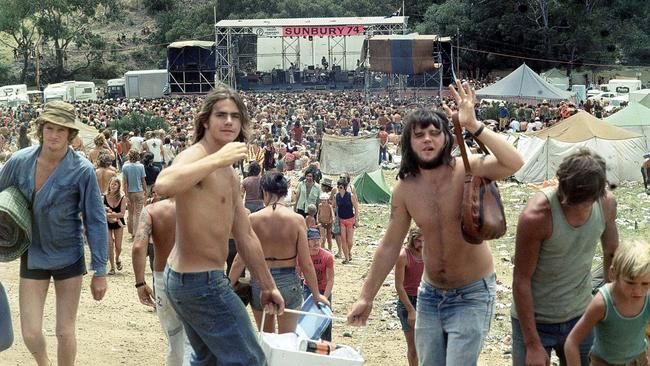

Sunbury was a landmark moment in music, but it was no Woodstock

The Sunbury Rock Festival is routinely described as Australia’s Woodstock; unifying the thoughts and frustrations of a politically charged generation. Nothing could be further from the truth.

After footfall on the moon, Neil Armstrong tripped up. He had meant to say “That’s one small step for a man”, but it came out as “one small step for man”. And much though the world might have wished for it, despite the US’s stupendous achievement that July 20, giant leaps for mankind were less common, particularly in America.

In January 1969, controversial president Richard Nixon was sworn into office just weeks before Sirhan Sirhan, the assassin of the man who might have defeated Nixon, pleaded guilty to killing Bobby Kennedy. Seven days later James Earl Ray admitted having killed civil rights hero Martin Luther King. A hard-left terror group, the Weathermen, emerged whose violent Days of Rage riots were timed for the case of the Chicago Seven, a nasty drawn-out trial pitched somewhere between political and criminal. Starting on August 8, Charles Manson’s Family members murdered seven people, including eight-month pregnant actor Sharon Tate and her friends. Within days Lieutenant William Calley would face charges over the My Lai massacre of 109 Vietnamese villagers the year before.

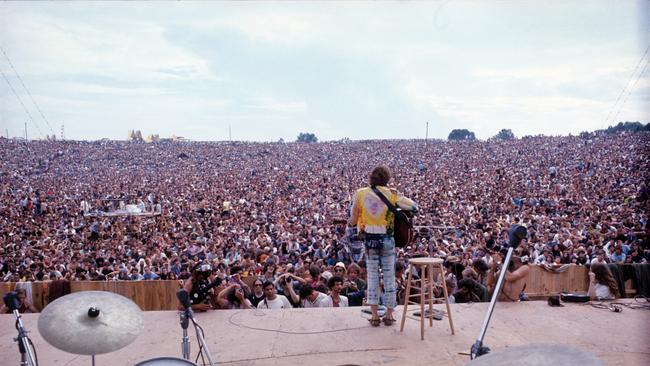

The Woodstock festival that began six days after the Tate murders could not have been better timed. Billed as “an Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music”, and featuring some of the biggest names in rock music, it seemed to unify the thoughts and frustrations of a generation tired of racial and urban violence, self-serving politicians, the war in Vietnam, and who were looking for a new way. The third act on day one was the now forgotten Bert Sommer performing Paul Simon’s America, a song that acutely observes a couple and a country lost and looking for America. It won a standing ovation. Elsewhere the list was studded with anti-war campaigners: Arlo Guthrie, John Sebastian, Joan Baez, and Country Joe McDonald with his amusing I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag with the line “Send ’em off before it’s too late – be the first one on your block to have your boy come home in a box”. At one point Chicago Seven defendant Abbie Hoffman stormed the stage shouting a solo protest, but the Who’s Pete Townshend told him to “F..k off” and raised his guitar to strike him.

Woodstock’s most powerful political statement came without words. The festival’s final act, Jimi Hendrix, with minutes to go and unannounced, bent the Star-Spangled Banner out of shape in a jolting condemnation of where his nation was headed. Jose Feliciano had performed a gentle Latin reworking of the national anthem the year before at the World Series and the absurdly indignant reaction to it ruined his career. Veterans took of their shoes and threw them at the TV. Hendrix – himself a veteran of the 101st Airborne Division – had his Fender Strat tell the story with a feedback-charged attack that included distorted sounds of helicopters, gunships and staccato rifle shots until he fell silent and returned for the last line, which the audience, to a fan, knew was “O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave”. It would make the Sex Pistols’ God Save the Queen sound like music hall.

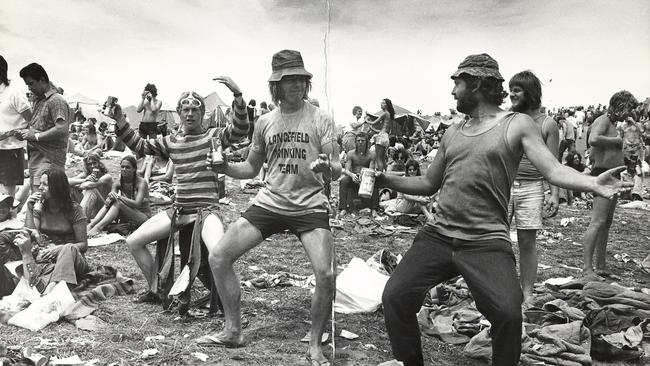

The Sunbury Rock Festival that took place 50 years ago this weekend is routinely described as Australia’s Woodstock. Nothing could be further from the truth, unless large crowds drinking beer in a field with bands on stage is everybody’s Woodstock. Woodstock was a complicated statement of intent and wishful thinking where the artists spoke through music, if naively at times.

Sunbury was simple. And, mostly, so was much of Australia then. We hadn’t quite woken up. And it’s not as if we didn’t have a lot to wake up and be angry about. We had a prime minister in Billy McMahon who shamed us but who had somehow advanced by favour or mistake – it was never clear. He was described by his decades-long colleague and governor-general Sir Paul Hasluck as “disloyal, devious, dishonest, untrustworthy, petty, cowardly”. Add to that “thief”. He tried to steal legendary reporter Laurie Oakes’s tape recorder. “It’s mine,” McMahon said, presumably sounding like Gollum trying to claim the Ring. But Oakes snatched it back, noting that it had his employer’s call sign engraved on the front.

McMahon had humiliated Australians when, in that reedy voice that commanded no one, he drifted from the words he had practised for a White House speech before Nixon. Attention was waning, as always, so he sought to inject some life into it by quoting Brutus’s famous words from Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar but he couldn’t remember them: “I take as my text a few familiar words – that there comes a time in the life of man in the flood of time that taken at the flood leads on to fortune.” An Australian reporter there muttered: “I wish I was Italian.”

For two years some of our biggest demonstrations, the anti-Vietnam War moratoriums, had paralysed our state capitals as hundreds of thousands marched to end a conflict we could not win. More than 500 Australians died there, and the government of the day – in office for 22 years by the time of Sunbury – had overseen it all.

Over the winter of 1971, the all-white Springboks had been allowed here for a rugby tour. The brutal South African apartheid system saw the country’s black majority ruled out of a role in their future. The system was to guarantee whites held sway over wealth and privilege. Students joined with Indigenous activists and unionists to disrupt the Springbok matches.

Before the visitors arrived it was reported up to 85 per cent of Australians supported the visit. The troubling scenes of violence divided Australians, many of whom perhaps thought for the first time about the viciousness of South Africa’s rulers who determined where blacks could live and who they could marry as millions were “resettled” into segregated areas.

The Springbok protests – with violence on each side – didn’t stop any games but the Australian Cricket Association, led by Don Bradman, called off the summer Test cricket tour and said we wouldn’t play again until their teams were selected on a non-racial basis.

Indeed, no team would come until Nelson Mandela was released from jail. The boycotts – sporting in particular – worked. Not that in 1971 – the year Neville Bonner became the first Indigenous Australian in the parliament, and Evonne Goolagong was Australian of the Year, and Walkabout was released – the lives of Indigenous Australians were fair or fulfilled.

American life pulsed with the era’s politics, many of its issues running parallel with ours. We were just gaining momentum and our thoughts were less regularly expressed in popular culture (but neither did Australians assassinate political enemies). On the final day of the first Sunbury, McMahon had 306 days left as prime minister. There was something in the air, but little evidence of it at Sunbury.

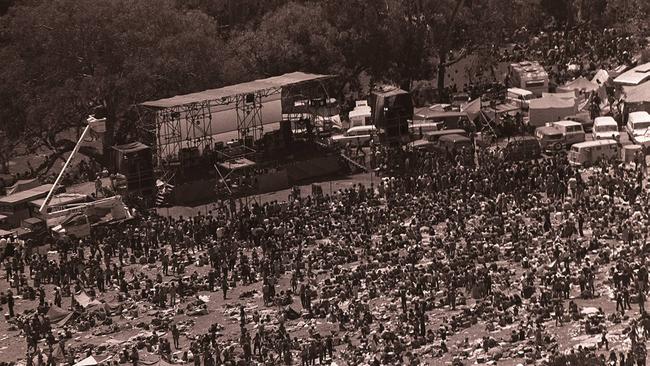

The event, an idea formed in the canteen at Channel 9’s Melbourne studios, then in Richmond, had been modelled on Woodstock. A field was foundinn Duncans Lane, a lonely dead end in farmland on Jacksons Creek at Diggers Rest, 33km northwest of the city. No one thought Diggers Rest had a ring to it. The adjoining town was Sunbury – summer, sun – it all made sense.

Bravely, mostly Australian acts were booked, a statement in itself. But 1971 had been the year when Australian rock music came of age. After years when local acts too often recorded pale interpretations of overseas hits the scene changed almost overnight with Spectrum’s brilliant, bluesy single I’ll Be Gone (the video for which coincidentally had been filmed near the Sunbury site). It topped the charts in April 1971 opening up the floodgates.

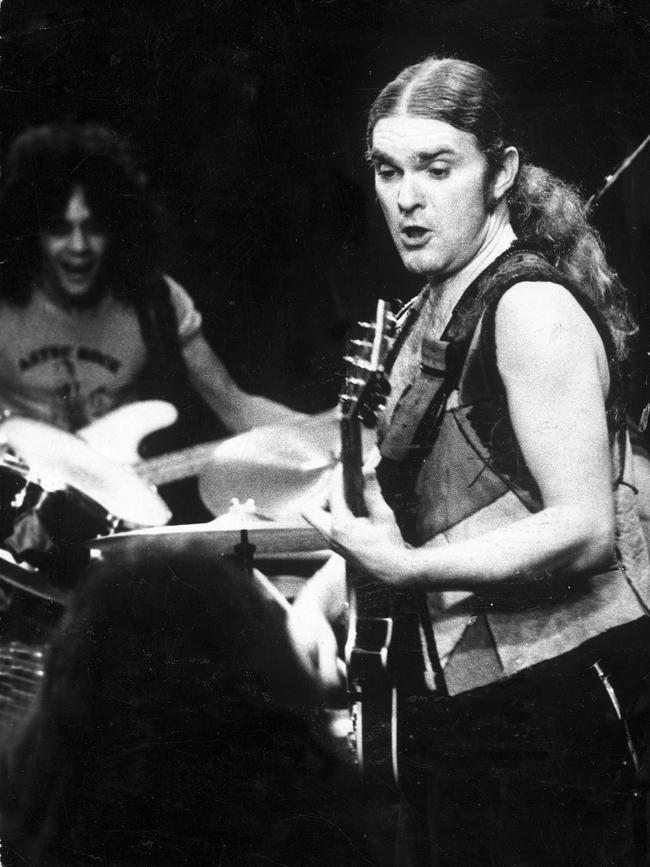

Soon after, Daddy Cool’s Eagle Rock dominated airwaves and stuck immovably at No.1 for months. Australian acts were suddenly all over radio in the second half of that year: Russell Morris (Sweet, Sweet Love), Axiom (Fool’s Gold), Healing Force (Golden Miles), Chain (Judgement), Hans Poulsen (Natural High), Colleen Hewett (Day by Day), Sherbet (Free the People) and Billy Thorpe (Dawn Song).

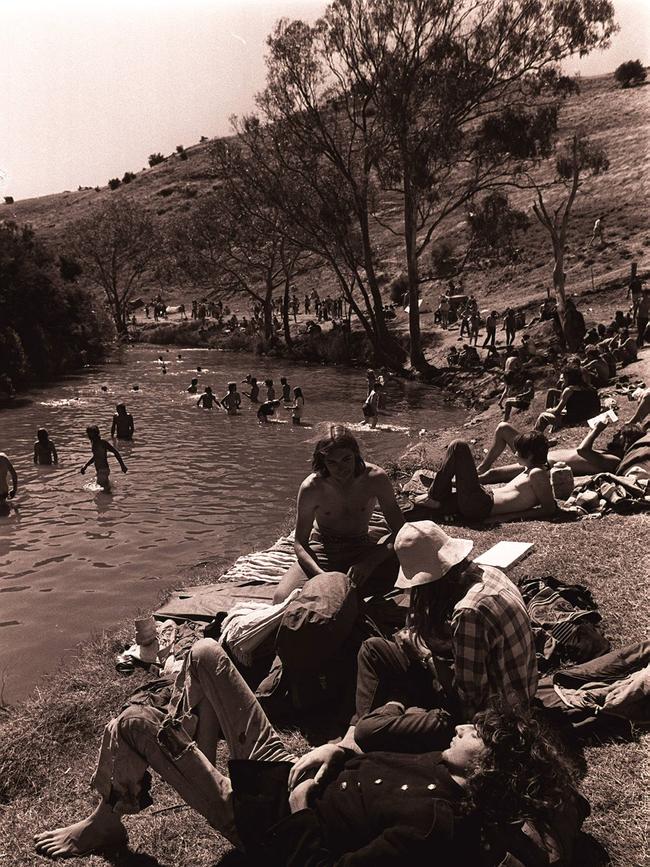

Watching videos of the first Sunbury can be deceptive. Woodstock was filmed in colour and is recalled in kaleidoscopic detail. Sunbury’s music fans arrived in tired 1960s cars or trudged 2km from the railway station, having arrived in rickety carriages that bore the legends “Smoking” and “No smoking”. Many had alarmingly few possessions – a few blankets, the occasional polystyrene Esky, dodgy canvas tents, rolled-up sleeping bags, a few clothes, some food, or maybe not. For some, the $6 ticket meant they had no money once there, and no food. The Salvation Army had anticipated this and set up a tent to provide for the bankrupt and hungry.

The brief hippie era was over and a homegrown phenomenon was emerging but not yet fully formed (that would take changes to liquor licensing laws) that we recall as pub rock. This would be driven largely by the bands that appeared at Sunbury, particularly Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs. As a showcase of the adventurous local music scene, Sunbury could not have been more successful with sets by proto-progressive rock acts Madder Lake, Pirana, Tamam Shud, MacKenzie Theory, Spectrum and the Indelible Murtceps (Spectrum spelled backwards, both bands headed by the intrepid Mike Rudd). But the closest it came to any social discourse was an illuminated peace sign above the stage.

It was neither counter nor culture. At one stage activist and artist Benny Zable turned up – he turned up everywhere – and danced around with long streams of white fabric (but possibly plastic) in front of the stage. He looked odd. People gave him a wide berth. But he was hardly Abbie Hoffman.

If things were changing, the complacent Sunbury crowd and its sea of cans and bottles gave no hint. The following year saw a burgeoning awareness of ourselves and our ways, even with the cliched, innocent-abroad Adventures of Barry McKenzie. Towards the end of the year the ABC launched The Aunty Jack Show, the cult status of which is undimmed. Thea Astley won the Miles Franklin Award – again – this time for another relentlessly Australian themed novel, The Acolyte. The Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established and Doug Nicholls became the first Indigenous Australian to be knighted.

The Whitlam government came to power on December 2 and changed the country with unheralded speed. Gough Whitlam and his deputy, Lance Barnard, formed the first Whitlam ministry, Whitlam holding 13 ministries, Barnard 14. They vowed to return our remaining troops in Vietnam “by Christmas”, suspended National Service and freed jailed draft dodgers, set about recognising China, acted on equal pay for women, rejected membership of the Privy Council of the UK, cut ties with the colonial remnants of Rhodesia and removed sales taxes on the pill. The would go on to axe university fees, introduce Medibank, establish the Australian Film Commission, work on urban renewal and lower the voting age to 18.

Suddenly, that age group – dormant at Sunbury – showed some interest in politics, led there by the revolution in Canberra. The noisy Woodstock generation had the Oval Office watching them and listening to them carefully and with interest. Whitlam’s government said “Look at me”. But when the 18-year-olds voted for the first time in 1974, Whitlam’s modest majority was reduced. And in 1975, by the close of the final Sunbury Rock Festival, Whitlam, increasingly seen as a tarnished hero of lost hopes, had just 297 days left as prime minister. Not even a sympathy vote after the Dismissal would help. Whitlam had fanned these sails. Then the ship left without him.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout