Gloss leaders

THE Bertone Nuccio is nothing if not spectacular, but has the Italian styling house culture had its day?

WITH all the fuss about the local car industry recently it's easy to get confused by the figures. Take jobs, for example.

We know the number of people directly employed by our three local car-makers actually designing, engineering and assembling cars is about 15,000. But, of course, that vastly understates the hordes who rely on Ford, Holden and Toyota, one way or another, because of something called the multiplier effect.

It works like this. For every person hammering together a new car, there's someone who talks you into paying extra for rust prevention at the showroom. Then there's someone else who drives the tow truck when it breaks down. And yet another person who tells you that it can't be fixed under warranty. Once you start down this multiplier motorway, it never ends. It goes all the way from Gen-Ys in Super Cheap Autos to suits in Canberra who count everybody. Including each other.

What I've realised, though, is that the multiplier effect is a bit like the doppler effect, in that the tone of the answer depends on the speed of the subject. In this case, it depends on the rate at which the industry is accelerating towards a financial precipice. The faster it goes, the bigger the number. Which is why the entire population of Victoria is now dependent on Ford continuing to make the Falcon.

There's a similar thing going on in Europe, where car sales have been sliding since 2007 and are still reeling from the global financial crisis. In the US when sales crashed, its three troubled auto giants closed dozens of plants and killed off entire brands including Hummer, Saturn, Pontiac and Mercury. It's now growing again and rehiring. The government even got some of its money back. In Europe, it was a different story. There it was a case of NIMCY - a similar phenomenon to NIMBY, but meaning Not in My Car Yard. The commitment to the European common weal stopped at the factory gates. The result was one brand casualty, Saab, which wasn't selling any cars anyway, and the closure of one panel-beater in Estonia. Everyone looked after their own.

According to the body that counts these things, the European industry now employs almost 13 million. If it was all located in Greece, every man, woman and child would have a job. But what it means in practice is that the only place the industry all comes together every year to roll out fresh metal is the neutral territory of Switzerland. It doesn't need a car industry because its economy is based on something much more secure: banking.

The Geneva motor show is also remarkable for being the only A-list event where second-tier players jostle for wing-mirror room on the same floor as the majors. Where names such as Mansory and Gemballa, Brabus and Sbarro show off pimped versions of mainstream cars and their own extreme ideas. In Europe, there really are people willing to gold-plate a Merc then cover it in Swarovski crystal. Or think a Ferrari a bit underpowered and in need of a 787-sized wing.

You could come away believing that a good proportion of those 13 million are busy catering to the shag-pile sensibilities of the only ones left in Europe who can afford cars, namely bankers. Until you stumble across the remnants of the carrozzeria - the Italian styling houses which have influenced design thinking across the industry for decades. Companies with mellifluous names like Pininfarina, Giugiaro and Bertone. These are the real geniuses behind many of the industry's milestones and most of its memorable supercars. Their numbers have been whittled down over the decades and any that haven't been gobbled up - Italdesign Giugiaro became part of Volkswagen two years ago - have steered a perilous path through the recent upheavals.

This is especially true of one of the most famous, Bertone, which celebrated its centenary at Geneva with a striking wedge-shaped concept called the Nuccio. Named for one of the company founders, the Nuccio will be the centrepiece of an anniversary roadshow that takes in everywhere from China to the US. More than that, it celebrates the successful struggle to keep the company alive by Nuccio's widow, Lilli, after her husband died on the eve of the Geneva show 15 years ago. A decade later, Stile Bertone was bankrupt but Lilli bought back the farm, including most of its museum collection, while pulling the company back from the brink.

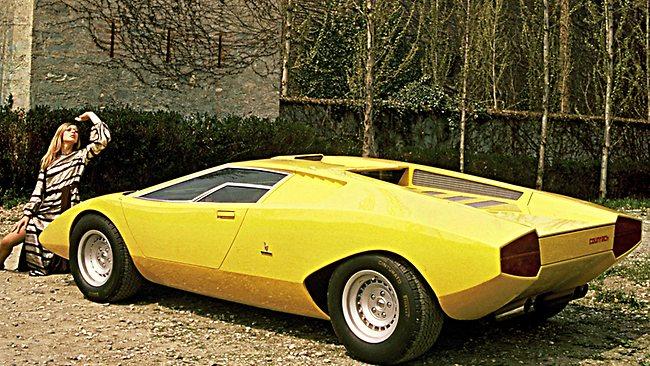

The Nuccio show car references three of Bertone's most influential designs, including the Lancia Stratos Zero and Lamborghini Countach, familiar from car posters to millions of baby-boomer boys. A two-seater wedge with a 4.3L V8 behind the cabin, it's impossible to see out the back of the Nuccio so a camera feeds an LED screen that's a virtual rear window. It's a vehicle to display the company's expertise and shows there's plenty of talent worth saving among those employment numbers.

But it's also a metaphor for Bertone itself, and even the whole Italian styling house culture. Because it's hard to believe that its best days are not in the past.

In the rear-view mirror of its history, objects seem larger than they are.

Philip King is the motoring editor of The Australian.