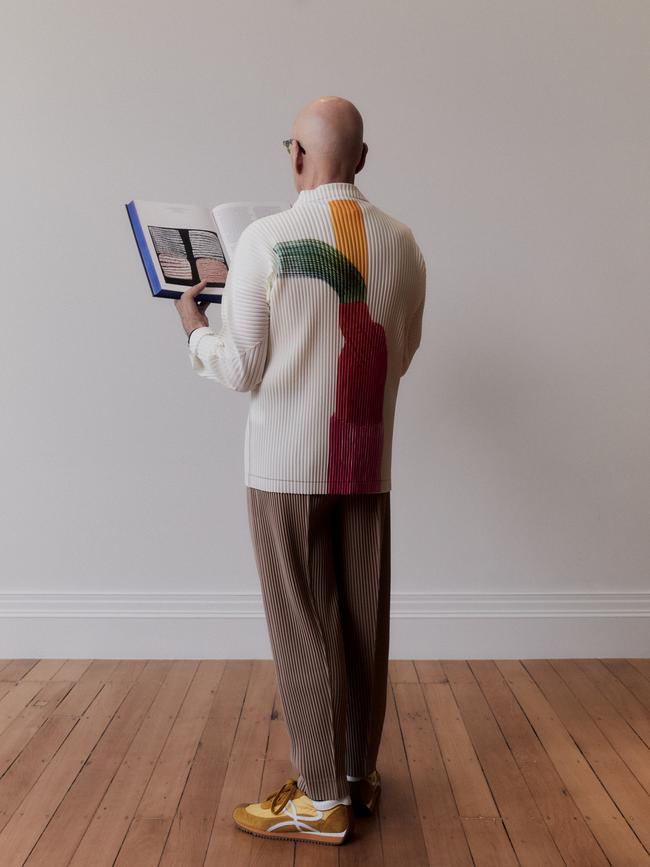

Barrister Peter Jopling on law, art, and the new Potter Museum

Throughout his 45-year career, the barrister counterbalanced his day job as one of Australia’s leading King’s Counsels with his passion for the creative industries.

One of Peter Jopling’s earliest memories is standing in awe and wonder before William Dobell’s celebrated painting of the US cosmetics entrepreneur Helena Rubenstein.

It was an experience so visceral that it led the eminent barrister to develop a profound and enduring passion for the arts, which continues to inspire him more than 60 years on.

“She was a rather overweight, smallish woman, but the jewellery around her neck and on her hands just brings her to life. I remember looking at this portrait and thinking, ‘Oh my god’, and expressing how ugly I thought it was as an eight-year-old boy, and my mother then explaining, ‘Well, what is ugly and what is beauty?’,” he says.

“My mother had a wonderful knack of taking us to a gallery, but only to see one work. Later in life, I asked her why. She said, ‘If I took you to walk floor after floor, you’d have gotten bored witless and been angry with what I was doing. So, I decided to take you to look at one work and explain why I was taking you to look at that.”

This lesson instilled in Jopling the desire to not only immerse himself in the art world but to also facilitate other people’s engagement with it.

Throughout his 45-year career, Jopling, 69, counterbalanced his day job as one of Australia’s leading King’s Counsels, representing some of the country’s most influential corporations and businessmen, by spending weekends visiting galleries and forming friendships with dealers and artists.

He deftly juggled a punishing professional schedule as a formidable interrogator while also serving as chair of five boards and a director on three others until his retirement from the law three years ago.

He currently chairs the Potter Museum of Art, the Menzies Foundation, the Melbourne Humanities Foundation, and the Australian contemporary dance company Lucy Guerin Inc. He is also a director of the Victorian Arts Centre Trust foundation and Lux Australis, a not-for-profit organisation dedicated to furthering Australian performing arts and artists.

Jopling’s connection to “The Potter” began a decade ago and has seen him play an integral role in the substantial renovation of the gallery located among the hallowed halls of his alma mater, Melbourne University, from where he graduated in law in 1976.

The museum, which reopens in May, has undergone extensive redevelopment by Wood Marsh Architects. It features an impressive new entrance and new and improved spaces for the museum’s leading collection-based learning programs. “Wood Marsh has cleverly repositioned the front door onto Masson Drive, which is the entrance to the university, lined with those elm trees, and we have that magical, star-buster front door. I call it the Anish Kapoor [British-Indian sculptor specialising in installation and conceptual art] moment because it’s so sculptural and beautiful and heralds the start of this new era,” Jopling says.

The museum will reopen with a landmark exhibition, 65,000 Years: A Short History of Australian Art, featuring more than 400 Indigenous artworks.

Jopling says the exhibition, curated by Professor Marcia Langton, Associate Provost at the University of Melbourne, Judith Ryan and Shanysa McConville in consultation with Indigenous custodians, examines the rise to prominence of First Nations art in Australia and the importance of Indigenous cultural and design traditions, knowledge and agency. Seven major new artistic commissions by leading contemporary First Nations artists will also be unveiled as part of the exhibition.

“Judith and Marcia will tell you that Australians really only began to understand the impact and the revolutionary and magnificent nature of Indigenous art in the middle 1980s, which is frightening to our generation who can’t imagine a world without an appreciation of Indigenous art,” Jopling says.

“The important thing was to place this art in the panoply of world art, not just to say, ‘Oh, over here is Indigenous art’, but to understand the significance of this body of work that’s existed for 65,000 years, and how it, like all other bodies of work, matures and changes with age and time and with different artists expressing themselves.”

Jopling’s philanthropic gaze is now firmly placed on how to give back to society through his involvement with various arts and educational organisations and institutions.

“I feel incredibly driven through all the philanthropic causes I’m involved with. I’ve met men and women I would otherwise never have encountered, and I feel that’s enriched my life so dramatically,” he says.

“You’re privileged if you’re afforded these opportunities, but it’s really important to give back. It’s what makes society that much more important, stronger, relevant and caring.”

He is particularly passionate about his role with the Melbourne Art Foundation, the world’s only not-for-profit art foundation. It holds the Melbourne Art Fair every February, showcasing established and emerging artists.

“You know what’s so special about that? We’ve had four [Indigenous] communities come, and several artists in the past few years have gone on to establish relationships with major gallerists. We’ve given back several million dollars in commissions, and then we give those commissions to gallery spaces around the country. This year, we’ll be doing two commissions, which is phenomenal. What other art fair does it?” Jopling says.

A driving motivation is making art accessible, and not just to an elite few.

“That’s one of the really important things, to bring into these spaces people who might never have imagined art was something that would interest them. Look, there are all these taboos about high-end culture. Art matters, and it matters to each and every one of us. I think it makes us more engaged, socially aware, inclined to be inclusive, and have a greater sense of beauty. A greater appreciation of culture is vital to a civilised society.”

Jopling’s private contemporary art collection is extensive and impressive. He is lending one of his pieces by Lena Nyadbi, Lirlmim and jimbirlal (Barramundi scales and spearheads, 2012), to The Potter for the opening exhibition.

“I’m deeply passionate about what I own, and it’s been a lifetime of collecting from the age of 18, and a very large amount of it I’ve still got. Somebody with a very fine eye looking at it all would say, ‘Well, that’s all pretty ordinary’. But it means something to me, and it’s my absolute love, not my greatest love, but it’s my absolute.”

Jopling shares his life with his long-term partner Richard Parker, founder of luxury skincare brand Rationale. They split their time between their home in Kyneton, where Rationale’s head office is located, and their apartments in Melbourne and Paris. More recently, they have travelled to the United States as Rationale expands into the North American market.

While he never had children of his own, he is a devoted uncle to his sister’s three sons and a grateful step-parent to Richard’s 24-year-old son Ezra.

“He’s an amazing young man, so I feel very privileged to be involved in his life.”

Jopling is invigorated and relishing using the skills he honed as a respected barrister to make a meaningful impact in his board and advisory roles. “The great thing about being a barrister is you get to cut through the crap and dissect what’s really important,” he says.

Physical fitness and a healthy diet are part of Jopling’s mission to stay active and engaged in later life. “I do focus on trying to stay healthy, but I love it. A couple of my close friends say, ‘Listen, you know, just watch it’. And I go, ‘Well, if I cark it having fun, that’s better than just sitting staring at a wall’. I don’t know how old you’re meant to feel at 70, but I don’t feel any particular age. I feel energised.”

This story is from the February issue of WISH.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout