Without leadership, Aboriginal policy will be owned by the far left

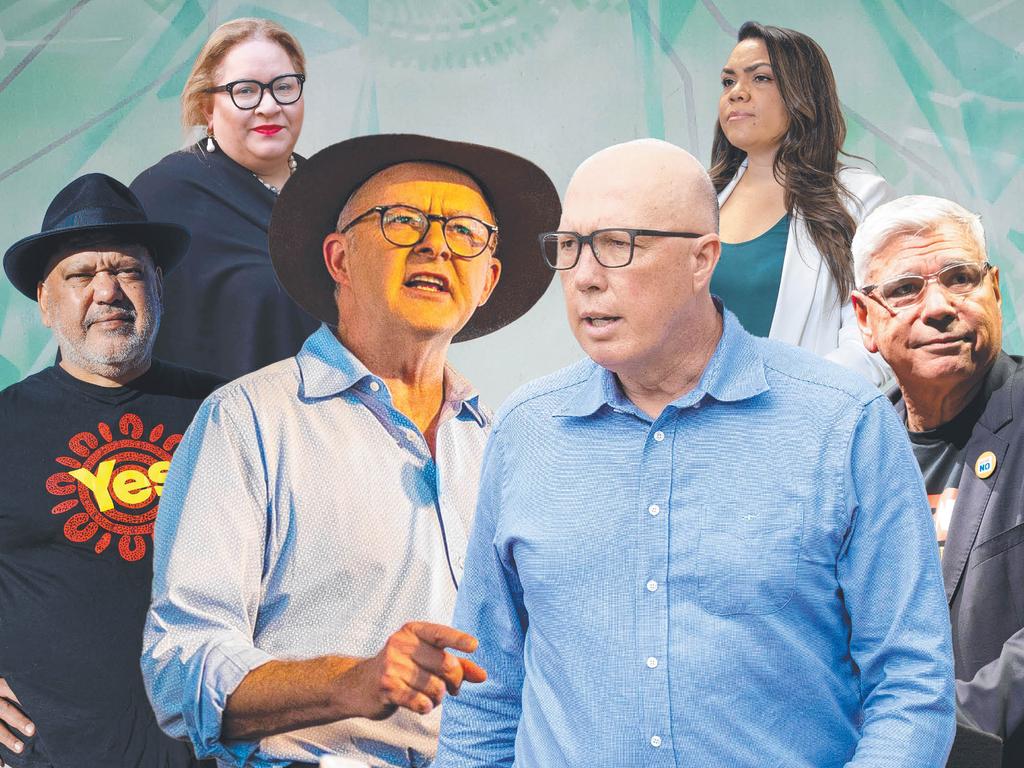

The direction of policy travel was highly dependent on the successful outcome of the referendum on constitutional recognition. Many eggs were placed in the pot of an Aboriginal voice. The comprehensive rejection of the referendum and, by implication, the Uluru Statement from the Heart, has left the federal government bureaucracy frozen and uncertain and the national Aboriginal leadership disappointed, angry, bitter and confused.

Much of the national Aboriginal leadership still clings to statements made by Anthony Albanese on election night in 2022 when that leadership should understand the raw politics of what the referendum did to those statements.

Australia has voted on a different direction and the Prime Minister should be released to develop a new agenda – and he needs to be confident to be bold in what that may look like.

This is difficult for Aboriginal Australia, as much was tied to the three elements of Uluru: voice, treaty, truth. I need to be blunt but certainly not disrespectful – those three words will not be part of the national Aboriginal affairs policy development in the coming decade. This is the politics of a failed referendum.

The great danger is that, without leadership from the mainstream political parties, Aboriginal policy gets owned and marginalised by the far left – attached to the strange, fringe politics of the unachievable.

I have spent three decades of my life fighting this marginalisation, and the drift of Aboriginal affairs back into the world of the far left – which seeks to define Aboriginality into permanent victims and therefore poverty – is extremely dangerous.

Similarly, the far right has no interest in claiming the space, there is no intellectual energy in even thinking about the Aboriginal question because Aboriginality itself is rejected. For the far right, Aboriginal history ended the moment the British flag arrived.

The danger of this drift is that it leaves victories that were hard-won across the previous decades vulnerable to attack and winding back; witness the increasing push against even those areas of previously settled common ground such as the welcome to country or validity of the Aboriginal flag as a flag of national identity.

Globally, the populations of democracies are impatient. Governments are changing at extremely fast rates and Australia is not immune to these changes. A combination of failure of policy, the embrace by the left of symbols, the harshness of identity politics and a rejection, in the name of the energy transition, of the many jobs people have worked in for generations threatens any community consensus around the globe’s response to climate change.

The nativism and macho approach from the right provides an avenue of escape for those who feel as though the left’s agenda does not include them – nay, is hostile to them. But the right may well find itself unable to deliver on the bargain and be subject to similar electoral volatility. To paraphrase Joan Didion, the centre is in danger of not holding at a time when it needs to not only hold but thrive, as it is from this base that Australia has created one of the most prosperous and successful nations on earth.

Aboriginal policy is perhaps the area of policy development most dependent on a strong and sustained centre. To the left lies ruin, to the right lies rejection.

There is still a broad bipartisan consensus on the importance of Closing the Gap and increasing the opportunities for economic development for Aboriginal Australians. Any reasonable Australian knows full well that we have created an enormously successful, wealthy and progressive nation that sits firmly in the centre of the political spectrum, sometimes slightly left and sometimes slightly right.

Every leap in the development of the relationship between Aboriginal Australia and non-Aboriginal Australia has been led from the centre – by the mainstream political parties.

In an age of bifurcation, how does the most marginalised part of our community navigate a way forward? How does a government develop an agenda that can broadly survive political swings?

It seems to me that the future of Aboriginal affairs is in the old well-worn path of economic development. And while this path has been well worn on a rhetorical level, it is in policymaking and implementation that the path has often faded.

The reality is that the failure of economic policy in some of our regional and remote areas is where the outcomes for Aboriginal Australians are at their worst, where the Closing the Gap outcomes are the most distant to mainstream.

This failure is not something that can be ignored as a remote figment of our national consciousness, for its outcomes appear again and again in our larger regional towns. When the recent Northern Territory and Queensland elections were fought largely on juvenile crime, what they really meant was Aboriginal crime.

But we should not be shocked by the criminal outcomes or the desire of communities to want a focus on crime – when economic development fails, when a marginalised people in a wealthy land do not see opportunities to participate in that wealth, then people drift from what they know into larger towns and do not become part of the society into which they drift.

Crime increases, people get scared and what is often lost on many is that Aboriginal people may well make up a disgracefully large part of those who commit the crimes, but also those who are on the receiving end of it. Aboriginal people vote for governments to provide a healthy, crime-free community as well.

If we focus on where the outcomes are at their most stark, we focus on regional and remote Australia. The failure in these parts of our country sweep through larger towns and cities and change governments. But we are, in the end, Australia, a country blessed with distance, space and resources. We know how to exploit and develop resource projects for national benefit – this is a skill that the far left maligns and this is why they hold nothing but failure in their offerings to Aboriginal Australia.

Regardless of its volatile trajectory, the world will continue its decarbonisation journey and Australia – regional and remote Australia – is central to success in this global journey.

Much of these new economic projects – critical minerals and renewable energy – will be in remote Australia, on Aboriginal titled lands. How does the nation combine the opportunity of the emerging economy with solving Indigenous impoverishment and social disorder?

The state government will always be key to service delivery. Closing the Gap is, in reality, a failure of state service delivery. There is more to be done here but the Coalition of Peaks and Closing the Gap needs to be reinforced as a service delivery agency – refocusing the National Indigenous Australians Agency on those key citizen rights issues, the failure of which means that there is no hope for Aboriginal people to participate in our economic success.

The states deliver these services much better than the federal government can, but the combined resources of the federal and state governments are needed to close those gaps in health and education.

The NIAA is spread hopelessly thin and, without a clear agenda, seems lost for purpose. Closing the Gap, co-ordinating federal funding with state service delivery, should be its focus.

When Australians voted in 1967, they voted for the federal government to be responsible for outcomes as a national commitment. To achieve these outcomes, there has to be an unprecedented collaboration between governments of the federation, Indigenous communities and industry.

And then there is economic development, the one area of Aboriginal policy that stands firmly in the centre and, therefore, has the broad support of Australians and its mainstream political parties. There must be greater collaboration between the governments of the federation, Indigenous communities and industry for Indigenous economic transformation.

While there is an existing architecture for this collaboration, what is missing is a framework for connections. That can happen only through national government leadership. The Prime Minister’s speech at Garma in 2024 shows that he sees this as the opportunity to move beyond the quagmire of the failed referendum – this is a hopeful position and the mid-year budget allocation of $17m to develop a First Nations economic framework is an enormous opportunity.

Despite its contentious beginning, the native title determination framework provides a system of Aboriginal development. Well recognised and generally accepted as the appropriate framework of representation, its great strength is that it provides a system of certainty about who to deal with, and credibility around striking agreements and sticking to them.

Undoubtedly, there is a real need for capability building and the federal government needs to take the lead here. The absence of Aboriginal leadership and capability in this space is perhaps the greatest risk the federal government has in achieving its aims – investment here will benefit Aboriginal people, Australian governments and taxpayers.

Importantly, it is not creating a new architecture but investing in the architecture that is the result of federal legislation.

Hand-in-hand with capability building is needed an aggressive means to invest. We need to create a national development fund through federal and state investment to rebuild Indigenous communities and generate economies that are sustainable.

The failure of communities is a failure of economies – you can’t have a successful community without opportunity, jobs, aspiration. This will require a style of investment that is more in the remit of our approach to foreign affairs in the Pacific, where capacity building is an important economic outcome in itself.

Breaking down the barriers for financing Indigenous economic opportunities; a national strategy to build Indigenous capacity; modernise agreements to support sustainable economies; reform the supporting institutions so they are fit for purpose – this is an agenda in urgent need of pursuit, more so in the anxious vacuum post the referendum.

This is Australia’s greatest unsolved challenge. It should be a national commitment. The referendum has becalmed an assertive Aboriginal affairs policy but it need not be the case.

The issues we need to fix are well known and now, with our nation’s resource riches and skills and a renewed embrace of what we do well in this country, combined with Aboriginal land, we have an opportunity to finally resolve the economic challenge of our nation’s most vulnerable people, once and for all.

Ben Wyatt is a former Labor treasurer for Western Australia, the first Indigenous treasurer for an Australian parliament, and is a director for Rio Tinto.

Right now it is almost impossible to predict how our nation may arrive at some form of consensus when it comes to Aboriginal affairs.