WOMADelaide: it’s out of this world

The gutsy, spectacular four-day celebration of music, arts and dance, is celebrating its 30th birthday. And the world plans on coming to the party.

Archie Roach had never seen anything like it. Neither had his fellow musicians Paul Kelly and David Bridie, who were also on the bill, or any of the 10,000-per-day attendees of a festival held amid the giant ghost gums and ancient Moreton Bay fig trees of Adelaide’s Botanic Park.

The year was 1992. The event was the curiously monikered WOMADelaide.

“A spectrum of world sounds in one weekend,” they’d tagged it, helpfully, priming music lovers for an eclectic array of artists from locales far-flung and closer to home, for names largely unknown and often tricky to pronounce.

Held as part of the then biennial Adelaide Festival of the Arts, WOMADelaide was jointly presented with WOMAD UK, the festival co-founded a decade previously by famous English rock musician and former Genesis frontman, Peter Gabriel.

“Pure enthusiasm for music from around the world led us to the idea of WOMAD (World of Music, Arts and Dance),” said Gabriel early on. “Music is a universal language. It draws people together and proves, as much as anything, the stupidity of racism.”

Non-western artists were being enthusiastically embraced in the UK and Europe by aficionados of “world music” – a marketing label invented by some music promoters in a London pub in 1988 and long past its use-by date now. But in those misty pre-Internet, pre-global travel days Australia was far away, and more than a little behind.

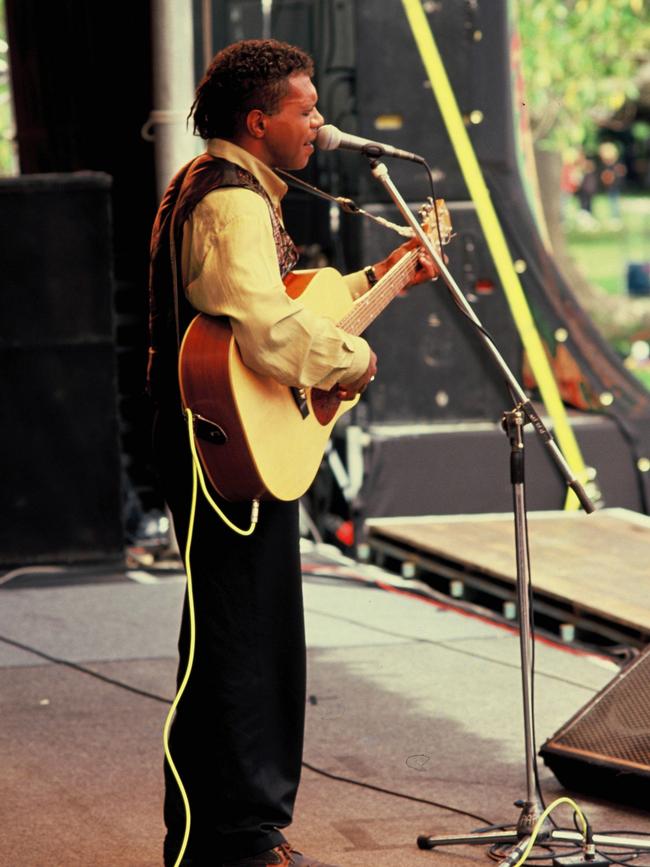

“WOMADelaide was huge for me,” says Roach, who had just released his solo debut, Charcoal Lane, co-produced by Paul Kelly and guitarist Steve Connolly, and was surprised to draw a large crowd.

“I wasn’t well known but people hung around and the vibe was great,” he says. “The line-up was incredible. I loved getting to see all these amazing singers and musicians I’d never heard of.”

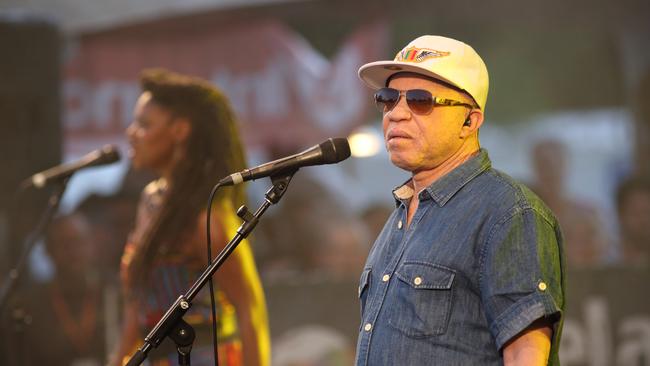

Among them, ribbon-headdress wearing Bulgarian vocal ensemble Trio Bulgarka; Guo Yue, a UK-based virtuoso of the Chinese dizi bamboo flute, and Ayub Ogada, a singer and nyatiti lyre player from Kenya in East Africa discovered by Gabriel’s Real World Records while busking on the London Underground. Rising star singer Youssou N’Dour from Senegal in West Africa was there, having appeared on Peter Gabriel’s platinum-selling So album in 1986 and joined him on a subsequent world tour. “His voice is like liquid gold,” said Gabriel then.

There, too, also with an album on Real World (1990’s Michael Brook-produced Mustt Mustt) was Pakistan’s Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, a heavyset icon who sat cross-legged on a carpeted platform with his multi-generational ensemble, gesturing, trancing, sending his devotional Sufi Qawwali songs skywards.

“On my 30th birthday, at midnight, a group of us sat under an enormous ghost gum listening to Nusrat,” Bridie says. “I’d been staying in the hotel room next to his, in a 3-star with a Gideon’s Bible, instant coffee sachets and dodgy bed springs, and had earlier seen this very big man being helped into his van by staff. To then experience this Sufi Qawaali master live and larger-than-life, his group’s cascading vocals, harmonium surges and frenetic tabla playing wafting across the park, was mesmerising. Just being on-site felt ground-breaking.”

Bridie’s band Not Drowning Waving was on the bill with several musical collaborators from Rabaul in Papua New Guinea including singer/musician (and later, ARIA award-winner) George Telek, who features on their 1990 album, Tabaran. “There was a sense that performers from other cultures were finally being given recognition in the southern hemisphere, even if it was a few years before organisers curated the strong First Nations Australia and Pacific line-up it has now,” Bridie continues. “It was a real eye opener for Telek to see PNG cultural music standing alongside international artists of this ilk.”

WOMADelaide was only meant to be a one-off. A way for Adelaide Festival director Rob Brookman – who only got one shot at the program, as was then customary – to present a mini-festival of artists outside the confines of the concert hall. It also provided a solution to a mounting problem: too many fabulous musicians, too few venues to put them in.

“I was looking at doing 20 concerts in Adelaide Town Hall, each one competing with the other for ticket sales, when the idea of a festival within the festival struck,” says Brookman, newly retired after a 45-year career in the arts including three years as Adelaide Festival executive director.

“Then I read a tiny article in (British entertainment newspaper) The Stage about this WOMAD event taking place in the UK. I thought, ‘That’s exactly what I’m thinking of doing!’ So I sent off a fax then got on a flight and met with organisers.

“It was fantastically exciting to see an audience embracing music that was perhaps completely alien to them,” he continues, “whether it was a kora player from Mali, a Tex-Mex accordionist or lyrics being sung in Ethiopian Amharic.”

WOMAD was already a franchise, with festivals in 10 countries; a WOMAD in Australia made sense. Alongside the artists from the pre-existing WOMAD circuit Brookman folded in acts from his Adelaide Festival program including the Mapopo Acrobats of Kenya – also performing in a Big Top pitched outside the Adelaide Festival Centre – and Indian classical violinist L. Subramaniam.

A site was found at Belair National Park, 13km south of Adelaide. Tickets were printed, advertisements taken. Then came the late realisation that in the event of a Total Fire Ban, Belair Park would stay closed.

Tasked with finding a new site fast, Adelaide Festival general manager (now WOMADelaide director) Ian Scobie drove about armed with a Gregory’s street directory until he reached Botanic Park next to the Botanic Gardens – where the Adelaide Festival had staged the Vietnamese Water Puppets in 1988.

“Mounting the festival in a beautiful environment was vital to us,” says Brookman. “Botanic Park was a natural fit. WOMADelaide would be the first festival to pay attention to things like separating waste streams and later, carbon neutrality. But for that first one I was just worried that people would come.”

WOMADelaide would herald a new era of large-scale, outdoor performances with multiple stages and a multiplicity of voices – the inaugural Big Day Out also took place in 1992 – doing away with the need for headliners. Nonetheless, Crowded House was added to that tyro bill as an insurance policy, a high-profile stamp of approval for the quality of the music contained within. “Crowded House sounded pretty strange in that context because everything was so rich culturally,” remembers Bridie. “But they seemed in awe of the other musicians on the bill and put on a great acoustic show.”

WOMADelaide was a world in a park. A model of cross-cultural connection and understanding, of a society we might want to live in.

It was no wonder, really, that organisers jumped onstage at its conclusion and – surfing the wave of gratitude – pledged that it would return the following year. The logistics of which they didn’t think about, other than that they’d think about them later.

“Everybody wanted WOMADelaide to continue,” Paul Kelly says. “There was such great excitement about these artists singing in their own languages, playing their traditional instruments, conveying messages that you felt you understood.”

In March, WOMADelaide turns 30. What began with three stages and collectively crossed fingers has evolved into an annual four-day, seven-stage extravaganza, a premier league event that has grown and developed alongside its audience, facilitating change, sparking discovery, bolstering SA tourism.

Welcoming A-list artists from Miriam “Mama Africa” Makeba and Salif Keita, the Malian Caruso to Ravi Shankar, the legendary Indian sitarist who influenced the Beatles. Grammy-winning Angelique Kidjo from Benin to Nigeria’s Seun Kuti, son of Afrobeat icon Fela Kuti, fronting his father’s band Egypt 80. Youssou N’Dour, returning in 2015 as a superstar and elder statesman, even performing a surprise duet (on the 1994 hit Seven Seconds) with UK singer Neneh Cherry.

It has hailed R&B queen Mavis Staples. The AfroCuban Allstars. Jimmy Cliff. The Specials. The Cat Empire. Gurrumul. Chic. More. Three decades’ worth of stories, woven into the fabric of the festival: stories told through art and music, personal and cultural histories, through community workshops, onstage interviews, and artist-led cooking sessions. Relayed after dancing to late-night DJs in a pine forest with a natural dance-floor, or while gathered under the giant fluttering silk flags on poles that have become a WOMAD insignia.

Stories created backstage, behind the scenes, beyond the festival gates: of the challenges of flying people in from, say, Yakutia in Siberia (vocal trio Ayarkhaan) or Nouakchott in Mauritania (diva Dimi Mint Abba). Of officials tasked with clearing items made from skins, shells and horns or, in the case of French aerial company Gratte Ciel – whose spectacle Place des Anges was a controversial highlight of 2017 WOMADelaide – thousands of kilograms of duck feathers.

Stories that have become legend: the impromptu backstage football match involving Irish band Kila, the Drummers of Burundi and berobed members of Baaba Maal’s Senegalese entourage. An ecstatic Xavier Rudd taking his final applause while swinging diminutive compere Annette Shun-Wah above his head. Or the time Botanic Park was invaded by tiny grasshoppers: “If one of those things goes into my mouth, I walk,” declared US singer/harpist Joanna Newsom.

Or indeed, the chance headline slot by Peter Gabriel in 1993, which helped to secure WOMADelaide’s future. “We were very lucky to get Peter,” Brookman says. “He had a rare free date just before he was attending the Grammys, so we shared travel costs. If 1993 hadn’t worked, it would have been all over.”

The profit made in 1993 went into bolstering the next WOMADelaide in 1995, an alternate year to the biennial Adelaide Festival.

Until WOMADelaide went annual in 2004 (the Adelaide Festival waited until 2007), gap years were peppered with one-off WOMADelaide events including the 1996 Indian Pacific train trip from Perth to Adelaide, with a stop-off concert in the remote settlement of Pimba. On board, rubbing shoulders with paying customers, were the Bauls of Bengal, Tuvan throat-singing outfit Shu-De, Scottish lesbian-country band The Well Oiled Sisters and Archie Roach and his late wife and creative partner Ruby Hunter: “When we came offstage all these old Pitjantjatjara and Kokatha people swamped Ruby and told her they were her family through her grandfather,” he says. “It was beautiful.”

Kelly, also there, remembers collaborating prolifically en route: “The Tuvan throat singers jammed with me on my song ‘Maralinga’ (about the scene of British nuclear tests in the 1950s). Sitting next to a person who is singing two drones through one mouth is wild, especially when you’re passing through country where the story of the song happened.”

Roach and Kelly have both gone on to play WOMADelaide several times over. In 2021, in the midst of a global pandemic, Roach headlined the opening night of WOMADelaide’s four seated concert evenings at King Rodney Park, singing the songs of Charcoal Lane (an album he re-recorded at his kitchen table during lockdown) in a farewell show that felt like a spiritual bookend.

“It was deadly to get back up on stage, and the crowd was great,” Roach says. “WOMADelaide was where I began sharing my music and stories and connecting with the people coming to see me. It’s great that it is still going strong. Here’s to another 30 years.”

The 30th anniversary line-up comes invested with an international feel and a distinct sense of national pride.

Among the overseas visitors, Brazilian jazz-funk trio Azymuth, LA-based Guatemalan singer-songwriter Gaby Moreno and UK DJ Floating Points stand out. For the most part, however, the program is domestic based: Courtney Barnett. Yolngu surf rockers King Stingray. First Nations rappers Baker Boy and rising star Barkaa.

Electric Fields and their in-language club anthems. Melbourne-based South Sudanese star Gordon Koang and his loud, locally sourced band of indie musicians. Cairo-born Australian oud player Joseph Tawadros, performing his Concerto for Oud and Orchestra with the 52-piece Adelaide Symphony Orchestra.

It’s a bill that is testament to the evolution of WOMADelaide. To its transformation from a curiously named event with, at first glance, an even curiouser line-up, into a festival that is now a brand, a byword for quality, a celebration greater than the sum of its parts.

“We’ve become so used to accessing music from all over the world, and going to all sorts of eclectic festivals, that we forget how pioneering that first WOMADelaide was in 1992,” Kelly says. “It changed the musical landscape. Thirty years! That is pretty astounding. I will definitely be honouring that.”

WOMADelaide runs from March 11-14.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout