Bureau’s dry summer prediction drowned out by above average rainfall

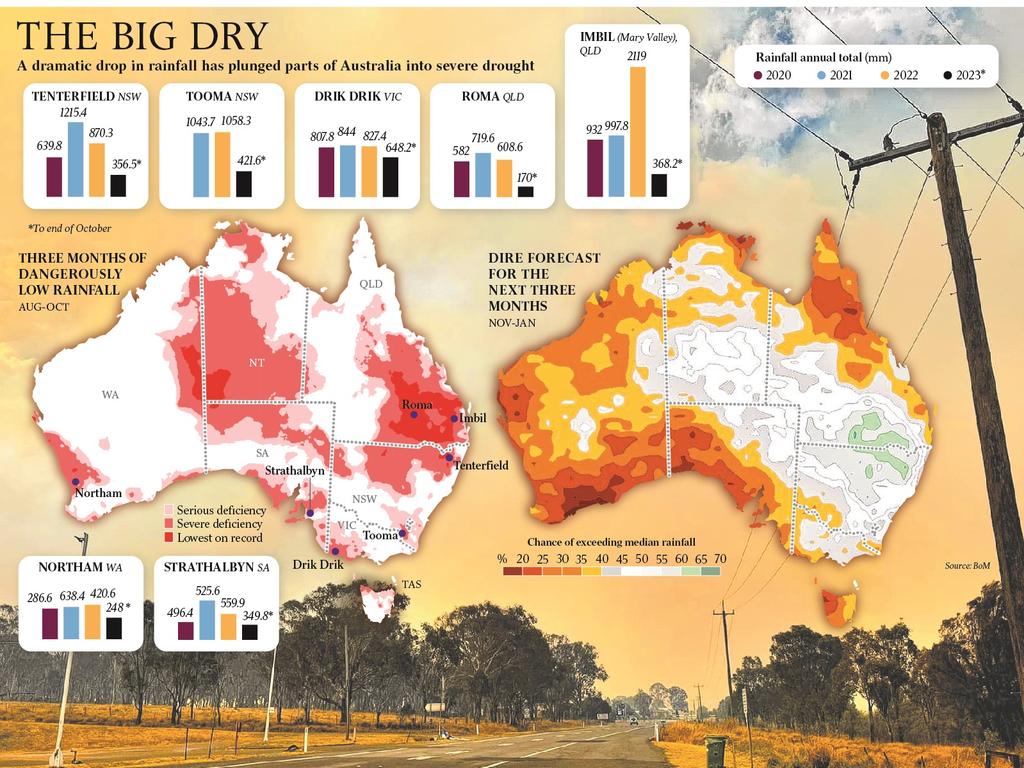

Rainfall percentages for the past three months across eastern and northern Australia show a stunningly different scenario to what the Bureau of Meteorology forecast in its summer outlook.

The weather bureau’s forecast for a dry summer has proved remarkably wrong, with two thirds of the continent receiving higher than average rainfall.

Rainfall percentages for the past three months across eastern and northern Australia show a stunningly different scenario to what the Bureau of Meteorology forecast in its summer outlook.

The bureau’s warning in September that the El Nino climate driver was in effect left Australians bracing for a hot and dry spring and summer.

It was partly blamed by some farmers for spooking producers into selling livestock, leading to a flooded market that sent sheep and cattle prices tumbling.

The forecaster was also criticised for failing to predict the deluge that led to major flooding in far north Queensland after Cyclone Jasper in December.

Meteorologists and the government have defended the organisation, saying outlooks were complicated but increasingly accurate over time.

But analysis of rainfall data released by the bureau shows stark difference between what was forecast and what happened.

The bureau’s summer outlook predicted below average rainfall for “much of the tropics and Western Australia, and a more neutral rainfall signal for the rest of the continent”.

In reality, while summer was the third warmest on record, most of eastern Australia recorded above average summer rain.

“For Australia as a whole, the area-averaged rainfall total was 18.9 per cent above the 1961–1990 average for summer,” the bureau said in its seasonal summary on Friday.

“Rainfall totals were above average for the Northern Territory and all states except Western Australia and Tasmania.

“Summer rainfall was above average for large parts of the eastern two-thirds of the mainland, with areas of very much above average (in the highest 10 per cent of all summers since 1900) scattered across Queensland, New South Wales, northern parts of the Northern Territory, Victoria and southern South Australia. Some stations in these areas had their record highest total precipitation for summer.”

Gerard Glover, who runs sheep and cattle near Brewarrina, 380km northwest of Dubbo, was glad the bureau’s outlook did not match reality.

When The Australian visited his property in early December, paddocks of bare dirt reflected a dry spring and depleted pastures forced him to consider destocking into a rock-bottom market.

But late December rain and a wetter than average January brought new growth and fresh hope.

“We were thinking we were going into a dry spell but that December rain alleviated a few things, gave us a little bit of water and a little hope, but the rain in January was very welcomed,” Mr Glover said.

“We probably hung on for too long with our stock last year, but it’s turned out ok. The markets have steadied a bit now.”

Cattle prices in the eastern states have almost doubled since September and lamb values have risen by about 50 per cent.

Mr Glover said many farmers relied on their own historical rain charts to identify current patterns to supplement the bureau’s forecasts.

“I listen to the bureau and watch what they talk about but I only look about a week in advance, because after that they get a bit wobbly in the knees,” he said.

“Generally, on a daily basis, if they say you’re going to get 5mm, you’ll get 5mm, but anything beyond 10 days out often doesn’t eventuate.”

Professor Janette Lindesay from the Australian National University said no two El Nino events were the same and that the multiple drivers affecting Australian weather made long-range forecasting difficult.

“We’ve had a whole lot of things interacting with each other, as these drivers do,” Dr Lindesay said.

“We can’t assume that just because there’s an El Nino event, whether it’s weak, medium or strong, that’s it’s going to be particularly dry at a particular time in a particular place.”

Dr Lindesay said dominant climate drivers only accounted for a portion of rainfall.

“In summer, for instance, there is only a maximum of about 15 to 25 per cent of rainfall variability accounted for by any of the climate drivers,” she said.

“We have to bear in mind that there is a lot more going on.

“That means that even if we had a strong El Nino event, and everything is perfect with that, and there’s an Indian Ocean Dipole positive event reinforcing that, it doesn’t necessarily mean it will result in below average rainfall because there is a whole lot more at play.

“75 per cent of summer rainfall is coming from other things.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout