Extraordinary lives of passion and purpose

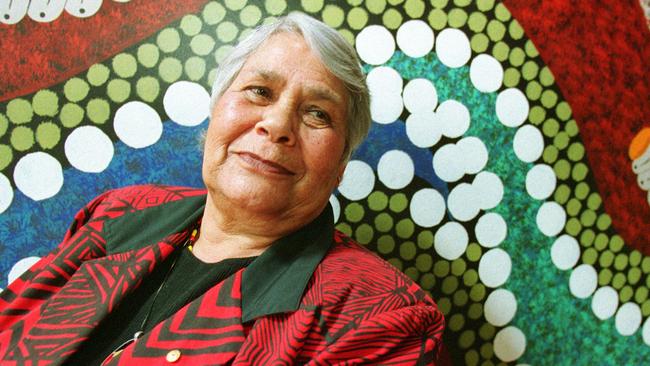

We honour Indigenous leader Lowitja O’Donoghue and playwright Ray Lawler, giants of Australia’s 20th century cultural landscape.

Two Australians who died this year changed us in different ways, but each helped shape the very idea of Australianness, both starting in the unhurried days of the mid-1950s Menzies government.

It is inadequate to describe Lowitja O’Donoghue using the word activist because she was active in so many ways that sometimes brought her people front and centre of the national consciousness.

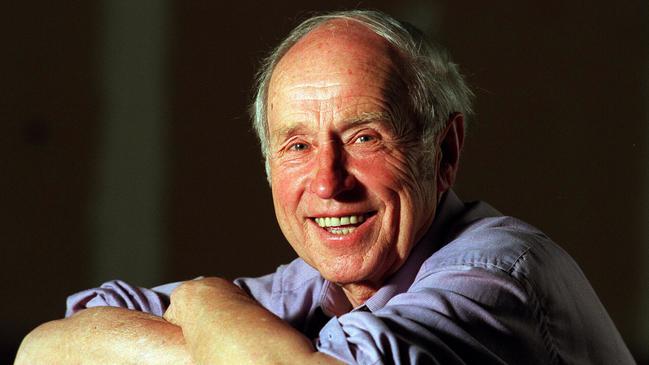

Unassuming playwright Ray Lawler was also born in poor circumstances and similarly educated himself out of them. His third play, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, was first staged in the year Labor, still led by HV Evatt, split in two.

In 1982, Shane Howard wrote the words to Goanna’s hit song, Solid Rock: “Out here nothing changes, not in a hurry anyway.” He could well have been writing about early ’50s Australia.

But O’Donoghue and Lawler gave history a hurry-on.

O’Donoghue was born in the far north of South Australia on a cattle station called De Rose Hill. Her birth was unregistered and she was given the birthdate of August 1, 1932. Julia Gillard was born 29 years later in Barry, Wales, a dull seaside town on the Bristol Channel.

The odds of them ever meeting were astronomical. When they did, O’Donoghue was the retired former chairwoman of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission and Gillard was prime minister.

Gillard helped launch O’Donoghue’s biography in 2020 and said on O’Donoghue’s death on February 4, aged 91, that “she was funny”. “Even in her old age, she has a rare magnetic energy. Those special qualities and her remarkable intelligence made her an incredible advocate,” said Gillard.

By then O’Donoghue had spent decades leading Australia’s Indigenous community in key roles: regional director of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs in South Australia, a member of the Aboriginal Rights Movement, chairwoman of the Aboriginal Development Commission, founding chairwoman of the National Aboriginal Conference and then founding chairwoman of ATSIC – prime minister Bob Hawke’s vision for an Indigenous-run future for Indigenous Australians – a role she held for six years until 1996. On her watch it worked well and, while it was abolished in 2005, she did not live to see the architect of its demise, Geoff Clark, jailed for six years and two months for defrauding his community of almost $1m.

O’Donoghue helped draft the Native Title Act 1993 after the High Court rejected in its Mabo decision the notion of terra nullius and ruled that Indigenous Australians had not had their land rights extinguished by colonisation.

As she made clear, she was not stolen but removed from her mother and sent by her father to a United Aborigines Mission. He had sent two of her older siblings a few years before. They were reunited before the mission moved to Quorn in the Flinders Ranges. She was never able to forgive her father and it was 33 years before she was reunited with her mother, Lily, who, cruelly, had no idea where her children had gone.

The mission, always short on water, moved again in 1944 to Adelaide, which enabled O’Donoghue to attend Unley High School, a hothouse of South Australian talent whose alumni includes premiers John Bannon and Dean Brown, Peter Coleman (he invented the flu fix Relenza), and Mark Oliphant (a former governor of the state and key researcher in the development of radar and nuclear fission). And, of course, Australia’s first and only female prime minister.

After school she went into domestic service for two years. She trained in nursing at the Royal Adelaide Hospital, whose reluctance to employ her was overcome only with the help of legendary premier Thomas Playford, the longest-serving political leader in Australian history. After graduating she worked in India for the Baptist Overseas Mission. On returning she took up the first of her many government posts, first with the South Australian Department of Education as a welfare officer.

She moved to the Office of Aboriginal Affairs, gaining valuable experience in how a federal department operates. In 1973, prime minister Gough Whitlam formed the National Aboriginal Conference – a voice to parliament before Anthony Albanese had left primary school – and when this was refashioned by Malcolm Fraser, O’Donoghue was put in charge.

In 1992, as part of the UN International Year of Indigenous Peoples, she addressed that forum, becoming the first Indigenous Australian to do so. She said she was considered by prime minister Paul Keating for the role as 22nd governor-general of Australia but turned him down. A republican, she would not live in “the queen’s house”. Keating denies the offer was made.

As an adviser to the Sydney Olympics, she bore the Olympic torch by Uluru, she helped draft Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations. In 1976 she was the first Aboriginal women to be given an Order of Australia, seven years later was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire, and she was 1984’s Australian of the Year, a position she took in the hope of using it to change the date of Australia Day.

Weeks before he died, Pope John Paul II made her a Dame of the Order of St Gregory the Great.

On her death, Albanese said she was “like a rock that stood firm in the storm – sometimes even staring down the storm. More than anything, she was one of the great rocks around which the river of our history gently bent, persuaded to flow along a better course”.

In 1979, she married Gordon Smart, 14 years after she met him working in Adelaide’s Repatriation Hospital. “I kept him waiting for years and years,” she remembered in 2014. The couple had no children. He died in 1991.

Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll was not just a profound cultural landmark, but the first Australian play to be performed internationally, more remarkable given it is set in the then working-class inner northern Melbourne suburb of Carlton in 1953 and that the sugarcane cutters at its heart spoke in an Australian vernacular that rarely made the stage. It was immediately successful across Australia and then in London (where future Visy billionaire Richard Pratt was one of the actors) but the cultural gulf was too wide for Americans, whom it confounded. Nonetheless, an Americanised version of it was filmed using a miscast Ernest Borgnine, John Mills and later Murder, She Wrote star Angela Lansbury. The pedestrian script was by English writer John Dighton, who admitted he didn’t like the play and titled his version Season of Passion.

But Lawler, who died on July 24, aged 103, saw his play change the course of Australian theatre.

One of eight children, he’d been born to working-class parents in Footscray, an inner western Melbourne suburb in 1921, and went to work as a labourer in a local factory aged 13. He stayed there more than a decade, but studied acting and at 25 wrote his first play. He slowly wrote another, which was performed six year later. In 1955 he completed the acclaimed Summer of the Seventeenth Doll, which won the now forgotten National Theatre Competition.

This critical milestone in creative writing was a sensation and has been performed across the globe, twice filmed for television, and translated into many languages. After living in Europe for many years, Lawler was invited to return to Australia to be associate director of the Melbourne Theatre Company – as long as he stretched Doll out to a trilogy.

The first play, Kid Stakes, predating the Doll story, made its own cultural impact. One of its characters repeats a phrase common in 1930s Port and South Melbourne – “Up there, Cazaly”. Singer Mike Brady attended an early showing and went home with the idea for a song.

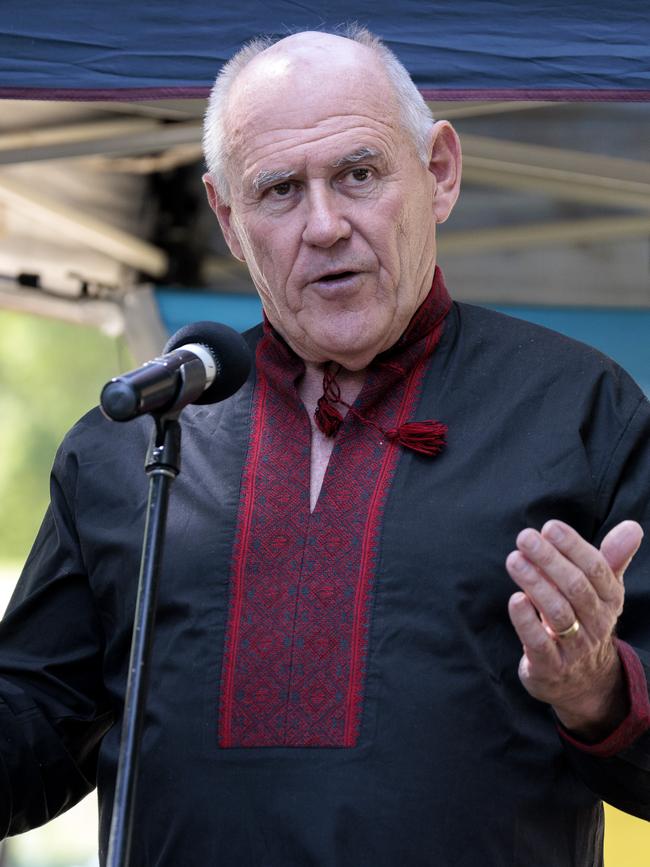

STEFAN ROMANIW

(Nov 12, 1955-June 26)

Two Australian Prime Ministers and four Victorian Premiers attended or were represented at the state funeral of Stefan Romaniw in July. He died after falling ill at Warsaw Airport returning to Australia after a meeting with Ukrainian leader Volodymyr Zelensky. A former Multicultural Commissioner in Victoria, no one did more for the Ukrainian diaspora in Australia and internationally or for the promotion of languages in Australia.

MAGGIE TABBERER

(December 11, 1936-December 6)

Spotted by the photographer at her sister’s wedding, she became a model and won Model of the Year in 1960 mentored by legendary German photographer Helmut Newton. She started her own PR firm in Sydney while writing on fashion for the Daily Mirror. Over 16 years there she appeared on Beauty and The Beast winning Gold Logies in 1970 and 1971, the first to take successive awards.

IGNATIUS JONES

(October 24, 1957-May 7)

He attended school with another outlier, Tony Abbott. Both had luminous intelligence that found expression in unalike ways. We first heard him on Jimmy and The Boys’ single I’m Not Like Everybody Else. We never said he was. He is remembered for organising big events – Gay Games, Sydney’s Olympics ceremonies, and the New Year’s fireworks. On Countdown he was wheeled in by his drag-queen keyboards player, gagged and tied to a chair.

PHYLLIS O’DONELL

(1937-November 6)

She had never been on a surfboard until aged 23. She and her sister bought one from the now defunct hardware chain Nock & Kirby. They took it to Sydney’s Harbord beach and paddled it about. Her sister lost interest. She stuck at it and became famous at Manly, clearly the best surfer on its beach. In 1964 the first world’s women championships were held there. She was the planet’s best.

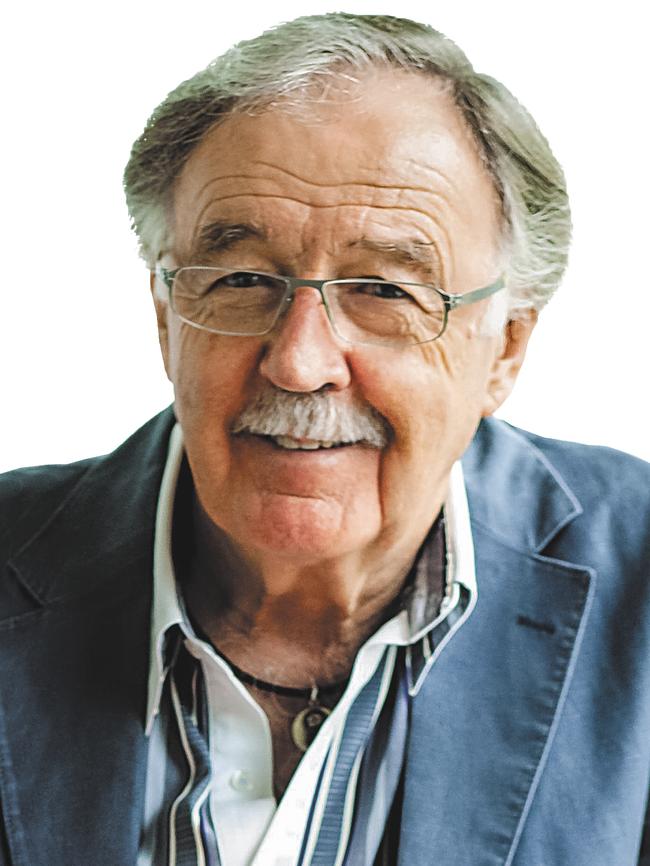

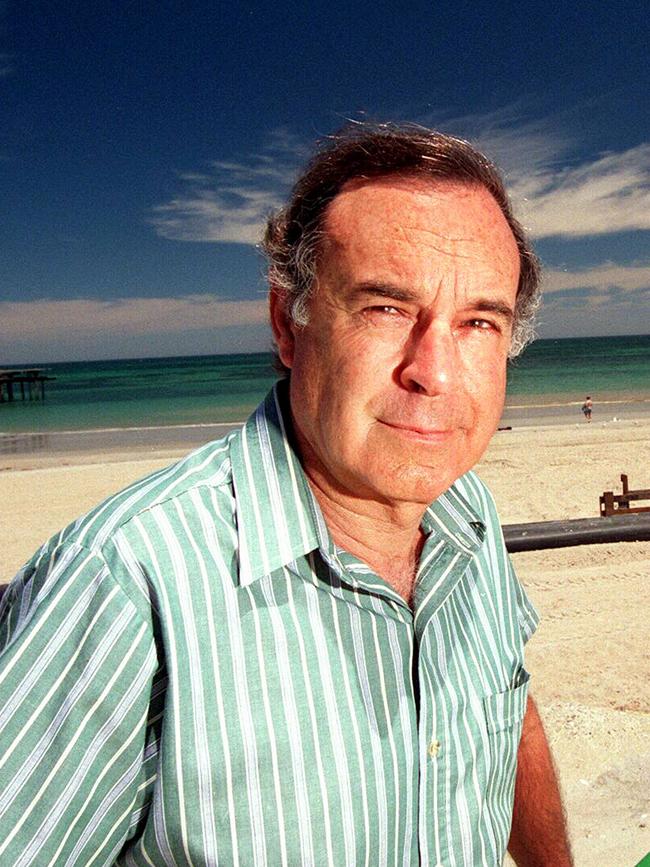

GEORGE NEGUS

(March 13, 1942 – October 15)

Starting as a schoolteacher, he studied journalism and reported for The Australian. He was press secretary for controversial Attorney-General Lionel Murphy and leaked to journalists the impending ASIO raid on his boss’s office. He made his name with the launch of 60 Minutes in 1979. He did the last interview with Libyan dictator Gaddafi, and told Margaret Thatcher people said she was pigheaded. Her legendary response: “Who? And where? And when?”

JUNE MENDOZA

(June 12, 1924-May 15)

Aged 12 she decided to be a painter. At the end of World War II she moved to London studying at St Martin’s School of Art. Gaining international renown, she was commissioned to paint portraits of Queen Elizabeth (five times), Prince Charles, Princess Diana, the Queen Mother, Judi Dench, Joan Sutherland, Sammy Davis Jnr, John Gorton and Margaret Thatcher. She was an AO and MBE and her works hang in London’s National Portrait Gallery.

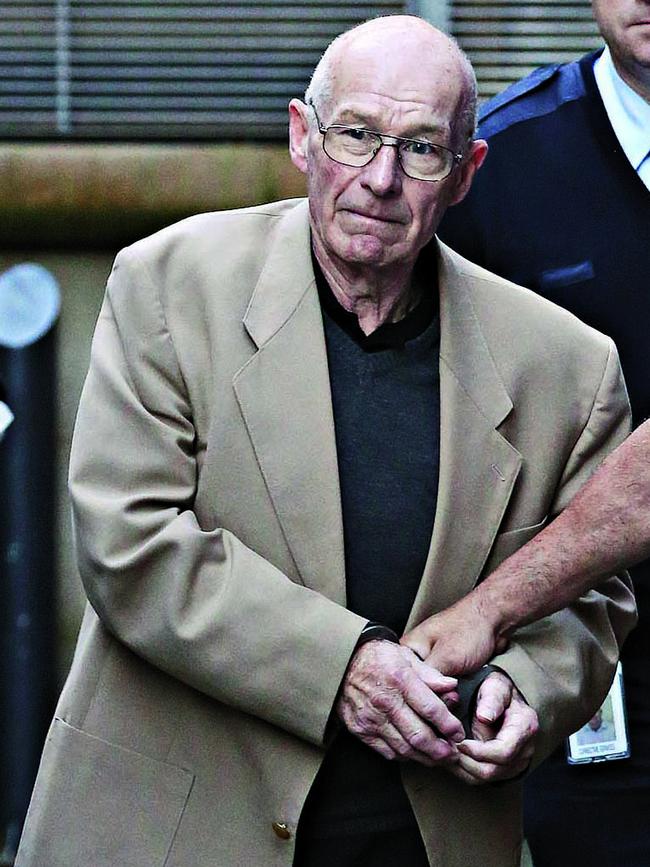

ROGER ROGERSON

(January 3, 1941-January 21)

He was linked to some of Australia’s worst crimes: Brisbane’s Whiskey Au Go Go firebombing that killed 15; Sydney’s Hilton Hotel bombing; the shooting of policeman Michael Drury; the disappearance of hitman Christopher Dale Flannery; the murder of Sallie-Anne Huckstepp whose boyfriend he shot dead; the disappearance of heiress Juanita Nielson; Sydney Luna Park’s ghost train fire that killed seven. He may not have been involved in them all.

MICHAEL LEUNIG

Leunig described himself as “an Australian cartoonist, writer, painter, philosopher and poet” but the Melbourne slaughterman’s son was best known as the first of those. Conscripted for the Vietnam War, he was then rejected because of his total deafness in one ear and found his way via factory work to political cartooning. Sharp as well as whimsical he was sacked by The Age in September, after 55 years, he called the experience “throat-cutting”.

TOM HUGHES

(November 26, 1923 – November 28)

The last survivor of the Gorton-McMahon ministries as attorney-general, he practised law until the month before his 90th birthday. His family included brother Robert, the author. He piloted flying boats in World War II. In 1963, he took on the case of writer Hal Porter who had received a “brief and nasty” review for the book The Watcher on the Cast-Iron Balcony in Hobart’s The Mercury newspaper – and won.

STEELE HALL

(November 30, 1928-June 10)

He defeated Don Dunstan by a single seat to lead South Australia from 1968 and immediately dismantled the gerrymander that had kept his Liberal and Country League colleagues in power for decades. As a result, he was swept from power in 1970. The unlikely reformer advanced Aboriginal affairs and fluoridated the state’s water supplies while building the Chowilla Dam. He served in the Senate and then the House of Representatives for 15 years.

PETER STEEDMAN

(December 7, 1943-July 10)

Failing to complete a calendar year as a federal MP, he left a mark like no other. The larrikin Labor man was cantankerous and courageous. He arrived in Canberra dressed like James Dean on a Vincent motorbike, aged 40 telling reporters he was 28. He edited both Monash and Melbourne University newspapers, was a playwright, wrote for News Corp and helped run Oz magazine while its editors faced the infamous obscenity trial.

MAGGIE SMITH

(December 28, 1934-September 27)

Her Academy Awards explain the breadth of her talent – in 1969 for the drama The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, and seven years later in the Neil Simon comedy California Suite. A Royal Shakespeare Company star, she appeared alongside Whoopi Goldberg in Sister Act, starred in the film version of Graham Greene’s Travels With My Aunt and will be remembered fondly as Professor Minerva McGonagall in the Harry Potter films.

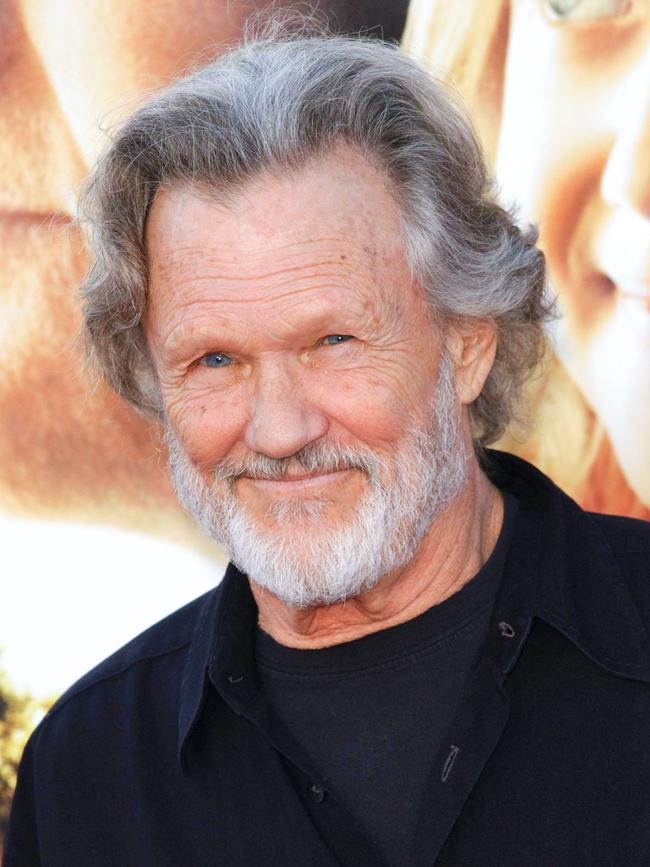

KRIS KRISTOFFERSON

(June 22, 1936-September 28)

While cleaning Columbia Records studios in the 1960s, he wrote songs – Me and Bobby McGee, Help Me Make it Through The Night, For The Good Times. His life had already been remarkable – a Rhodes Scholar to Oxford, an oil rig helicopter pilot. He landed a chopper in Johnny Cash’s front law with some tapes of his music. The obliging Cash could never have known he’d also be a Hollywood icon.

ISMAIL HANIYEH

(January 29, 1962-July 31)

The Hamas chairman ticked off deputy Yahya Sinwar’s brutal massacre in Israel on October 7 last year. No one knows who boldly planted a bomb under his bed before he travelled to Tehran to visit Iran’s new president Masoud Pezeshkian and Hamas’s key banker. Born in a Gaza Strip refugee camp after his Palestinian Arab parents were displaced from their village, he was among the younger founding members of Hamas in 1988.

ETHEL KENNEDY

(April, 11, 1928 – October 10)

She met Robert Kennedy’s sister at college, but he dated her big sister first. She helped with JFK’s first campaign and encouraged her husband to run for President. She was three months’ pregnant with her 11th and last child when he was shot in 1968. She pledged never to remarry and devoted herself to charities. President Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom for “advancing the cause of social justice, human rights … and poverty reduction”.

ORENTHAL JAMES SIMPSON

(July 9, 1947-April10)

Football legend OJ met his first wife at high school. “He was really an awful person then,” she recalled. His contracts were the biggest in US sport. While still playing he appeared in the TV series Dragnet. He acted alongside Lee Marvin and Richard Burton and was to have been James Cameron’s Terminator. Second wife Nicole Brown told a friend “He’s going to kill me – and get away with it”. He was acquitted of murdering her and Ronald Goodman in 1995.