Coronavirus: loneliness, sadness and despair are very real dangers of long-term self-isolation

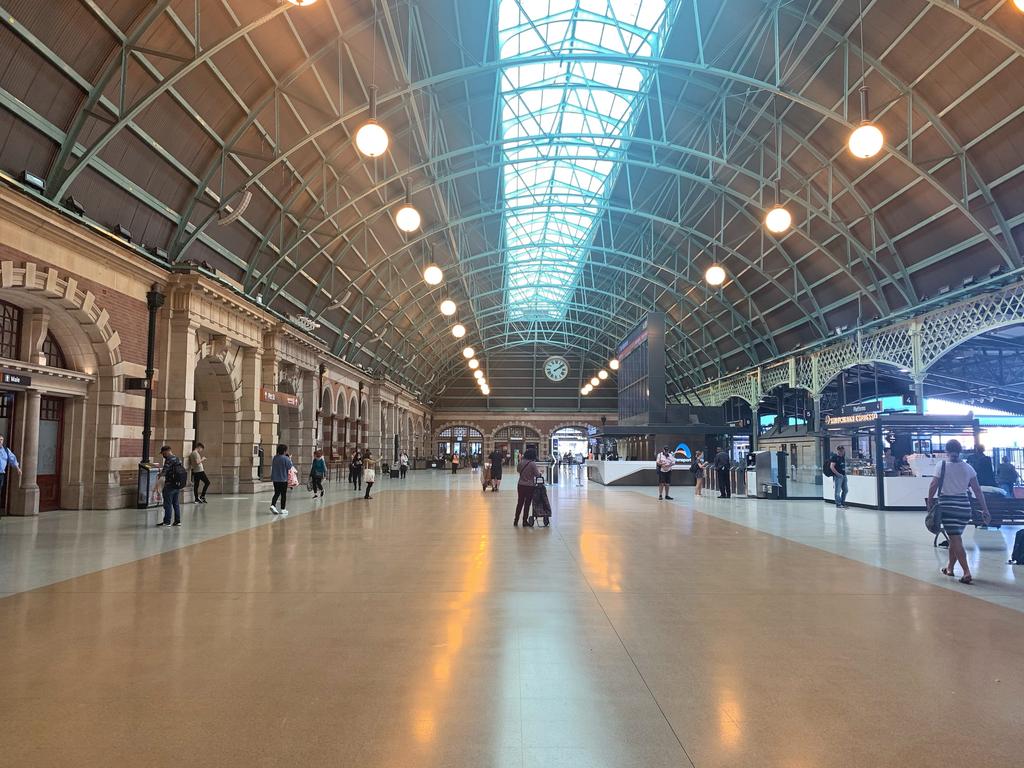

Australia could go one of two ways as the new normal of social isolation drags on from days, to weeks, to six months, or longer.

Australia could go one of two ways as the new normal of social isolation drags on from days, to weeks, to six months, or longer.

We could embrace the experience, finding ways to deepen our intimate relationships as we spend more time at home and manage our broader work and social lives via a deeper connection with technology. Or we could turn psychologically inward, struggling with loneliness and sadness as we stay indoors and hide from potential infection, occasionally scuttling out for supplies in a Hunger Games battle for survival.

As with almost everything in the coronavirus global pandemic, which of these scenarios plays out in the national psyche is still unclear. Experts have different views, but they agree on one thing. This will be a long haul.

The growing consensus, confirmed by Scott Morrison on Wednesday, is that social distancing measures — restricted gatherings, children’s and social sport cancelled, cultural venues shut — are likely to be in place for at least six months. Until September. Or perhaps even later.

This is a fundamental societal shift that runs counter to the human desire for connection. Feel-good social media moments like the aerobics class taken by an instructor on a Spanish rooftop for people in surrounding apartments is little more than a short-lived sugar hit against the looming, long and prevailing unease.

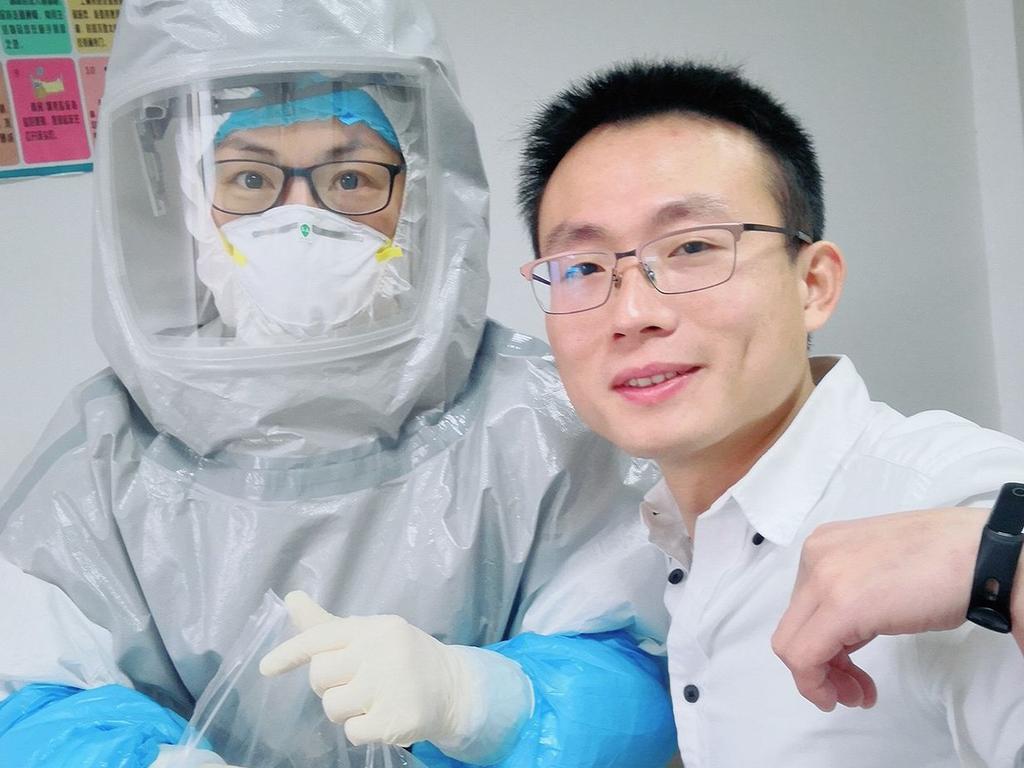

Relationships Australia national executive officer Nick Tebbey said the very nature of the COVID-19 pandemic created a different dynamic to previous social upheavals. “In the recent past, natural disasters have tended to bring people together, but the nature of this one is to force people apart, physically at least,” he said.

“It would be remiss to think people aren’t going to struggle psychologically to adapt to a situation that forces them away from basic human interactions.”

But he senses that the longer the restrictions last, the more the community will come to accept the changes.

“We’ve seen a fair bit of uncertainty so far. That will recede I think and people will settle into the new arrangements. Research and experience show Australian communities are good at banding together.”

Michelle Lim, a clinical psychologist and scientific chair of the Australian Coalition to End Loneliness, is not so sure. She said the response to social distancing would vary according to household type, available resources and individual personality.

“When we are cooped up, we don’t all react the same way,” she said. “For a lot of people with high social needs, extroverts and those with active social lives, they will start to feel disconnected, and if this goes on for a long time, they will feel increasing stress.”

Dr Lim is also unsure how the new stay-at-home work regime will play out in the emotional lives of Australians.

“Remote working sounds ideal for a month or so, but we really won’t know how it affects people over the longer term, for six months or more, if your only interactions are with your own household and your neighbours,” she said.

Almost one in four households in Australia is a single-person household, according to the most recent Census, but Dr Lim said there were plenty of people living alone who weren’t lonely, and lots of people living with their families who were.

Her research has shown that people who live alone are often quite adept at taking care of their social health, and the ones who may struggle might be couples who don’t regularly spend long periods of time together.

“Some people need more space. Others don’t care. The prolonged nature of this means we are going to have to work out ways to navigate relations in the household, finding our own space and time,” she said.

The Melbourne Institute’s Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey looks at loneliness in Australia. It has found that, before the coronavirus, 18 per cent of people already said they were often lonely.

HILDA deputy director Roger Wilkins suspects the new social distancing arrangements will likely create initial anxiety, which over a longer period could increase to, if not greater loneliness, then “a general sense of sadness”.

“Life just won’t be feeling as good. There just won’t be the things people are used to looking forward to — travel, sport, cultural activities,” Professor Wilkins said.

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists president John Allan said there would be pockets of Australian society who would feel the social distancing measures most keenly, in particular those at the margins who are already lacking social contact. “I think of the homeless, those in inadequate housing, those people with disability who may lose supports and have difficulty changing their routines,” Associate Professor Allan said.

“And given that more people might be spending more time at home, there may also be adverse consequences for those at risk of domestic violence,” he said.

Technology is being hailed as the communications saviour while we are isolated from each other, but there are issues with that. Older people, the group at most threat from the virus, often struggle with using social media platforms to stay connected.

“According to our research, 57 per cent of Australians aged 70 and older have low to no digital literacy,” eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant said. “Among those over 50, 62 per cent have never made a video call and 58 per cent have never chatted online. It could mean teaching them how to make a video call or shop online.”

Mr Tebbey said it was important to care for them. “Pick up the phone to your elderly neighbour. Ask them how they’re doing. Bake an extra batch of muffins for them,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout