Social media sums on Indigenous spending do not stack up

Wild claims on social media about the size of government largesse toward Indigenous Australians do not stack up.

Denise Bowden, a Tagalak woman from Katherine, was at the shower block one evening at the Garma Festival in northeast Arnhem Land when the power went out. There was a burst of protest from city guests suddenly washing in the dark. “I mean no harm but I must confess I thought: ‘Welcome to the bush,’ ” Bowden said later in her speech to a mostly non-Indigenous audience.

“In the places where Aboriginal people live in remote Australia we lack the basics that are taken for granted by the rest of Australia – if it’s not health facilities, it’s housing support. If it’s not the power, it’s the sewerage. If it’s not the absence of a decent road, it’s the lack of a proper school, or a safe place for old people.”

This reality would seem to be at odds with some of the big, loose numbers flying around on social media about what Indigenous Australians receive from the government. But the available figures are not what they first seem.

The genesis for some of the claims about government largesse is the Productivity Commission’s 2017 Indigenous Expenditure Report, the most recent of its kind. It is an estimate of the levels of federal, state and territory government expenditure on services relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It is based on spending in 2015-16.

That year, total federal, state and territory government expenditure (for all Australians) was $556.1bn. The report apportioned $33.4bn of that to ATSI people. That means it apportioned 6 per cent of total expenditure to Indigenous Australians, who at that time comprised a little more than 3 per cent of the population.

However, the Productivity Commission says the $33.4bn figure cannot be presented accurately as Indigenous-specific spending. Most of it is for services all Australians share. For example, it includes a portion of Australia’s foreign aid budget and of what it costs Australia to take refugees.

The Productivity Commission estimates that, of that $33.4bn apportioned to Indigenous people, $6bn, or 18 per cent, was for Indigenous-specific services. The remaining $27.4bn was indirect spending; Indigenous people’s share of mainstream services and programs such as Medicare, school and aged care. It included a portion of the defence budget. So, overall, 1.1 per cent of the $556.1bn that all governments spent on all Australians that year was “targeted expenditure understood to be exclusively for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people”.

In 2015-16, estimated expenditure per Indigenous Australian was $44,886, twice that for non-Indigenous Australians ($22,356). The difference has been attributed to factors including “greater intensity of service use” because of greater need, because the Indigenous population includes more babies and school-aged children than the general population and the higher cost of providing services to remote locations.

These Indigenous Expenditure Reports – once annual – are not a verdict on money well spent or wasted. “The IER does not assess the adequacy, effectiveness, and efficiency of government expenditure,” Productivity Commission acting chairman Alex Robson tells Inquirer. “In addition, the IER expenditure figures do not show which people and organisations received funding to deliver government programs, or the location of where money was spent (other than the state or territory).”

The lack of detail in the reports sometimes has led to assumptions that do not add up. Those familiar with Indigenous policy know most money apportioned to ATSI people in government reports goes to departments and agencies that spend it on projects of their choosing. The totals diminish at every step. For example, it costs 6c to 12c for a dollar to leave the federal government’s coffers and arrive in the account of a state or territory government. That is not the cost of administering a program; that is the administration cost to get money out the door of one Treasury department to another.

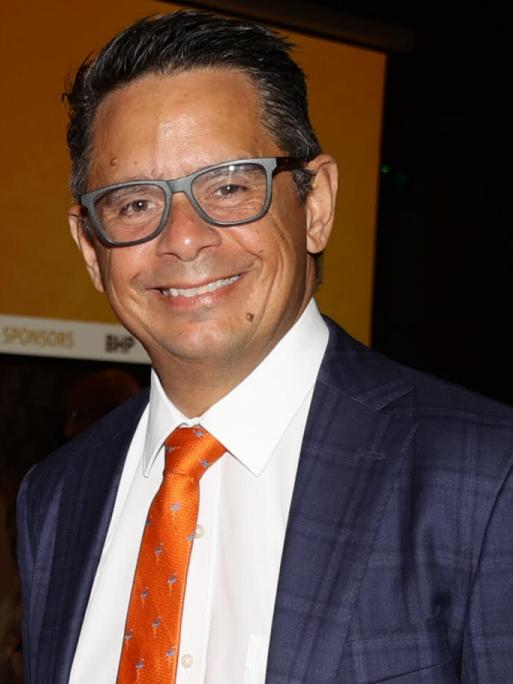

Lowitja Institute chairman Selwyn Button was prompted to publish a plain-language summary of spending in Indigenous affairs because of misinformation throughout the voice debate.

He says even slight improvements in the efficiency of the federal government’s existing spend on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wellbeing would generate substantial savings. That is where the Lowitja Institute, a health research body, believes the voice can help. The institute knows what we are doing is not working. It found federal expenditure on Indigenous-specific functions had doubled in the past 15 years but outcomes had not improved at a corresponding rate.

There are alternatives. When the Mater Hospital in Brisbane partnered with two community-controlled Indigenous health organisations to reduce the number of Indigenous babies born prematurely, the result was an effective program delivered by Indigenous health workers. The preterm birthrate for Indigenous babies at the Mater fell and now is almost the same as the non-Indigenous preterm birthrate. The saving is $4810 per mother and baby.

Modelling by the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health estimated that replicating the Mater program across the country could reduce the number of ATSI babies born preterm each year by almost 1000, thereby leading to long-term health expenditure savings of more than $86m.

In the past five years, successive federal governments have announced more than $2.7bn in new money towards Closing the Gap initiatives, but the latest data shows most key outcomes for Indigenous people are not on track and in some areas are getting worse. The recast Closing the Gap agreement is a promise from governments to work with Indigenous communities as the Mater has done, but the latest Productivity Commission report shows that is not happening.

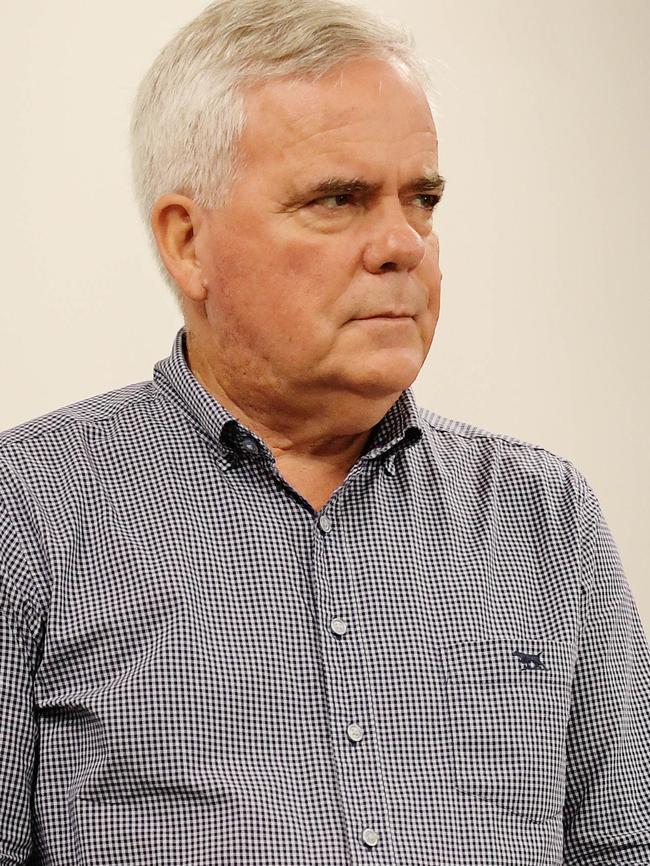

Former West Australian treasurer Ben Wyatt, an Indigenous man, offers an explanation. In a recent essay in The West Australian, Wyatt said there was a fear of failure in Indigenous policy that meant governments were reluctant to upset the status quo.

“Although motivated by goodwill and the understanding that they needed to engage Aboriginal people, bureaucrats within government were often clumsy, wandering around in the policy dark as to who to engage, how to engage and what advice to accept,” Wyatt wrote. He argued the voice would give certainty about who to consult and direction about the changes to be made.

This is what Cape York Institute founder Noel Pearson means when he talks about the right to take responsibility. He says Australia must reach a point in its relationship with Indigenous people “where it is legitimate to blame us”.

Wyatt continues: “The voice is the only thing on the horizon that presents some accountability to this abysmal failure of public investment in improving the lives of Aboriginal people.”

By contrast, Bowden’s speech at Gulkula four years ago made it clear the Yolngu people were observers, not architects, of the maladministration and incompetence that ruled their lives, She relayed the story of elder Mrs Gurruwiwi, who died waiting for aged care on Yolngu land. “I sat in a meeting in 2014 as Mrs Gurruwiwi pleaded with senior public servants to build such a facility with money that was already appropriated,” Bowden said. “She died a few years later in a hovel that was not fit for human habitation.”

Bowden, chief executive of the Yothu Yindi Foundation that hosts the annual Garma Festival, spoke as the Northern Territory government considered a grim report from economist John Langoulant that backed everything she said about its bloated and ineffective administration. He found the NT faced an interest bill of $2bn a year by 2030 and “requires comprehensive cultural change”.

His recommendations included demoting 300 NT government executives who were earning $217,533 to $233,565 a year. Langoulant, the former WA under-treasurer, found the NT executives had “the same work value” as senior bureaucrats earning $155,915 to $169,788 and therefore should be paid the same as them. The NT government did not accept this recommendation.

The Yothu Yindi Foundation’s then accountant, Barry Hansen, had analysed spending patterns and formulas through Commonwealth Grants Commission data, NT and federal budget reports and audits. In a 13-year period, he found the NT’s population had increased 21 per cent but the number of public servants had grown by 41 per cent. Hansen told the Productivity Commission an extra $500m in GST revenue allocated to the NT to take into account its disadvantaged remote Indigenous population was not spent directly on services for Aboriginal people.

At the same time, the NT government spent $300m on a bar and dining precinct on the Darwin waterfront.

“This work confirms everything we see in front of us and explains why many Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory continue to live impoverished lives,” Bowden said.

“The data shows time and time again that hundreds of millions of dollars of untied GST funds sent to state and territory governments to address Aboriginal issues are diverted to other urban priorities, or are spent on administration in Darwin or other urban centres.”

In the years since the Productivity Commission report was published, some details have emerged about funds earmarked for the benefit of Indigenous people being used for other things.

In 2018, then federal Indigenous affairs minister Nigel Scullion told Senate estimates he gave almost $500,000 from the Indigenous Advancement Strategy to help fishing and cattle groups fight Indigenous land claims.

Indigenous leaders see the $4.9bn IAS as emblematic of the problem in Indigenous policy. Uluru Dialogue member Eddie Synot said last month: “Many highly ranked community programs were rejected in favour of lowly ranked applications hand-picked by the minister and PM, while over 300 applications from vital community services were lost with no reasons given.” As an example, he said Indigenous entrepreneur Nyunggai Warren Mundine received $330,000 from the IAS for his Sky News program Mundine Means Business “while our communities went without programs to support community safety, get kids to school or our people into jobs”.

In her Quarterly Essay published in June, one of the Uluru Statement from the Heart’s architects, Megan Davis, calls Tony Abbott’s decision to introduce the IAS “a primary driver” of the call for a voice. “This policy saw $534m stripped from the Indigenous Affairs budget … there was no review of programs and activities to determine what worked and what did not work,” Davis wrote.

“Overnight, communities were disrupted by this extraordinary piece of policy that took a razor to programs that had been run for decades, including men’s groups and the award-winning women’s night patrols that protect women and children from violence.”

The Australian National Audit Office’s assessment of the first full year of that program found a litany of failings including poor record keeping, performance targets were not set for all the funded projects and a grants process that “fell short of the standard required to effectively manage a billion dollars of commonwealth resources”.

This is not a shock to Davis, who has been reading audits of state, territory and commonwealth projects in Indigenous affairs for 20 years.

“We need to explain to Australians why the voice is needed,” she wrote. “Indigenous policy issues are alien to most and the loudest voices on the subject are often the politicians who were most ineffective in this policy area.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout