Yunupingu: the powerhouse truth teller who changed Australia forever

‘You’ll be back,’ Yunupingu told my family when we left Gove. He was right.

Yunupingu was already a force in Canberra in 1976 when I landed on the Gove Peninsula with my parents and little sister in northeast Arnhem Land. Not that I had any idea while growing up in Gove that prime ministers listened to this charismatic young man or that he had just changed Australia forever.

In the small town of Nhulunbuy, built by Swiss-owned miner Nabalco over the objections of his people, Yunupingu was a familiar face who stopped to chat to mine workers at the boat club. In 1981, he pulled over on the dirt road between town and Dhupuma College where my mother Narelle was quietly panicking in a stalled car. She was a long walk from a phone box. He got the Land Rover started, making jokes and conversation while he worked, and waved her away as she gushily thanked him.

He was interested – or very convincing at showing interest – in the Gumatj words that new arrivals had learned. Looking back, his grace was amazing.

Yunupingu was made Australian of the Year in 1978, two years after my family arrived on Yolngu country for the bauxite. He was honoured for ushering in the nation’s first land rights laws. Those laws were too late to stop the mine that brought thousands of non-Aboriginal people to the pristine headland of Gove to dig up, refine and export bauxite. Those laws were enacted because his people had been unable to stop the mine or have any say in it at all.

What Yunupingu helped achieve through the Aboriginal Land Rights Act of 1976 is considered by some to be more significant than Mabo, because Mabo flowed from it.

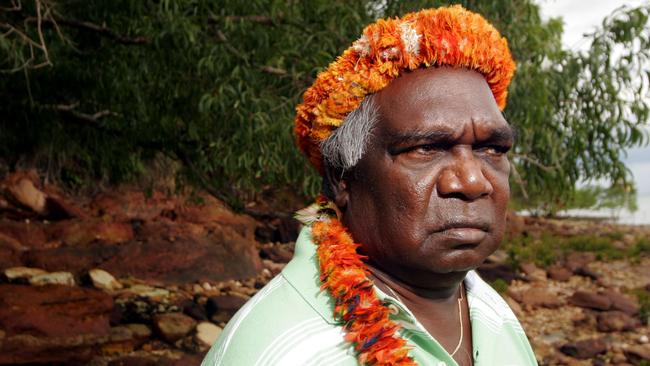

When Yunupingu died aged 74 this week, the Gumatj clan leader was honoured for a lifetime of advocacy for Indigenous Australians that enriched us all.

He lived his entire life on his beloved Yolngu country in the northeast pocket of the Northern Territory. This remote patch is famous now for the annual Garma Festival he created with his brother, Dr M. Yunupingu. It is inarguably the nation’s most important Indigenous cultural event and a place where policy is made.

But when Yunupingu was emerging as a powerhouse, most Australians had never heard of Arnhem Land or its only town, Nhulunbuy. My father, Greg, was among them. He first saw the word Nhulunbuy in a newspaper advertisement for tradesmen.

He was a boilermaker from the goldfields town of Kalgoorlie who had always dreamed of the sea. In Nhulunbuy, he built a boat – made of steel, because that is what he knew how to do – and for a couple of years my family lived along the coast where Makassar seafarers had been trading with Yolngu for sea cucumber since at least 1700.

One of my favourite places was the bright azure bay at the appropriately named Truant Island. My sister Chelsea and I were supposed to do school by correspondence with an office of teachers in Perth but we were always scheming to get out of it. We preferred to fish or swim in the bay, or play with our youngest sister, Bree. In the early 1980s crocodile numbers had not recovered from the days when killing them was legal. Still, I believe we were a bit mad to have stepped into the sea.

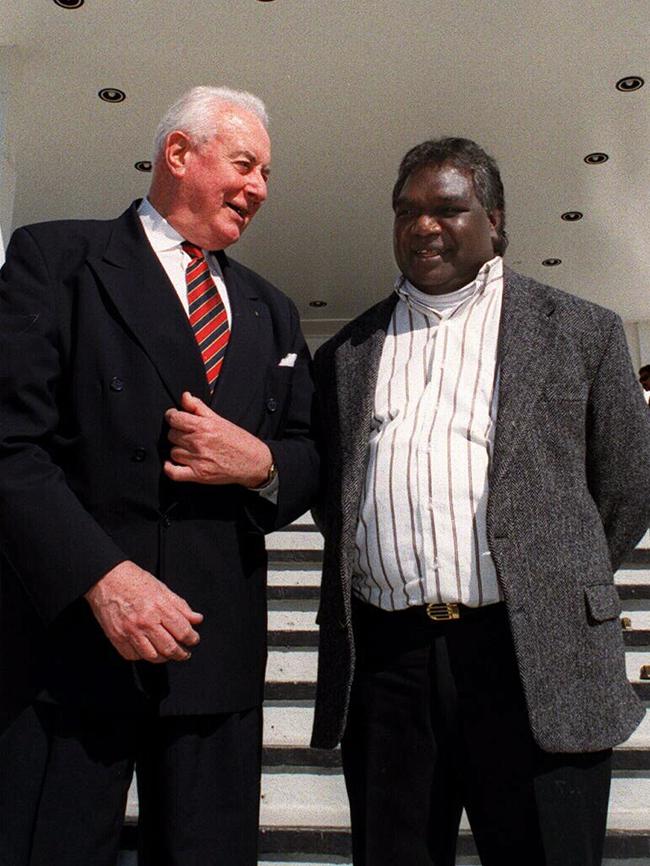

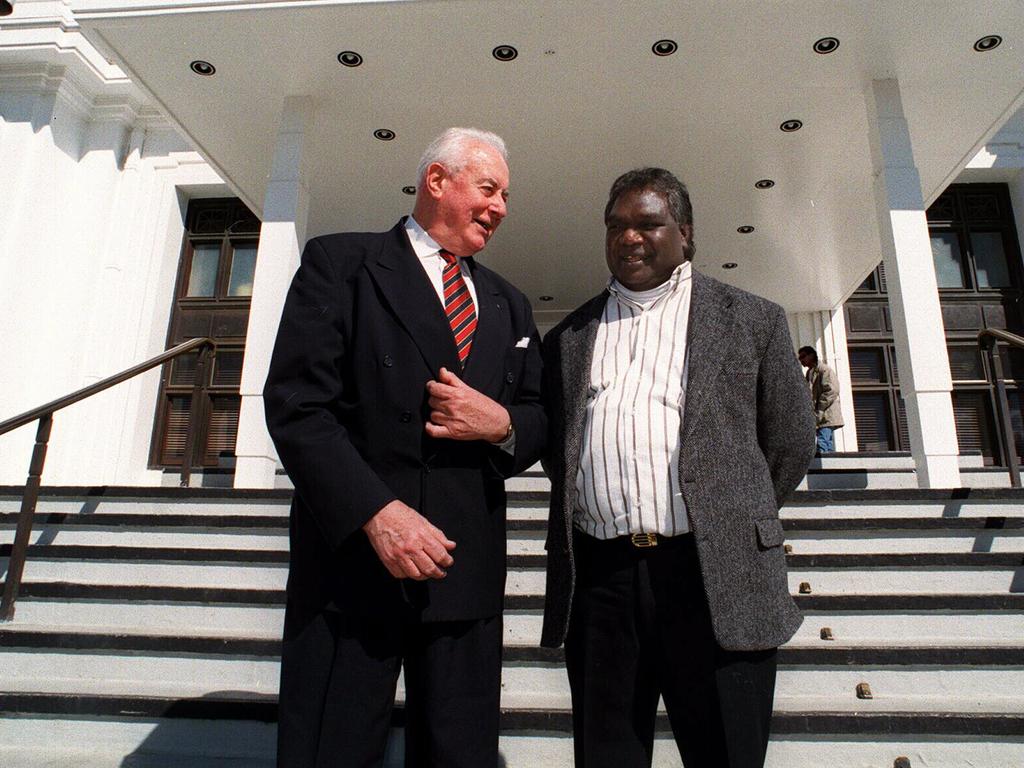

During this period, Fred Chaney was Aboriginal affairs minister in the Fraser government and listening to Yunupingu. The clan leader was now the inaugural chairman of the Northern Land Council, established to do the work that was not possible before land rights became law.

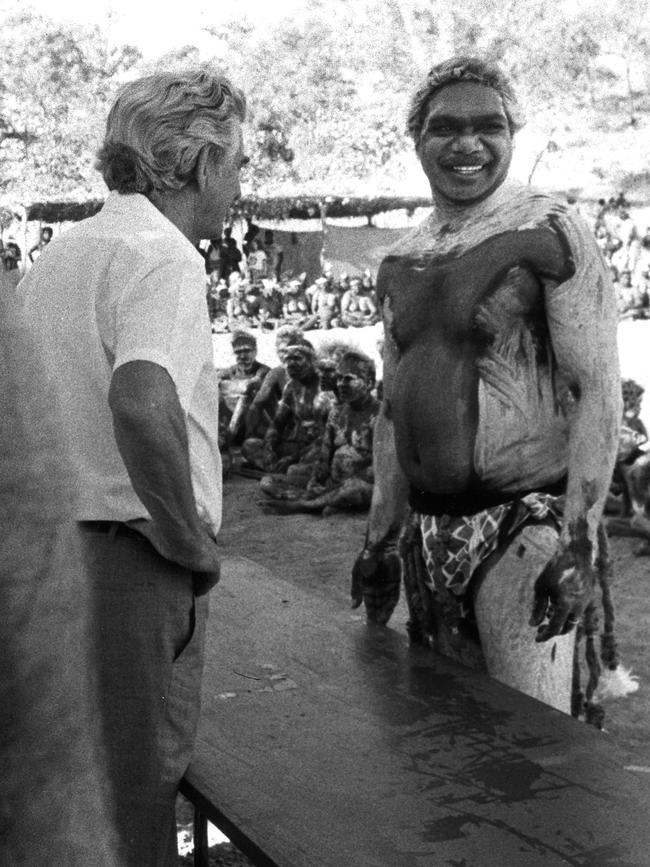

Yunupingu was still young but becoming a veteran already. Aged 15 in 1963, he had helped draft the Yirrkala bark petitions, a plea from the Yolngu to the Menzies government against the proposed bauxite mine on Yolngu land. When the Menzies government rejected those petitions, the Yolngu went to court. Yunupingu had recently returned from bible college in Brisbane and was the court interpreter for his people during the Gove land rights case in the NT Supreme Court that lasted from 1968 to 1971.

Chaney describes the hearings as like a university course for Australia. A voracious reader, Chaney goes back to the case often as a reminder of what truth telling looks like. The evidence, translated by Yunupingu for his old people, delivered one revelation after another.

“I don’t think there was any real comprehension outside academic circles about the depth of Aboriginal people’s connection to country,” Chaney says.

“This judgment actually put down on paper the nature of the relationship and why it needed to be recognised.”

The Yolngu lost because Australia was still bound by the Privy Council in Britain, which did not recognise land rights before colonisation. However, judge Richard Blackburn’s judgment acknowledged the existence and systemic practice of Yolngu law. This laid legal and political ground for seismic change.

It has long been known that Edward Woodward, the barrister for the Yolngu in that case, wrote to the Whitlam government urging that legislation was the way forward. What Chaney did not know until about 10 years ago was that the solicitor-general at the time, Bob Ellicott, who had represented the commonwealth in the Gove land rights case, did the same.

“I spoke to Bob years later and he told me that he had done that,” Chaney told Inquirer.

“So all the lawyers involved in the case were of the view that it might have been right in law but it was not right in principle.”

Yunupingu’s contribution in the years that followed was crucial.

In 1976, Malcolm Fraser finished the work that Gough Whitlam had begun by enacting the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act.

Yunupingu had advised on that legislation. He was courted by politicians and the National Press Club but was still living in Gove, where he passionately supported his Australian football team, Gopu, and was busy establishing a community for his immediate family away from the old Yirrkala mission at Gunyungara.

He was sharing the Gove Peninsula with non-Aboriginal workers with little or no first-hand knowledge of Indigenous Australia. My uncle Mark moved to Gove in 1981, aged 21, direct from Sydney’s west and a Catholic education that taught him Aboriginal Australians were dying and doomed. When Mark saw Yunupingu enjoying a midday beer alone in the front bar of the Walkabout Hotel at Gove, he felt an urge to speak to him.

“I told Yunupingu that the same Marist Brother that wheeled the TV into the classroom so we could watch Neil Armstrong step on the moon had told us that the Australian Aboriginal was a dying race. There would be no ‘full bloods’ by the year 2000,” Mark recalls.

“Yunupingu finished his beer, smiled and left without saying a word.”

This was Yolngu diplomacy.

Yolngu lived mostly at the former mission of Yirrkala then, a short drive from Nhulunbuy where the mine workers lived in mine-issued houses. The Yolngu were not yet involved in the enterprises that Yunupingu later championed, including a timber mill and bauxite mine, but they were independent and in charge of their community.

One of the Yirrkala village council’s employees at the time was Steve Fox, a recent graduate of teachers college in Adelaide who had arrived with his wife, Lil, to work as an arts adviser in 1979. Before long, he had quietly assigned himself a second unpaid job frustrating the evangelists who rolled into northeast Arnhem Land playing Pat Boone songs.

As the evangelists held a service at Yirrkala’s open-air church for Yolngu one morning, Fox was across the road painting the side of the arts centre in giant letters: “Be true to your (underlined) ancestors, they gave you your life and your land.”

I saw what Fox had done and I waited for the fallout.

But nothing happened as far as I could tell. The words stayed on the wall. The evangelists carried on, including by translating the Bible into the Gumatj language.

More than 40 years later, Fox recounts there was a showdown of sorts at the time but it was cordial and low key. It was a Yolngu lesson in how to live alongside those with whom you might disagree.

Fox recalls a conversation with the head of the Yirrkala Village Council, a senior Yolngu man who later became a Uniting Church minister.

“He said to me: ‘Steve, if you can’t just be a little more humble we might have to get you and your family a ticket home.’ So I was more humble after that,” Fox says.

Now 71, Fox looks back on his years working for the Yolngu with great happiness. He sourced the best carving tools he could find, taught printmaking to those who wanted to learn it and secured solo exhibitions for artists whose works are now at the National Museum of Australia.

Fox says the Yolngu made him feel valued and welcome and even invited him back for a second stint. More Yolngu diplomacy.

“They made it clear I wasn’t there to tell people what to do,” Fox says.

When my family left Gove in 1986, Yunupingu was one of the last people we saw. At the boat club the night before we flew out, he told us: “You will be back.”

I did return, but not until 2019 as The Australian’s Indigenous affairs correspondent. Yunupingu was hosting his 20th Garma Festival. He was an old man. Dressed in black with ceremonial headwear, he looked formidable.

This was a man who had been disappointed by a succession of prime ministers. He told the Morrison government to fix the Constitution or his people would throw it in the sea.

At his final Garma, in July last year, Yunupingu listened to Anthony Albanese promise a voice referendum and asked him: “Are you serious this time?” The Prime Minister told him: “Yes, we are going to do it.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout