Kenton Cool took over Everest – and you can too. For a price.

The Brit has summited the world’s highest peak 18 times, and for $500,000, he’ll take you up with him.

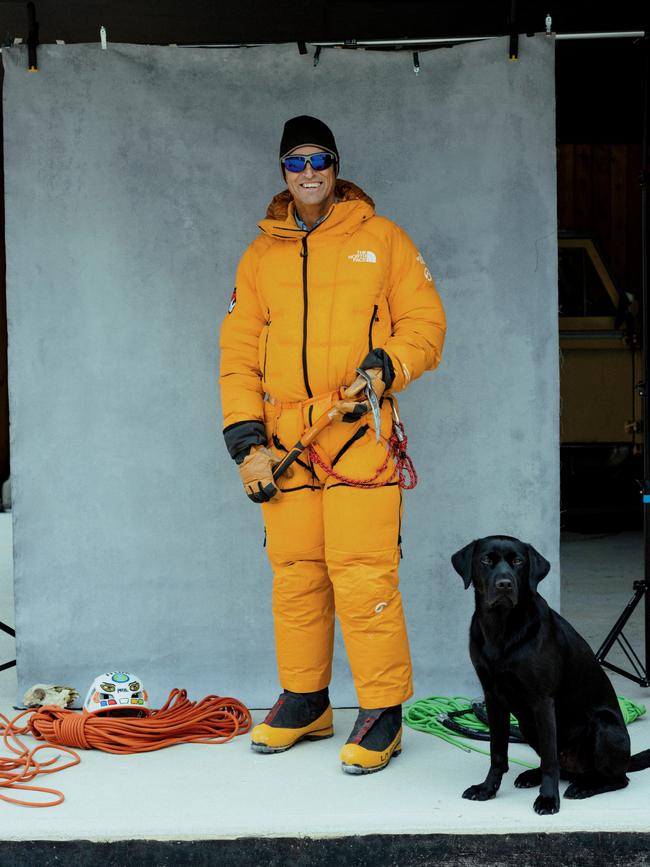

Fresh from the Himalayas, Brit Kenton Cool stands in his garage in the British Cotswolds stowing away climbing gear: a bright yellow down onesie with his name patched on one of the arms, various coiled ropes, his helmet. That helmet has been painted with blue, white, red, green, yellow – the colours of Nepalese prayer flags – and the eyes of Buddha. “They’re all-seeing,” he says.

He has done his daily 10-kilometre run and seems relaxed and happy – with good reason. On May 12, 2024, the wiry 51-year- old climber and high-altitude mountain guide broke his own record, having reached the top of Mount Everest for the 18th time, more than any other non-Nepalese person. “A friend sent me a message saying, ‘You may have to see a therapist about your Everest addiction’,” Cool says with a grin.

He has become a rock star of the mountaineering world, taking the non-Nepalese Everest crown in 2022 from Dave Hahn, an American who reached the summit for the 15th time in and then retired from the mountain. Nepalese Kami Rita Sherpa has the most notches on his ice axe with 29 summits to his name.

Cool made his latest trek to the top of the 8849-metre (29,032 feet) peak as the hired guide of London businessmen Graham and Chris Parrot. “They’re the first British twins to reach the summit,” he says in the kitchen in his glass-fronted home, a converted piggery in Gloucestershire, where he lives with his wife, Jazz, a personal coach, and their children, Saffron, 14, and Willoughby, 11.

“When I came back from Nepal, I sat outside with my wife having a cup of tea and said, ‘I think that just cements it. I’m the most successful Everest guide there has ever been’. Not that I’m crowing from the rooftops. I don’t do that.”

Cool, whose name was anglicised from Kuhle by his half-German grandfather during World War II, is one of a dynamic cast of characters helping businessmen, celebrities and other high-paying thrillseekers get to the planet’s highest point. He charges up to $500,000. “If it wasn’t my job, I wouldn’t want to climb Everest every year,” he says. But it does help pay the school fees: Saffron is at Marlborough College [alma mater of Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge]; Willoughby at nearby Hatherop Castle School.

Much as guiding is also his passion, Cool sometimes wonders how much longer he can do it. “I’m not getting any younger,” he reflects at the kitchen island, a vast slab of marble. Horror of horrors, this year’s clients, the Parrots, in their mid-thirties, were fitter than him – a first. “That’s a worry,” he admits while Otis, his black labrador, sits peering up at him, tail drumming on the floor.

Another issue is how sustainable the industry is. For some critics, the trophy baggers have turned Everest into a litter and body-strewn dump. They believe it is now less a mountaineering challenge than a polluted extreme-tourism resort made all the more hazardous by overcrowding, greedy adventure companies and climbers with big bank balances but little climbing experience. Allegations of sexual assault of female clients and sherpa exploitation have added to the dark cloud hanging over the mountain along with tales of a new breed of climbers trooping past people dying of oxygen starvation near the summit without stopping to help.

For the Nepalese government, which charges thousands of dollars for a licence to climb the mountain, the growing business is a windfall. “I don’t think they will limit the number of climbers,” Cool predicts. “It’s a cash cow for them, not just from the permits but also the trickle-down for hotels and porters.”

This brings to mind the now famous photograph taken on May 22, 2019, which showed a crammed conga line of climbers queuing to reach the summit in bright sunshine. During a brief window of good weather that season about 500 climbers reached the top but 10 died trying. Cool believes Everest can manage the multitude. “If the industry is sensible, numbers should be workable.”

Nor does he sound overly worried about a once pristine environment being poisoned by rubbish and helicopter traffic ferrying VIP clients on and off the slopes. “Yes, it does have an impact on the mountain, but if we had one year off from climbing Everest it would quickly bounce back, so I don’t have any long-term fears for it. Most operators are conscious about the footprints of their expeditions. I think we are in a relatively good place.”

For detractors, the mountain named in 1865 after George Everest, a British surveyor, has become a circus: the main base camp on the Nepalese side, a mile-long warren of high-spec domed tents, now offers every luxury to climbers as they acclimatise for their trek to the top of the world. The best accommodation comes with Tibetan carpets, padded lavatory seats and solar-powered showers. The highest-paying climbers can also expect fast internet and fresh coffee and croissants for breakfast. They can attend art exhibitions, gin and tonic happy hours or rock-climbing classes. One company, Seven Summit Treks, has a $300,000 VVIP package where clients waiting for a window in the weather are whisked away from base camp by helicopter for some mid-expedition R&R in a Kathmandu spa hotel. For years old-school purists have been decrying the trend. “It’s becoming so you can go to the beach for your holiday or climb Everest,” said Edmund Hillary, the New Zealander who became the first climber, with Tenzing Norgay Sherpa, to reach the summit in 1953. “Sitting around in a big base camp, knocking back cans of beer, I don’t particularly regard as mountaineering.”

Yvon Chouinard, the 85-year-old founder of the Patagonia outdoor clothing company, has a blunt view of even using guides to get to the top. “If you compromise the process that much, you’re an asshole when you start out and you’re still an asshole when you come back,” he is quoted as saying in Everest, Inc., a brilliant new book by Will Cockrell about the “renegades and rogues who built an industry at the top of the world”.

The book notes that, in the four decades after Hillary’s ascent, only 394 people reached the summit. When guides began taking paying customers up the mountain in 1992 it opened the floodgates. Some 11,500 people have reached the top since then.

Cockrell points out that the mountain’s safety record is actually pretty good. The percentage of deaths to successful attempts is just 2.7 per cent compared with 23 deaths per 100 successful summits for K2, the world’s second highest and much more difficult mountain, in Pakistan.

Some claim it is no longer a true climbing challenge, merely a very difficult walk. Indeed, few technical climbing skills are required, with the roped route set by teams of sherpas at the start of each season. The infamous Hillary Step, a 12-metre-high near-vertical section of rock just 60 metres below the summit was once considered the technically challenging crux of the last push, but it collapsed after an earthquake in 2015 and is now just “an easy set of giant stairs”, according to Cockrell. As 89-year-old British mountaineer Chris Bonington puts it: “You don’t really need much climbing experience on Everest”.

Though not a technical climb like K2, that doesn’t mean Everest is a walk in the park. An expedition typically lasts from six to nine weeks. After reaching base camp at 5364 metres, several weeks are spent making return trips to the higher camps to move equipment and acclimatise. The final ascent to the summit can take about five or six days. It typically takes two to three days to descend back to base camp.

Any mountain above 8000 metres involves navigating the death zone, where there is not enough oxygen to sustain human life for long. Camp 4, where climbers often sleep before and after the summit, is at 8000 metres. “The deterioration of the body is pretty rapid,” says Peter Hackett in Everest, Inc., an American expert in high-altitude physiology. “‘Wasting away’ is another good term. Or ‘dying’.”

The 2023 Everest climbing season, when Cool guided Richard Walker, the chairman of Iceland Foods, to the summit, was the deadliest on record in absolute terms, with 18 climbers lost. In 2024 five climbers died and three went missing, including a British climber, Daniel Paul Paterson, 40, and his 23- year-old guide, Pas Tenji Sherpa, who disappeared on May 21 after reaching the summit. They join the more than 200 bodies thought to lie on the mountain.

One of those bodies belongs to the German climber Hannelore Schmatz, who was making her descent from the summit in 1979 when she sat down exhausted in the snow and never got up. “Her frozen body sat in its final resting place for nearly 20 years, her eyes wide open and dark hair eerily blowing in the wind for passing climbers to see on their way to the summit before she was finally extricated from the ice, either by unknown climbers or the elements,” Cockrell writes in Everest, Inc..

The latest body to be found was that of Cheruiyot Kirui, a Kenyan climber who went missing in May 2024. Because of the difficulties involved in bringing the bodies down, the majority of the dead are left on the mountain. “The bodies reinforce the heroism of climbing Everest as the stakes are literally staring you in the face,” says Heather McDonald, an American guide.

“You see bodies every year, new ones and old ones,” Cool says. “We saw three this year. The highest one is from 2019. He’s stuck on the rope. I’m surprised somebody hasn’t cut him loose. You almost end up standing on his head to get past him. It’s quite an awkward situation, quite graphic. Not very nice at all.”

While climbing in 2022 Cool forgot to forewarn his client Rebecca Louise Smith, a California-based fitness influencer, who “came merrily round the corner and face-to-face with this body. She got quite a shock”.

The remains of George Mallory, the British climber who disappeared on the northeast ridge in 1924, were discovered only after a search effort in 1999, although recent reports claim his corpse has mysteriously disappeared.

One of the most famous corpses is “Green Boots”, believed to be Tsewang Paljor, an Indian climber who died along with seven others when a blizzard engulfed the summit in 1996, a disaster recounted by the American journalist Jon Krakauer in his book Into Thin Air. “His boots have faded in the sun,” Cool says. “He’s used almost as a waymarker. ‘Are you past old Green Boots yet?’ Which is a little macabre, but people are getting security from knowing that they can report where they are. So even in his demise that individual is giving back to the community.”

In 2006 David Sharp, a 34-year-old Englishman, took shelter in the rocky overhang next to Green Boots and succumbed to the elements. According to Nick Heil, an American journalist who was on the mountain that year, as many as 40 climbers may have passed him without offering to help. It’s an ethical quandary that dogs high-altitude mountaineering.

Cool says he would try to “do the right thing” in such a situation while bearing in mind his “first responsibility”: the safety of his clients. He once encountered an unconscious climber high in the death zone of Lhotse, Everest’s neighbour, the world’s fourth-highest mountain. As dusk fell and the temperature plummeted, he shared his oxygen with the man instead of continuing his descent, staying by his side throughout the night. “He passed away in my arms,” Cool says. “It was shocking.”

Cool has proved his remarkable resilience in the death zone not only by climbing but also skiing down some of the world’s highest Himalayan mountain slopes. He thinks an ability to engage in physical activity in an oxygen-light environment has more to do with mental strength than living at high altitude or being able to produce extra blood cells. “I was born in Slough,” he says with a chuckle about his home town, a mere 33-metres above sea level. “I don’t mind suffering, I don’t mind holding my head in my hands and going, ‘This is hard’.”

His father was a photographer, his mother a florist. His first climbing experience was with the Boy Scouts in Wales. It soon became his passion. Having graduated in geological sciences at Leeds University, he fell from a rock face in north Wales in 1996. “I did a proper job of smashing myself up,” he says. “I broke my heel bones. I pulverised both of them. I was told I wouldn’t walk without a stick, that I certainly wouldn’t be able to run or climb.” He proved the doctors wrong but his feet still hurt him at times. “I’ve got metal plates and pins in there.”

Cool’s climbing career took off in 2004 when he was offered a job on Everest as an expedition guide by Simon Lowe of the trekking company Jagged Globe. When another expedition leader dropped out, he was promoted to lead guide. “I loved it and kept going back,” he says. His renown grew in 2006 when he became the first Briton to ski down an 8000-metre mountain: Cho Oyu in Nepal, the sixth highest in the world. In 2008 he guided the explorer Ranulph Fiennes up Everest, turning back 300 metres from the summit. They were luckier the following year when, at 65, Fiennes, became the oldest Brit to reach the top. “He went like a steam train that year. I could hardly keep up with him,” Cool recalls.

Cool, of course, has a podcast, Cool Conversations, and a gig as a motivational speaker. He does not advertise his services as a guide. “It’s generally word of mouth,” he says. “A lot of my clients come out of the City [in London], for want of a better word. When you’re at that level, it’s a fairly small circle.”

He likes to meet prospective customers over a glass of wine or a coffee before deciding whether to take them on. If that goes well, he will propose a climb in the [French] Alps. Is this a chance to assess their climbing skills? “More than that,” he says. “I want to see how we get on. I want to see what the relationship is going to be like. If you push someone in those first three or four days, if they’re tired, or thirsty or hungry, you get to see most of their character traits. So, you push them a little bit. But you don’t want to break them, to make them totally miserable.”

He will never forget one job interview with a potential client from America. “We had lunch and I was outlining how the next two years might work. Maybe we would go to the Alps, maybe to Bolivia, Nepal, do a 6000-metre mountain. He stopped me right there and said, ‘I don’t think you understand. I want Everest to be the first and only mountain I ever climb’.” Cool turned the job down.

Some of his fellow climbers suspect he guides his rich clients primarily to finance his Everest “addiction”, not to help others to the top. He denies it. “As my power to do my own climbing starts to diminish, I get a greater rate of joy out of helping my clients to fulfil their ambition.” He adds: “My love of the mountain prevails whether

I am climbing for myself or guiding a client. I do get equal joy out of both.”

The ringmasters of Everest’s sometimes deadly circus – the guiding company impresarios and Everest entrepreneurs – are generally a colourful bunch. Besides a reputation for supplying cut-price oxygen cylinders, Henry Todd, a 79-year-old Scottish mountaineer and the founder of Himalayan Guides, spent seven and a half years in prison for dealing in LSD. Garrett Madison of Madison Mountaineering, a 45-year-old American with 14 Everest summits is “popular with the ladies, which is astonishing because he doesn’t say very much”, Cool says.

“He looks like an American superhero,” says Mary Broster, a 40-year-old British lawyer who climbed Everest in 2019.

One Austrian guide, Lukas Furtenbach, founder of Furtenbach Adventures, insists his money-rich, time-poor clients take delivery of a low-oxygen “hypoxia tent” to place over their beds six to eight weeks before going to the Himalayas to help them acclimatise. Cool is not a believer. “You wake up in the morning feeling slightly hungover,” he says. “And it’s going to ruin your sex life. What is your wife going to do? Sleep outside? And there’s no medical evidence for it working.”

However, in the still largely masculine world of mountaineering, shocking allegations have recently swirled. One guide has been accused of making unwelcome sexual advances towards his A-list clients at a hotel in Kathmandu and in a tent on an expedition to K2. Cool is reluctant to comment. “The whole thing is very unsavoury and doesn’t do the industry any favours at all,” he says.

Broster, who paid about $78,000 to climb Everest with Jagged Globe, said it was a “strange world” largely dominated by men of a similar age to Cool. She saw Cool at work on Everest on her 2019 climb and found him to be a “Mr Shouty”. “He was literally dragging his client through the Western Cwm [glacier in Nepal]. Some people love it and probably respond well to being shouted at to get a move on and to stop being pathetic. I suppose it’s tough love, and he’s very charming, but I wouldn’t like it.”

Asked about this, Cool says: “I’ve definitely developed as a guide. I used to be more shouty than I am now.” He adds that there are times when, for safety reasons, things “needs to be communicated very well and very clearly in the moment”, but acknowledges that not all his clients have liked the shouting. “[British explorer] Ranulph Fiennes used to respond extremely well to being shouted at, I think it’s partly down to his military background. Other clients, if you shout at them, will dissolve into tears and melt away. So you have to be super careful how you encourage or communicate.”

He does admit to the occasional bit of queue-jumping, unclipping him and his client from the communal guide rope to get ahead. “In order to avoid getting dead you’ve got to do something about it, which means getting off the rope and climbing past people going more slowly,” he says.

None of Cool’s clients have died on the mountain, though not all have made it to the top, particularly in the early years when he guided larger groups. He claims a success rate of 85 per cent compared with an industry average of about 65 per cent. The closest he has come to serious trouble on Everest was in 2018 when he guided the TV presenter Ben Fogle and Victoria Pendleton, the Olympic cyclist. Pendleton suffered a severe attack of altitude sickness at Camp 2 and had to withdraw. Cool and Fogle pressed on without her but ran into difficulty when their oxygen equipment failed twice. “I ended up doing the final bit without oxygen,” Cool says. “But we got to the summit and down safely.”

Back at Cool’s low-altitude home in the UK’s Gloucestershire, his family is used to him disappearing each European spring. The last year he did not climb Everest was 2015, when he was working instead in Bolivia – it may have been a narrow escape: an earthquake struck Nepal that year, killing 9000 people, including 22 in an avalanche on Everest. “It’s what he does, to us it’s just normal,” says his wife Jazz, whom he met in a bar in Chamonix. “But when he leaves base camp I stomach quite a lot of anxiety for the children. There’s no return in them being anxious.”

“If the shoe was on the other foot I’d be petrified,” Cool says, “but it’s a lot safer me being away with work than it was when I used to do a lot more trips for myself, when you’re not looking after a client and willing to push the boundaries more.”

He has spent more time on Everest than any other mountain but that does not make it his favourite. It is “work”, he says bluntly, referring to his job as a guide. He is dismissive of the Patagonia founder Chouinard’s suggestion that Everest is not real mountaineering: “I think it’s a bit unfair to say it’s not an achievement anymore. Rich or poor, they’re going to say for them it’s an achievement. If it’s a first for you, it’s an adventure and an achievement.”

He is reluctant to name any mountain he likes better. “It’s like with children, you can’t pick out a favourite. I just love expeditions, the simplicity of them.”

When not on Everest he is just as happy to “go for a hike in the Brecon Beacons or the Malvern Hills, which are even smaller, or the Black Mountains. I also go rock climbing for fun”.

The Cools have visited Nepal as a family but Jazz has “zero interest” in climbing Everest. “She gets cold stepping out of the front door,” her husband says. “She wears my Everest mitts while skiing – and that’s at Easter.”

If Everest becomes too much of a challenge he will not be left idle. “I could branch out doing unclimbed peaks. There would be clientele for that. I could get more active on the speaking circuit.” For the moment, though, he has no plans to hang up his helmet: he has signed up Everest clients for the next two years. Despite “all the bad stuff that goes on”, he finds he cannot resist the allure of the world’s highest peak.

“Everest has been super kind to me,” he says. “I like hanging out at base camp. When I left in May I wondered what it would feel like if it were farewell for good. I thought to myself, ‘God, if it’s the last time, I’m going to really miss it’.”

This story is from the February issue of WISH.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout