The best contemporary Australian artists in 2025

Feeling behind on who’s who in contemporary Australian art? These are the names you need to know this year.

There’s a new generation of Australian creatives taking the contemporary art world by storm. Hannah-Rose Yee meets with the biggest local names to find out what inspires them and how exactly they navigate the practice of making art in 2025.

The Australian artists you need to know in 2025

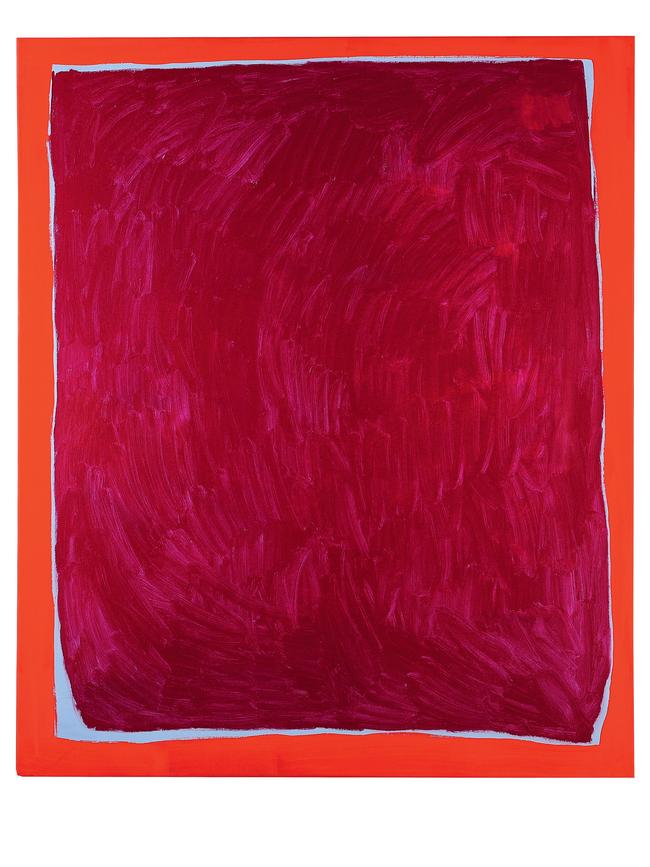

Marion Abraham

Life is a circle, meaning we often find ourselves right back where we began. So it was for the painter Marion Abraham, who recently moved home to the same hill in Tasmania upon which she grew up, where all you can see is mountains, sky, animals and trees. “And my sister, who lives across the paddock from me,” says Abraham. “To my complete surprise I love living back here. The backdrop, she says, provides ample inspiration for her brooding and visceral oil paintings. “Every contradiction I see around me fuels the contradictions I try to navigate in my work. A mixture of destruction, hope, beauty, renewal and resistance.”

Originally a potter, Abraham received her Fine Arts degree from RMIT and is now represented by Sullivan + Strumpf. Her history with clay informs the way she paints; Abraham will use her hands to mark her canvases, a process that “often feels more like sculpting than painting”. Working by hand also allows her to expertly balance light and shade, the colours bleeding into each other and copper foil highlights catching the eye.

In 2024, she was shortlisted for The Churchie Emerging Art Prize for a three-panel panorama called Joyride Series (2024). The work explored Abraham’s Lebanese heritage, which she will also engage with through a research project at the Arab World Institute in Paris, as part of the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s 2025 Cité Internationale des Art Paris residency. After that? Back to Tasmania. “There is a southerly wind that comes through on a cold evening and nothing is more beautiful to me.”

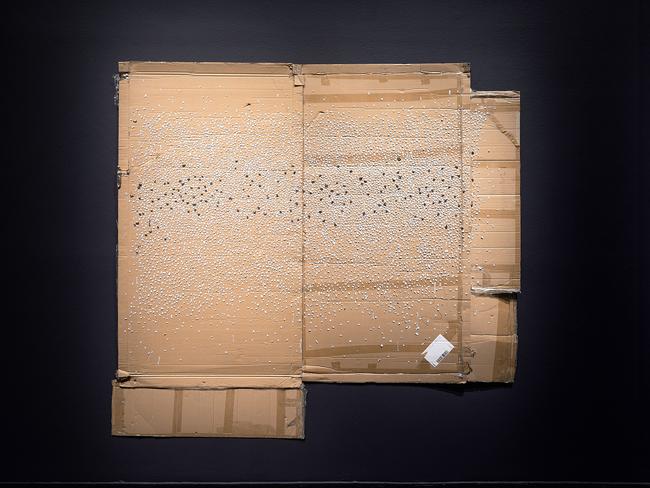

Teelah George

The passage of time is keenly felt in artist Teelah George’s works. Take Perpetual Horizon (2024), fashioned from a sprawling blue PVC curtain, discarded from a truck, embellished with bronze rings and first exhibited at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art as part of the Macfarlane Commission. It came about, George says,

after years spent snapping photos of the “dilapidated” plastic sheets as they zoomed past her on the street. “My camera roll is full of these,” she says. “For me, they became travelling drawings, a surface created through weathering and incidental friction, keeping both time and space.”

When an idea becomes an obsession is when George is most creative. Her mixed media work, which has been exhibited at the NGV as part of 2023’s Melbourne Now and is held by the Museum of Contemporary Art, often uses found materials – PVC sheets, cardboard, even Blu Tack – to interrogate how an object’s purpose is both stored and transformed. Some of these are then intricately embroidered, which George describes as “like a slow-motion painting process”. In her studio, locked into creative flow, George says this embroidery unfolds in the moment. “The work tells me what to do and I have to listen.”

At present, George is working on her solo exhibition for gallery Neon Parc in Melbourne this April. She moved to the city in March 2020, straight into lockdown. “In many ways it was a soft introduction,” she says, remembering long walks and slow cooking. “Melbourne is such a hub for the creative community,” she says, “and it is so important to be amongst that as an artist.”

Renée Estée

The Melbourne family home of artist Renée Estée was, she remembers, “very small but creatively alive. I grew up drawing everything around me, everything on the walls and all of the objects adorning the surfaces. It’s funny because this has crept into my practice so much – creating artworks that feel adorned or shrine-like.”

Estée relocated to New York to complete her MFA at Hunter College, where she is now based, and the tension between her adopted home and Australia feeds into her large, abstract paintings. “When I first landed in New York, I was so struck by how the landscape was essentially vertical. I was always looking at giant skyscrapers,” she says. “My paintings were already large-scale but became larger … I wanted to keep looking up.” If the scale screams America, Estée’s palette recalls our sunburnt country: ochre, sand and blush pink. Her canvases are often embellished with childhood mementos rescued from a box she carried with her to New York. “The works started becoming archival, as well as acting as a doorway back to Australia.”

In 2024, Estée completed a residency in Cornwall, where the rhythm of the sea guided her brushstrokes. She returned recently, painting at night under a silvery sky, and these new works will be exhibited at her gallery COMA later this year. One hope for 2025 is a return to Australia. “Now that I’ve been away for five years, I’m feeling in need of spending some time painting back home.”

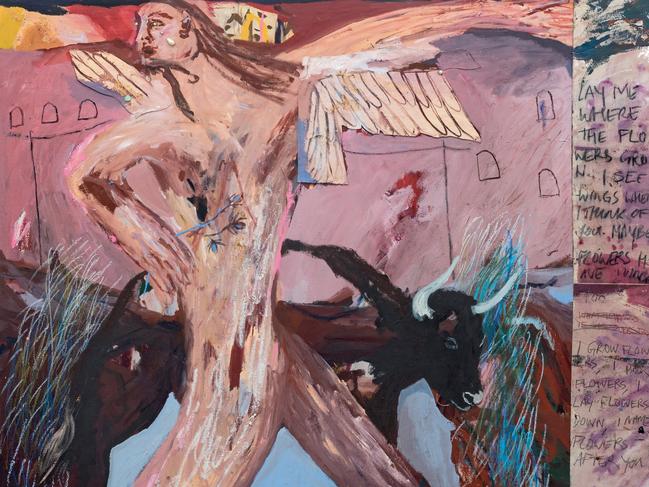

Tiarna Herczeg

When Tiarna Herczeg starts to paint, she feels as if she’s floating away on a cloud. “Like my consciousness leaves my body and, at the same time, I’m right there in the thick of everything, all at once,” she explains. All the artist needs is sunlight and an empty calendar; once, in her studio in the Sydney suburb of Marrickville, Herczeg sat at her easel for more than 10 hours straight. “That’s the way I work,” she says. “I usually start and leave a painting in one sitting.”

Growing up, the Kuku Yalanji and Hungarian woman never considered art to be a viable career. “I don’t think I ever had one single light bulb moment. The light bulb has always been on; I guess I’ve been slowly making my way towards the light.” But the emerging artist has made a name for her bold canvases splashed with pigment, exhibiting in 2023 at Sydney Contemporary and in a residency at Darwin’s Laundry Gallery.

It was Herczeg’s first trip to the Northern Territory – “an unforgettable place”. There, the First Nations artist’s usual colour palette of jet black and rust red melted into turquoise, canary yellow and the softest lilac. “I took the colours from the landscape and turned the saturation up, because I was feeling energised,” she reflects. This year she will make her first trip to Hungary, where she can trace her father’s lineage. While there, Herczeg will stage huge works across two floors of a Budapest gallery in a show twice the size of her previous largest exhibition. “The show is about migration, belonging and identity,” she shares, “summing up my experience as someone with dual identity … It’s special.”

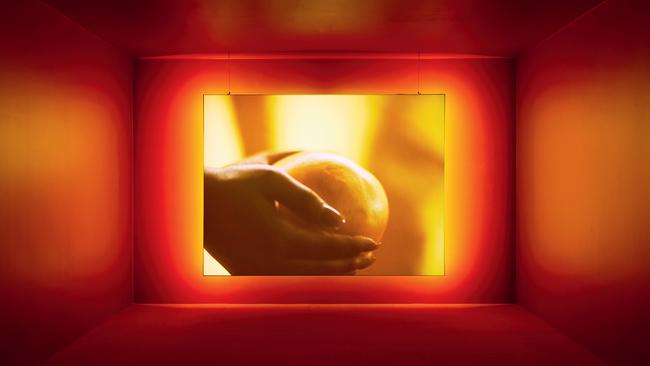

Monica Rani Rudhar

Monica Rani Rudhar works in many mediums, making art from video feeds, dried spices, Romanian embroidery, terracotta and gold. And her ideas can strike anywhere: in the shower, waiting in traffic, walking through Indian supermarkets or the sari shops that stud the Sydney suburb of Harris Park. “I feel creative when I’ve been looking through family photos, hearing family stories shared around the dinner table and looking through heirloom jewellery that has been kept safe in velvet boxes,” she reflects.

What makes an heirloom is something the artist, who has Indian and Romanian heritage, finds herself returning to over and over again. It is at the heart of her work Earrings That My Mother Kept For Me (2024), a large-scale replica of a treasured keepsake, on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Primavera. “For me, Indian jewellery has been one of the few things that link me back to my family and culture.” Using a large-scale drawing as her guide, Rudhar assembled the pieces by hand from terracotta and brass wire before firing the work three times. All up, a pair of replica earrings can take two months to complete. “I’m pretty focused during the hand-building process,” she says. “A lot can go wrong if I am rushing.”

Next is a solo show at Martin Browne Contemporary in June, as well a project with the Casula Powerhouse. Only a few years ago, during the covid lockdowns, Rudhar identified something she could process through art: the grief of disconnection from her extended family, and “grappling with not feeling fully Indian, Romanian or Australian. It was at this time that I felt like I had something to say.”

Rainbow Chan

When she was six years old, Rainbow Chan moved with her family from Hong Kong to Sydney. Then then the long-distance calls began. Using phone cards from the Asian grocer, Chan’s mum would speak for hours to her sisters back home in Hong Kong. “In Cantonese, we call this ‘cooking telephone congee’, because of how long it takes,” Chan says.

Through these winding conversations, she would hear snippets of Weitou, the dialect spoken by the earliest settlers of Hong Kong and her mother’s native tongue, which is in danger of dying out. Since 2017, the artist has been learning the language and these studies have informed every aspect of her multidisciplinary practice, which spans live performance, music, painting and calligraphy, each medium used “as storytelling tools to navigate the complexity of human experience”.

Visitors to the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Primavera can hear Weitou in Chan’s Long Distance Call 長途電話 (2024) – in memory of her late aunt – comprising rippling silk paintings of flowers in bloom, a soundscape and a projection of animated neon butterflies. Earlier this month, Chan staged her acclaimed Weitou solo performance The Bridal Lament 哭嫁歌, as part of Sydney Festival, and these songs will soon find a home on her forthcoming album. “When I heard the Weitou laments for the first time, something inside me awakened,” says Chan. “When I sing them, my voice feels boundless. I am one with all the women who sung them before me.”

These days, when Chan spends time with her mother, a new thread of connection whispers between them. “I can see something light up in her eyes when she speaks in her mother tongue.”

This story is from the January issue of Vogue Australia, on sale now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout