone”.

Almost all these people appeared on Countdown at some stage in its 13-year history (1974-1987), and I’ve got a TV show to thank for having the chance to speak with them. As the 50-year celebrations gear up, I’m reminded of Graham Greene’s words in The Power and the Glory: “There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.”

And did it come rushing in — Flying V guitars, poodle haircuts, headbands flying all over the place, all quite a sight if you could see them from the clouds of dry ice.

But as hazy as it looked, I could still make out the outline of my immediate future.

Peter Wilmothis the author of Glad All Over: The Countdown Years 1974-1987.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout