The house that Getty built

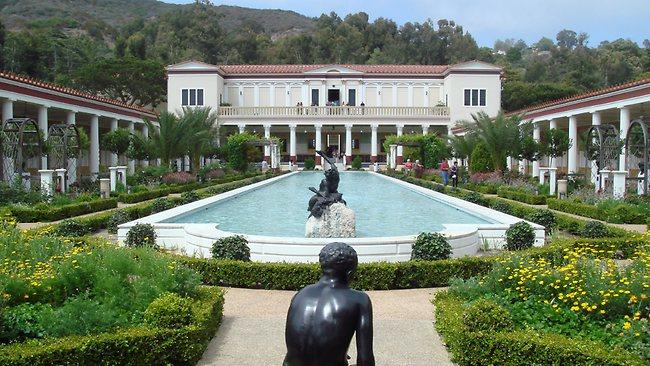

ANCIENT Herculaneum is replicated in Malibu, in the shape of a villa housing priceless Greek, Roman and Etruscan antiquities.

MALIBU Beach is not the only place in northern California famed for its magnificent bronze bodies.

Rising above the Pacific coast is one of the world's premier museums of antique art: the John Paul Getty villa. And among the 44,000 antiquities in the Getty collection, one of the loveliest, in the opinion of senior curator Claire Lyons, is a 1st century AD bronze nude of a lithesome youth, or ephebe.

"It's a really wonderful piece that was excavated from a house in Pompeii," she explains. "He's a lamp-bearer and holds a beautiful candelabrum. He endured the eruption of Vesuvius in 79AD remarkably well and was found still standing in what has become known as the House of the Ephebe."

The young lamp-bearer is displayed in a special niche in the gallery and his undoubted beauty and rarity - few bronzes have survived from the ancient world - are two good reasons he enjoys pride of place there. Another is his provenance, or back-story, as a survivor of the cataclysm to which the villa itself is connected. And thereby hangs quite a tale.

When oil magnate J P Getty decided to house his private collection of art and antiquities in a public setting he turned for inspiration to the ruined Vesuvian landscape, which he had visited on his Mediterranean travels. For it was there, just outside the dead city of ancient Herculaneum, that 18th-century antiquities hunters had discovered the remains of a Roman seaside villa housing exquisite bronzes and an unparalleled library of papyrus scrolls.

Tunnelling through metres of petrified volcanic mud, excavators were able to fish out the villa's treasures, many of which now grace the Naples National Archaeological Museum. But the mansion itself, in its day a place of luxury, connoisseurship and learning, has never been entirely disinterred and most of it lies buried on the outskirts of Herculaneum. Thanks to an industrious engineer from that first excavation, however, a ground plan of the villa survives and it was to this that Getty's consultant, historian Norman Neuerberg, and his architect Stephen Garrett, turned for inspiration. Construction of the Getty Villa began in 1970 and took four years. The end result is not so much a Disney-like fantasia as an act of homage, says Lyons. The Getty Villa in Malibu is a more or less faithful rendering of the Villa of the Papyri, as it has come to be known, with the addition of decorations, walls, pavements and other features inspired by Roman domestic architecture of the region.

"In the time it was constructed, the mid '70s, a time of modernism, the idea of historical reconstruction at first was received ironically," Lyons says. "But, over the years, people have come to appreciate how a visitor here can understand and experience the spaces of an elite Roman villa as well as the relationship of the interior to the garden, and to see works of ancient art in a relatively accurate setting. The site on the coast of Malibu echoes the coast of Herculaneum and I think it's really an ideal way to appreciate ancient Greek, Roman and Etruscan art."

The Getty Villa housed the entire Getty collection until 1997. In that year the collection of European paintings, drawings, sculpture, illuminated manuscripts, decorative arts, and European and American photographs, which had grown under the purchasing power of the Getty trustee's $US5 billion endowment, moved to the new Getty Centre in Los Angeles. The villa underwent a restoration and reconfiguration at the hands of Boston architects Machado and Silvetti, and was unveiled to the public in 2005. It had been given a new entrance with echoes of the approach to the Villa of the Papyri, buried as it is under layers of volcanic concrete, a 450-seat outdoor classical theatre and a cafe, as well as more than 50 new windows to help illuminate the displays.

Whether one views the result as a work of art in its own right, as a piece of extreme retro, pastiche or antique kitsch - or perhaps some combination of all four - there is no doubting the quality of the collection housed within the villa. Aside from the young lamp-bearer, Lyons lists among her "must-sees" the Lansdowne Heracles, a Roman statue first discovered in 1790 at the site of Hadrian's villa in Tivoli that was a favourite of Getty's, who bought the statue from the British Lansdowne estate in the 1950s.

"One of the reasons I'm interested in this statue is that my research has often been on the afterlife of antiquity, or the role that ancient art and culture played in the shaping of the Renaissance and the centuries that followed," Lyons says. "So objects that have a long biography, that have different meanings in the Roman period, the Renaissance, the 18th century and right up to the present, can be looked at in so many different ways. They are mirrors of ancient culture and our culture."

Among "many loveable objects" she also notes a "particularly special and unique group of pottery" called the Orpheus group, which features the musician Orpheus together with the Sirens, mythological females with the bodies of birds whose song was so sweet that they lured sailors to their deaths. The hero Odysseus was, famously, privileged to hear their chant after he had himself chained to a mast and had his crew's ears stopped up with wax. "To see groups of musicians accompanied by singing sirens on a large scale is something that is absolutely remarkable," she says.

Recent interest in classical civilisation flagged by a slew of books and films anchored in mythology and classical history, as well as exhibitions such as the Pompeii show that recently toured a number of American museums and the National Gallery of Victoria, leads Lyons to dismiss talk of a renewal of interest in antiquity in favour of a "perpetual interest". A practising archaeologist, she is a scholar with an interest in the reception of antiquity - in the ways the deep past has been used to shape the present.

"On the one hand we know an enormous amount about the ancient world, including daily life, but so many aspects are missing," she says. "So one attempts to reconstruct those gaps based on what we do know, based on the literature we do have. But it's clear that every generation looks to antiquity and sees its reflection there and finds its own meaning. That's one of the reasons it's so present. It's ever meaningful. It's ever forceful and ever useful. That is what culture is: a continual process of interpretation and re-use. That's human."

Neoclassicism, of which the Getty Villa is a late example, has played a prominent role in the public architecture of the US, and its stamp can be seen everywhere from Washington Square in New York to the Lincoln Memorial. One school of thought sees this as similar to the attraction felt in the new Rome towards the symbolism of the old Imperium: as a power thing. But Lyons believes the memory of Republican rather than imperial Rome holds the key. She notes the way architectural forms of classical antiquity had been part of the European architectural "vocabulary" since the Renaissance. "It was only natural that the founders of the US, many of them classically trained, should also turn to these models for institutions of government, the law and business. It was in part an attraction to the Republicanism of ancient Rome and in part to ancient Greece as the seat of democracy."

Among the collection's 44,000 pieces, only 1200 of which are on display at any one time, there are also many works of erotica, in keeping with the Roman taste for explicit sexuality. For a resident of 1st century Pompeii, however, a wall fresco of a figure with an outsized penis was more a fertility or good luck charm than an object of arousal.

Unlike bustling and commercial Pompeii, ancient Herculaneum was an aristocratic seaside residence. "It was a place to pursue otium, or refined pleasure," says Lyons, "in contrast to the business of city life, which the Romans called negotium." The Getty Villa experience offers something along similar lines. "It's a lovely space, somewhat separate from Los Angeles," Lyons says, "especially if you're travelling in time back to the Bay of Naples. It's peaceful. It's green. You can sit outside, have a delightful lunch overlooking the ocean and see some art."

Not all is becalmed at the Getty Villa, though. Since Italian courts indicted the Getty Museum's former curator of antiquities Marion True on charges relating to international traffic in illicit antiquities, the villa has repatriated a number of its prize works to galleries in the old world. Lyons believes the scandal has helped the Getty, as well as many other museums, to develop more explicit guidelines regarding the antiquities trade. "We have a cultural agreement with Italy and have signed with Greece just recently," she says.

On the most controversial of all acquired antiquities - the debate over the return of the Parthenon Marbles - she is diplomatic. "The new museum in Athens is absolutely inspiring, with its sight line to the ancient Parthenon," she says. "But so, too, is the British Museum with people from around the world drinking in these beautiful works. Should the Parthenon frieze stay in London or should it be returned to Athens? It's a genuine quandary. I can feel thrilled in both places."