Northern Territory elections: Lia Finocchiaro and the Country Liberals inherit a wicked problem after defeating Labor

It is beyond a commonwealth bail out. The NT has a net debt $10.82bn. By contrast there is sheer panic in Tasmania over a $3.5bn debt on an island of 541,000 people. Keep in mind, Tasmania does not have the social problems that the NT has. Its residents are in relative good health. Tasmania has also got 12 senators advocating for its interests in the federal parliament, thanks to a requirement in the constitution that gives every state 12 senators regardless of population and size. The top end has just two senators. And the hard work facing Ms Finocchiaro is unique Australia-wide because 30.8 per cent of NT residents are Indigenous. The Australian’s health editor Natasha Robinson has shown us in eye-opening reports why this matters. Central Australia is a global diabetes capital. NT hospitals are overwhelmed with diabetes admissions and required amputations on younger and younger Indigenous people. In the northwest corner of the NT in Arnhem Land, men die – on average – aged 54. All manner of chronic and preventable illnesses hit the top end’s Indigenous residents at shocking rates.

In responding to violence, alcohol-fuelled chaos and family dysfunction in Alice Springs earlier this year, Anthony Albanese called these “complex problems”. These are also expensive problems.

Eva Lawler, the Chief Minister since only December last year, has said: “It is hard slogging work to address a young person that is committing a crime”. She is not wrong. The evidence is in that keeping disadvantaged children on the right path is possible but it is a lot of work. A custodial sentence when they are 16 does nothing but protect the community they have harmed. Preventing the tragedy of a life of crime and blunted potential starts with pre-natal programs that support pregnant women to make good choices. Early childhood programs are crucial to get children ready for school. Intensive early interventions when families are struggling needs to be done properly, and by people who know what they’re doing and who they are dealing with. It all costs a lot. It does not, however, cost as much as dealing with the consequences of inaction.

As opposition Indigenous affairs minister Jacinta Nampijinpa Price told the Sky News panel on Saturday night: “We can decrease incarceration by dealing with the problem when they’re children.”

The financial crisis in the NT is beyond anything a commonwealth bailout can fix.

It is based on historical deficits. For example, when the Commonwealth left the NT to self government in 1978, the basics were not in place. Arterial road networks, power and water systems and other infrastructure were re-established in Darwin after Cyclone Tracy but they were sparse and non-existent elsewhere.

However, the NT has not managed its Commonwealth grants well for many years. This is partly because the seats that both sides of politics need to get re-elected are in Darwin. So are most of the public servants who administer those grants. It is partly because the NT’s population is dispersed and it is not cheap to deliver services to very remote areas – a one way flight from Darwin to Borroloola is $947. However, successive NT government’s have refused to slash what the Yothu Yindi Foundation calls “an administrative class” of bureaucrats.

Five years ago, economist John Langoulant told the NT government it must demote 300 NT government executives who were earning $217,533 to $233,565 a year. Langoulant, the former WA under-treasurer, found the NT executives had “the same work value” as senior bureaucrats earning $155,915 to $169,788 and therefore should be paid the same as them. The NT government did not accept this recommendation.

The Yothu Yindi Foundation’s then accountant, Barry Hansen, had analysed spending patterns and formulas through Commonwealth Grants Commission data, NT and federal budget reports and audits. In a 13-year period, he found the NT’s population had increased 21 per cent but the number of public servants had grown by 41 per cent. Hansen told the Productivity Commission an extra $500m in GST revenue allocated to the NT to take into account its disadvantaged remote Indigenous population was not spent directly on services for Aboriginal people.

At the same time, the NT government spent $300m on a bar and dining precinct on the Darwin waterfront.

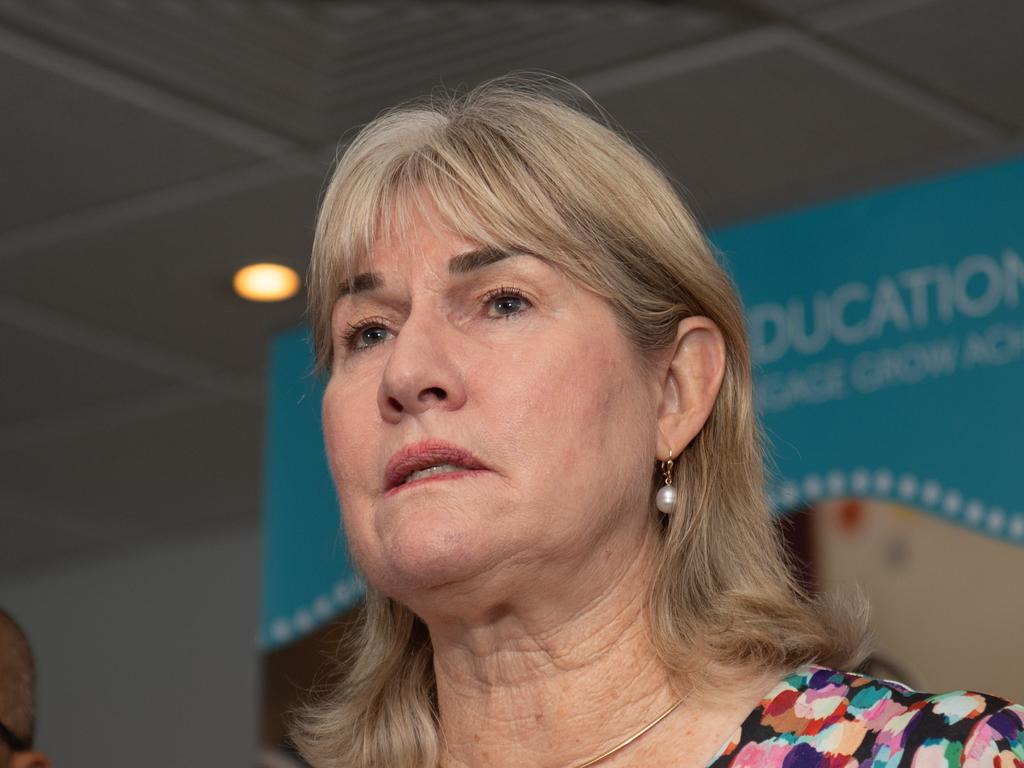

The Northern Territory government’s most high-profile challenge is crime but behind the scenes the deeper crisis is debt. Lia Finocchiaro is poised to inherit a wicked problem decades in the making. Her ability to address the crime and social dysfunction in Alice Springs and beyond is severely impaired by the fact the territory of 233,000 people is a financial basket case.