When is a unicycle actually an Everest to climb? When you’re 14

Concussion, a busted wrist, broken foot, black eyes: nothing could deter Tim Douglas from pursing his first, one-wheeled love.

The first unicycle rolled into my life on Christmas Day, 1994. A gift from my grandparents, it had been wrapped, like some ancient curio, in a white sheet. Shepherding the angular apparition through the living room on his way to the Christmas tree, my grandfather swore loudly as the gift reared about violently, searching for a point of balance, under his hand. “Bloody thing has a mind of its own.”

When the sheet was, theatrically, removed by my pensioned progenitors, I was awestruck. A resplendent vision of chrome and rubber, the unicycle was the most beautiful thing I’d seen. My 14-year-old self marvelled at its form. A cylindrical column at one end forked around a freshly stubbled tyre, its spoked wheel affixed with a brace of spiked metal pedals. At its other extremity was a padded saddle, unimpeachably plump and sporting a small chrome mounting handle. A sticker on the cycle’s backside proclaimed “Wilson’s Bikes”. But this was no bike. This was something altogether different. This was a mountain to climb. I had no idea how to conquer it. All I knew was I was in love. Head over heels.

FIRST LOVES

Good Angela, Bad Angela: no mystery who stole my heart

Whether she was a witch, a detective, a murderer or the mother from hell, Angela Lansbury captivated in all her roles.

Besotted and bespotted – a life enlivened by leopard print

Jenna Clarke plunged into the world and ethos of her adored, feisty (and possibly feline) grandmother.

How I fell head over heels – and heels over head – in love

Concussion, a busted wrist, broken foot, black eyes: nothing could deter Tim Douglas from pursing his first, one-wheeled love.

Country life made the new world home

During two years in Wee Waa, Rosemary Neill at last started to feel she was having a truly Australian childhood.

My heart was racing with love for a Bambina

She’s never loved a car as much since: Helen Trinca’s Fiat 500 was sheer chic and gave her the freedom she craved.

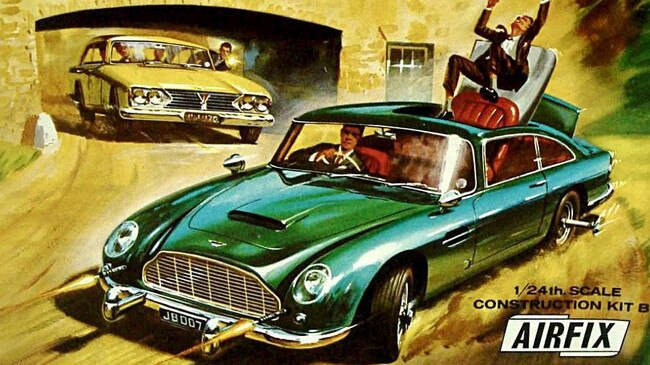

Life in plastic perfect for a model child

A childhood on the move meant frequent changes of locale and school, but the fascination with Airfix models was unchanging.

Dear John, sorry may not wash … but I do feel bad

A real-life encounter with a teenage fantasy crush was doomed to crash and burn.

Mamma mia! Thank you for the music, Molly

ABBA’s arrival in mid-70s Australia was greeted with great excitement by the youngest of the Meagher boys.

Blissful age when the girl next door was truly mine

Tom Dusevic and his first love bonded over toys, books, tea parties and Romper Room and shared a roof, but not a bed.

If music be the food of teen romance …

Geordie Gray was shy, but who needs Cupid when you have MSN Messenger on your side in pursuing love?

How I discovered just what lies under Minnesota

Laid up in bed, Cameron Stewart’s bored gaze fell upon the America wall map, and stuck. Decades later he is still looking.

Rustling up true love

After cooking her way through childhood, school and university Bridget Cormack has found a love who shares her passion.

X-Men, Dr Strange, Wanda et al made me marvel at their marvellousness

In a world where TV was still monochrome, the vibrant colours of Marvel comics were almost as arresting as the heroes portrayed.

Pony tale full of feeling, captured at a gallop

An illicit equine affair kindled a passion for horses, but precipitated a painful family drama when all was at last revealed.

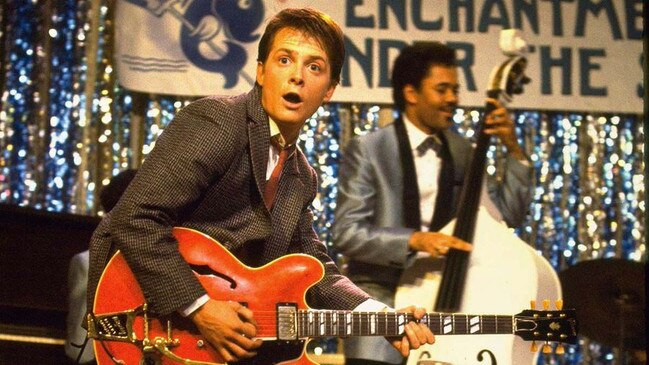

My first love was time-travelling Marty McFly

Trent Dalton leads our new series, in which our writers recall the poignant and funny moments of their early passions.

An old friend of note who waits faithfully for me

How Andrew McMillen re-discovered his first love after years of playing the field.

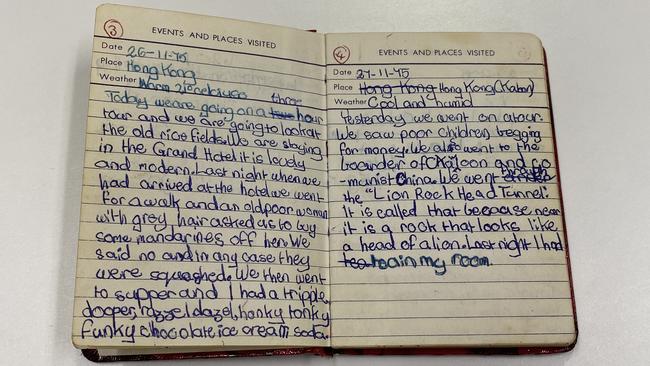

First-time flyer on long-distance date with destiny

Two kids left with their families on their first overseas flights, in the 1970s. Both wrote diaries, recording their excitement. What happened next?

Crystal set radio was my ticket to ride

For a Melbourne-based boy who couldn’t wait to embrace the new 60s music, a crystal set radio was the ticket to ride.

“Perhaps it was heels over head?” I did my best to explain the accident to the doctor, insofar as I could recall it at all. There had been a technical issue with my maiden voyage. The GP had her own word for it: “Concussion.” That fall – the unicycle having rolled unceremoniously out from beneath me, propelling me into a wall – would be the first of countless mishaps over the course of the next three decades. The broken foot, the busted wrist, the black eyes, the gaping gash in the scalp. All that was ahead of me.

For now, I was besotted. I barely emerged from my room that summer (perhaps not unusual for a teenage boy; but let’s call mine a “uninistic” pursuit). By the time autumn rolled around, I could ride with a rudimentary level of proficiency. I rolled to breakfast. I spun down to the shops. I took it to school, giving lessons in the playground. I learned some acrobatic skills and started juggling – first balls, then juggling clubs, and then mum’s kitchen knives, much to her horror. Eventually I bought some fireclubs and professional juggling knives, and found work.

Festivals, parties, shopping centre openings, town fairs. At one point the young impresario Michael Cassel – the country’s leading international arts producer – hired me. (Okay, so he was 14 at the time but still I thought I was going places). I busked and got some work with a circus before landing a job, while at university, with councils running circus skills workshops.

That unicycle was always by my side. Within a few years, I had bought a new one. A tiny thing. Maybe a foot high. My 40-year-old hips now wince at the flexibility I must have needed to ride it, but I mastered it, impressing no one but myself.

I moved to the Czech Republic, and found Prague tragically to be devoid of unicycling shops. A year later, I moved to Edinburgh, Europe’s cultural capital, but I couldn’t find a unicycle to save myself. It wasn’t until I visited London’s Camden that I tasted the sweet succour of the circus shop. I put a deposit on a nice red unicycle before realising carting a backpack and a wheeled stick around the world might have its drawbacks. I got my deposit back, and put my bank (and corporeal) balance on hold.

When I returned to Sydney a few years later, my journalism career in motion, I disappeared into the unicycling wilderness. I got married, and my little family of wheels was superseded by far more needy human ones. It wasn’t until my elder son’s fifth birthday that I decided it was time to roll out Old Faithful. The tyre was flat. Rust had set in. It needed some oil, and so did I, and so with liberal doses of WD40 and Deep Heat respectively, we were back together. I began riding again in the wee hours, rediscovering its meditative salve, and embracing the nightly communion of breathing and balance.

My family – wheeled and legged – began expanding. With each child seemed to come a new unicycle. A caramel number accompanied the birth of my second son; and then, with the arrival of my daughter, came the piece de resistance: The Giraffe. The 2m-high, chain-driven monster is a tricky beast to master – it requires its rider to scramble up its shaft and mount the saddle and pedals simultaneously. After months of practice, I was up and riding. Until I wasn’t. The last time I was cycling at altitude — cleaning the house’s gutters (my wife’s suggestion) — I broke my foot on the dismount. It wouldn’t have happened on Old Faithful.

People generally ask two things of unicyclists: How do you do it? And, more pointedly, why?

The how is easy: practice. The why is a more complex proposition. A psychoanalyst might have a field day with it (“Which bicycle hurt you?”), but I remain steadfast in my response. When I was 14, the unicycle was my Everest. Why did I ride it? Because it was there.

Tim Douglas is editor of Review.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout