Doctor crisis: taxpayer billions fail to fix rural GP shortages

Rural and regional communities face a critical shortage of doctors despite billions of taxpayer dollars having been spent.

Rural and regional communities face a critical shortage of doctors despite billions of dollars in taxpayer funds having been spent on the problem over more than a decade, as medical graduates shun general practice and seek to become specialists.

The number of training places for rural doctors will fall this year because of a lack of applicants, while country communities around the nation struggle to fill vacancies and medical practices pay tens of thousands of dollars to overseas recruiters to find doctors.

Figures obtained by The Weekend Australian show 1027 medical graduates accepted a governmentfunded GP training position in 2020, a decline of 173 compared with 2015.

Rural Doctors Association of Australia chief executive Peta Rutherford said general practice was struggling to overcome a “declining applicant pool”.

“The government invests about $1.2bn a year on initiatives aimed at getting a better distribution of doctors,” Ms Rutherford said. “It’s a lot of money but we are still missing the mark.”

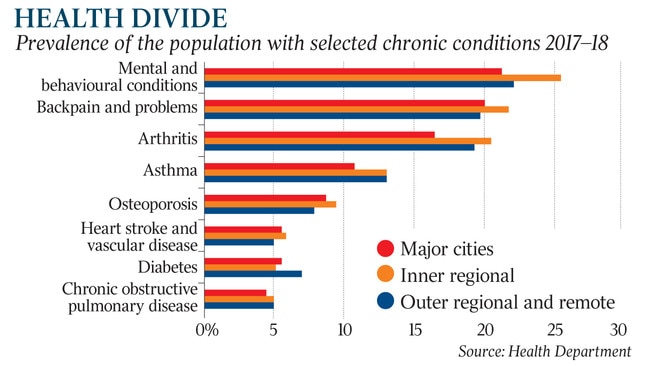

Lack of access to GPs in regional areas compounds the poorer health outcomes already occurring in those communities.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has found the total burden of disease grows with increasing remoteness from big cities. The rate for remote and very remote areas in Australia, measured by “disability-adjusted life years”, was 1.4 times higher than for major cities.

Coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, stroke, suicide, arthritis and asthma all increased with increasing remoteness.

Grattan Institute health economist Stephen Duckett said city-based medical students were given little encouragement to seek a career in regional areas as a GP or otherwise.

“Most city-based medical schools convey to their students that the best career is a subspecialty in a teaching hospital in the city,” Professor Duckett said.

“There is an in-built bias against practice as a rural GP.”

David Gillespie, the Nationals MP for the regional NSW seat of Lyne and a gastroenterologist for three decades, said it was sad to hear that demand for rural GP training places was falling short given the policy attention the issue had attracted.

“For instance, we have a trial going in the Murrumbidgee region that would see GPs looking to specialise being engaged by the local authority, so they would receive leave entitlements like an employee rather than a subcontractor, which would then follow them if they moved their practice,” Dr Gillespie said.

“I think the single employer model will help, and so too would giving more training places to the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine.”

To become GPs, doctors need to complete the Australian General Practice Training Program, and can take a general or rural pathway.

The number of doctors who will begin GP training as part of this year’s RACGP, is 1302, a decline of about 305 since 2015.

The number of doctors who started rural GP training with the RACGP was 609 in 2018. This fell to 486 in 2020, but recovered slightly to 564 this year.

According to the RACGP, the government also allocated fewer positions to the institution’s rural pathway in 2021, with this year’s maximum intake dropping by 48 places to 635.

RACGP rural chairman Michael Clements said the number of doctors being graduated was increasing but “they are choosing a non-GP speciality’’.

This was having a significant impact in the bush.

“It’s not sustained or systemic, but go to any country town and the job pages are full of GPs seeking support,” Dr Clements said.

“There is a lack of investment in general practice by the federal government.”

Deloitte Access Economics estimates the nation is facing a shortfall of nearly 9300 full-time GPs by 2030, representing about a quarter of the workforce, with shortages most acute in the Northern Territory.

In 2020, the Territory had 94 GPs per 100,000 people, compared with the national average of 117.7 and Queensland’s rate of 125.4.

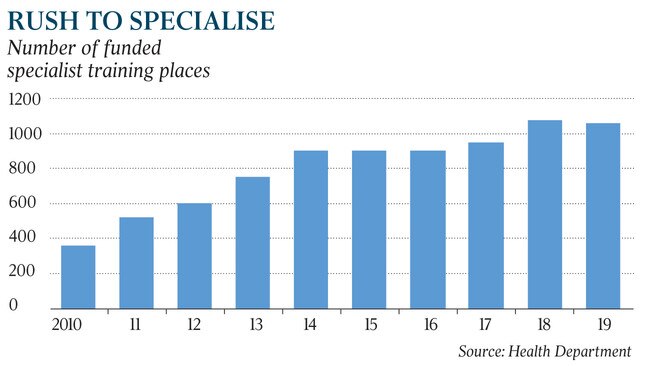

While the number of GP trainee positions offered through the RACGP, including commonwealth-funded and overseas-trained doctors, has fallen, Health Department data shows that training places in other specialties have exploded from 360 in 2010 to 1057 in 2019.

Overseas-trained doctors account for half of the GP workforce in rural Australia.

Billions of taxpayer dollars have been spent to address the shortage in rural GPs, starting more than 15 years ago when the Howard government responded to the shortages in regional and remote areas by boosting medical student numbers and setting up rural clinical schools and regional medical schools. It also increased admission of rural students into medical schools.

A spokesman for Health Minister Greg Hunt said the government committed $550m in the 2018-19 budget in an effort to attract doctors to rural and remote Australia.

“After the first two years, more than 800 additional GPs and 700 additional nurses are working in regional and remote areas,” the spokesman said. “Since 2013, the number of GPs in Australia has been growing at 2½ times the rate of the population.”

But those moves have not placated the medical community, which remains concerned that Australia is playing “catch up” after neglecting the needs of general practice for too long.

Lesleyanne Hawthorne, a professor at Melbourne University’s centre for health policy, said Australia had set the goal of medical self-sufficiency more than a decade ago.

“But we’ve still got a chronic problem,” Professor Hawthorne said. “We had 1140 permanent slots for overseas doctors to June 30, 2019, but immigration doesn’t tell us where they are going.”

As part of the 2020-21 Visas for GPs program, the health department directed 66 per cent of overseas trained doctors or those who renewed temporary visas to non-metropolitan areas.

National Rural Health Commissioner Ruth Stewart said the medical profession had embraced sub-specialisation at the expense of general practice.

“We are facing a by-product of a medical training system that believed quality equalled specialisation,” Dr Stewart said.

“If you look at the outcomes of sub-specialised service, it is not safer than a generalist and does not actually improve a community’s health outcomes.”