The top heart surgeon who eats salt

“We’ve seen so many theories of heart-disease baddies debunked,” says a prominent doctor.

One night, after the usual hectic Monday in the operating theatre, one of the stars of Royal Papworth heart hospital in England was on a gym treadmill when his chest began to ache. As a surgeon, Samer Nashef knew what this was: it was angina, harbinger of heart attacks and heart surgery.

Sub-vocalising variants of the F-word, he went with his workout companion, a fellow surgeon, to a pub to down a pint of pale ale and order a burger with all the trimmings.

“So that was 2012,” says Nashef in his shabby office overlooking the Papworth duck pond. “Gosh, seven years ago. And I’m still alive.”

In his enthralling and outspoken memoir, The Angina Monologues, he records what happened next. First, naturally, he ignored the symptoms, but they returned at his next gym session. So he spoke to a Papworth cardiologist, who diagnosed crescendo angina and recommended a scan. It revealed calcium in his arteries.

In the most important one, the left anterior descending — nicknamed “the widow-maker” — there was so much it was obstructing the blood flow.

Nashef asks if I want to see his plaque, an invitation that from another medical titan might mean having to admire a brass plate on the door of a ward named after him. Here, however, I stare at a moving X-ray on one of Nashef’s quartet of computer screens.

In the crucial artery, the walls have thickened and the narrowed passageway is cloudy — the remains of a piece of ruptured plaque. Nashef had seen it on the screen in real time and was hugely relieved because the narrowing was no more than 20 per cent. It meant a stent to open the blood vessel was unnecessary. So was a coronary artery bypass grafting (a CABG, or “cabbage”). On the downside, he still had coronary heart disease.

I know what you are thinking. Of course he has heart disease: he drinks beer and eats burgers. “I don’t actually think that drinking pints and eating cheeseburgers makes any difference to heart disease. I think it’s how many cheeseburgers,” says Nashef, who is a handsome 64-year-old of Palestinian descent and not overweight.

“There isn’t really that much evidence that links what you eat with heart disease. An awful lot of so-called research looks at one particular lifestyle and then compares it with another lifestyle and comes to all sorts of conclusions about lifestyle, but one of the more elementary things in science is that an association does not mean causation. We have seen so many theories of heart-disease baddies debunked.”

Give me an example. “Well, red meat, butter. Look at coffee. There must have been dozens, if not hundreds, of studies, but all they do is take a lot of people who drink a lot of coffee and a lot of people who don’t drink a lot of coffee and then find out what levels of heart disease are in them. And that, to me, doesn’t answer the question about causation.”

So people drinking a lot of coffee may also be buying a cream bun and getting obese? “Or maybe they enjoy a cigarette with their espresso.”

It is not conclusively proven that high cholesterol in the blood universally leads to coronary artery disease. Plaque is partly made up of cholesterol, but not necessarily the cholesterol contained in the blood. Even if it were, it is not certain that diet affects blood cholesterol (most cholesterol is generated by the liver). To be safe, however, if you have high blood cholesterol, take statins. “You can definitely reduce it a little bit by quite draconian diet changes, but you can reduce it a hell of a lot more by taking a tablet.”

Aren’t we already over-medicated? “We also drive too many cars and take too many planes. We’re an extremely artificial species now, so what difference does it make if it’s proven to be good? Of course, I am on a statin.”

If he is the angry man standing up for one wrongly accused suspect, however, that suspect is salt. “I add salt to everything. By the shedload … Everybody tells you to cut down salt. If you’re sitting at a table and you go heavy with a salt cellar, people tell you, ‘You and your salt.’ And the fact is, the effect of salt on survival has never been proven.”

He refers me to analysis by British non-profit organisation Cochrane of seven randomised controlled trials on salt. When people were told to eat less, their blood pressure came down a tiny bit, it concluded. However for people actually with heart failure, reducing salt lessened their chances of survival.

He is sceptical whether that old villain stress stops hearts. “It is possible. If stress increases your normal adrenalin level, then that causes constriction of blood vessels. You can imagine the mechanism, but people have studied the type A personality and the type B personality and its impact on heart disease, and I don’t think they’ve managed to prove anything.”

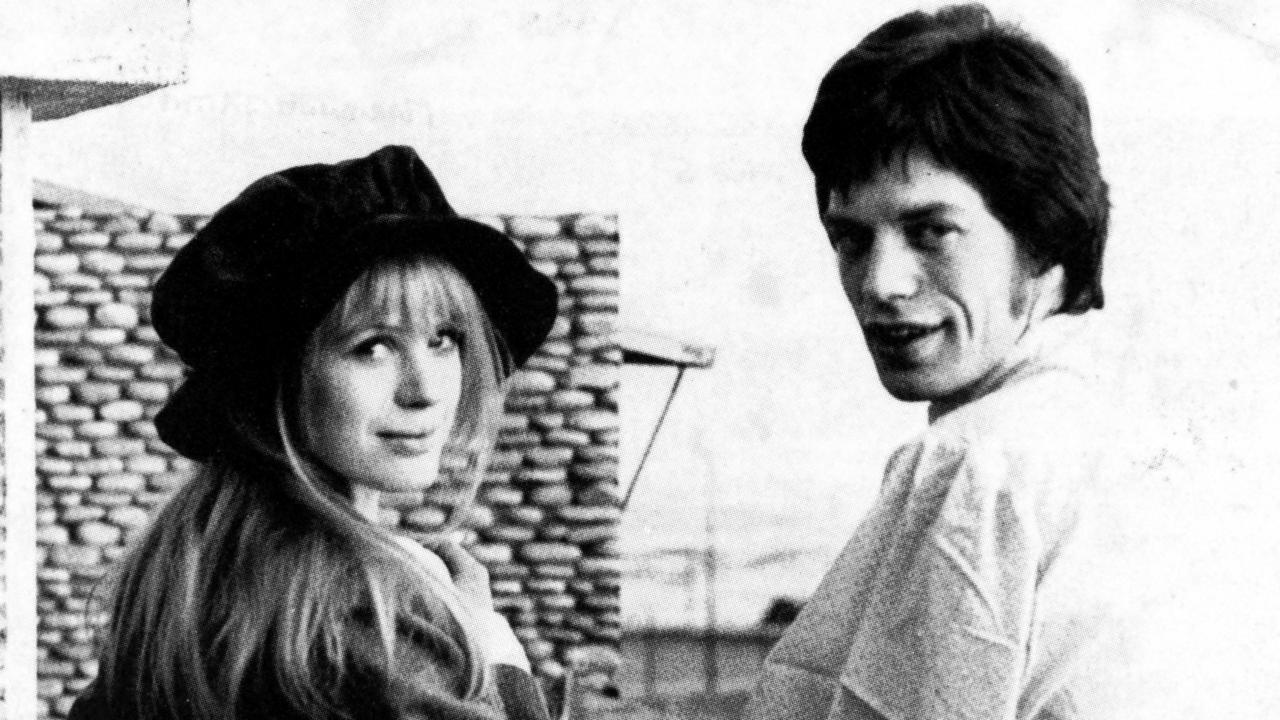

He does concede that stress may not help marriages, including his, which ended in separation 10 years ago. He is now with Fran Malloy, a nurse turned photographer, whom he met in the early 1980s before he married. She moved to Australia, got married, then contacted him out of the blue. “And we got back together after my marriage was finished.”

How much did his four children see of him while growing up? “It was never enough. I would often leave before they woke up. I’d come home after they had gone to bed, often. Many of my weekends and nights were on call, so they didn’t get to see me that much then. I did try quite hard, certainly harder than many of my colleagues, to improve my availability for family life, but it probably wasn’t sufficient for them. Fortunately, I get on really well with them. They have forgiven me.”

What, then, I ask, does cause heart disease? Genes, of course, about which we can do nothing, ditto getting old. There are two indisputable factors we can work on: we can quit smoking and we can shed weight. We also can exercise. For Nashef, what is most important is that the right exercise builds muscles, and muscles burn calories, whereas fat is dead weight.

“We have a choice,” he writes, addressing anyone over 30. “Let muscle loss continue but eat a lot less, or fight it with resistance training and eat more. I chose the second option because I really like food.”

He is clear he has heart disease because he smoked cigarettes in his youth and because of his genes. His father, a UN official and educationalist, died aged 62 and his mother, a writer, died in her early 70s, both of heart disease. Neither helped themselves by being smokers and living the sedentary life of the intellectual.

However, I say, imagine we take his advice and still end up with him at the end of our bed. “Then you are unlucky,” he says.

What else may reduce our chances of survival? He identifies a potential peril we may not have considered: keyhole surgery. Minimally invasive heart operations have become “sexy”, he claims. Mitral valve repair, for instance, usually involves splitting a breastbone north to south. Limiting a surgeon’s access, necessitating the use of telescopes and long instruments, it makes the procedure longer and riskier. If it makes it too long, a surgeon should “eat humble pie” and open the chest.

“Unfortunately, some surgeons do not see things that way. Carried along by a wave of ego, arrogance and grim determination, they persevere,” he writes. Patients in Britain have died as a result, he believes. If you are offered a minimally invasive heart operation, check your surgeon has done lots of them and make them promise to bail out if things get dicey.

I had hoped the days of the arrogant Sir Lancelot Spratt had passed. Are they creeping back? “There is a bit of that and it’s something I feel quite strongly about. You must never lose track of what you’re trying to achieve for the patient, rather than what you’re trying to achieve for yourself.”

I suppose it appeals to a patient’s vanity too: no zip down your chest. “But it’s more appealing to the surgeon who says, ‘This is something new and sexy and I can do it and my colleagues can’t.’ That may be true and it may be fine, but it should never put the patient at undue risk. When patients are put at undue risk it’s often due to ego.”

When my colleague Sathnam Sanghera interviewed him four years ago about his previous book and asked about a tool he had co-created to predict the outcome of heart surgery, Nashef said it was a lifesaving breakthrough worthy of the Nobel prize. Has he ever struggled with his ego?

“No. My ego is rather modest. I never imagined that I was born to do this job or had special skills or special powers. Not at all. I’m not cack-handed, but I’m not particularly gifted with my hands. I am, if anything, gifted with my head and at making good decisions.”

Last month, after 27 years, Nashef performed his final operation at the old Papworth. He will not have an office in the new building, or even his own desk — nowhere to hang his paintings, nowhere for his four computer screens. As he leads me out, however, I notice one of those rock-salt containers that is also a grinder on a shelf. Oh yes, he assures me, he will be bringing that.

The Times