Treaty architect Percy Spender ‘thought ANZUS was a great win for Australia’

The alliance with the US was Percy Spender’s crowning achievement, his son John says.

John Spender, his son and a future Liberal MP (1980-90) and ambassador to France (1996-2000), was 15 at the time. He lived at the ambassadorial residence, a brick mansion known as White Oaks, during his father’s tenure in Washington DC.

“The ANZUS Treaty meant a great deal to my father,” Spender, 85, recalls in an interview with Inquirer. “He was very proud of it. He thought that it was a great win for Australia and for democracy generally.”

John Foster Dulles led negotiations on behalf of the US. Dulles had advised Republican Thomas Dewey in his presidential campaigns against Democrats Franklin Roosevelt in 1944 and Harry Truman in 1948. But Truman appointed Dulles as a special adviser and to negotiate peace and security treaties with Japan, which also were signed in September 1951.

“My father had a great capacity to understand people and to make friends,” Spender says. “He made a close friend of Dulles, who later became secretary of state. When my father was ambassador to Washington, Dulles and his wife used to come by occasionally to have a casual evening meal with my father, my mother, and myself.”

This relationship was of great benefit to Australia when Dulles was appointed to head the State Department by president Dwight Eisenhower in 1953. Percy Spender served as ambassador from 1951 to 1958, having previously been minister for external affairs from 1949 to 1951.

“It was of enormous importance to have that kind of access at that level, which is something that people frequently overlook,” John Spender notes. “The personal relationships can make a great difference to the way in which things are done.”

It was also critical to convince Truman to support an ANZUS Treaty. John Curtin had raised Pacific security arrangements with Roosevelt as a necessary “insurance against future aggression” in 1944 and Ben Chifley did the same with Truman in 1945. But these talks were a long way from an ANZUS Treaty.

Spender saw Truman’s role as “crucial” and “doubted” whether a treaty could have been signed without his encouragement. The upshot of the first Spender-Truman meeting in 1950 was that negotiations with the State Department had the president’s support.

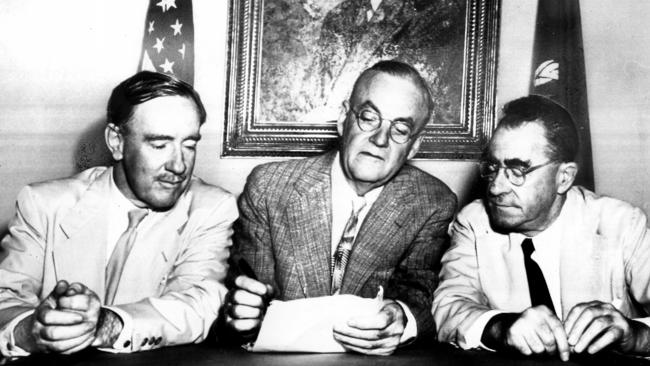

There were four American signatories to the treaty – Dulles, secretary of state Dean Acheson, Republican senator Alexander Wiley, Democratic senator John Sparkman – and New Zealand’s ambassador, Carl Berendsen.

The preamble stated that “no potential aggressor could be under the illusion that any of them stand alone in the Pacific” and made a joint commitment to “collective defence for the preservation of peace and security” in the region.

The wording of the treaty was, and remains, somewhat vague about the conditions in which either country would come to the aid of the other and what form it would take. Article II notes that the parties “separately and jointly by means of continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid will maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack”.

Article IV “recognises that an armed attack in the Pacific area on any of the parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes”.

It is not an unconditional security guarantee and there is no automatic requirement for either party to respond. It is non-binding. But the wording would surely make it impossible for the US to ignore a request for Australian assistance if imperilled. It also acts as a deterrent to any potential aggression towards Australia.

The treaty also provided a framework for managing and developing the alliance in future years via the establishment of a “council”. This gave Australia a capacity to influence the US and the opportunity to be consulted.

Robert Menzies regarded the ANZUS Treaty as the seminal achievement of his government. But initially he was not enthusiastic and doubted it could be achieved. Menzies played no substantial role in negotiations and was not present at the signing. Nor was external affairs minister Richard Casey.

In his memoir, Exercises in Diplomacy (1969), Percy Spender wrote that Menzies’ view was that “Australia did not need a pact with the USA since she was already overwhelmingly friendly to us and Australia could rely on her”.

Percy Spender disagreed. “He had a very clear view of the world as a place that could go very, very bad, as happened to us when Japan declared war and ‘Mother Britain’ wasn’t able to come to our help,” his son says.

“The plain facts of the matter were that Britain would never again be a world power and that we needed to have a ‘backer’, you might say. It was obvious to my father that the 20th century was America’s and that Australia needed to have America as our backer in the event that there was an outbreak of hostilities.”

The British government was not happy about being excluded from ANZUS. Prime minister Clement Attlee was furious. So was opposition leader Winston Churchill. In my biography of Menzies, I revealed that Churchill scolded Menzies after his return to the prime ministership. “You know, we take a rather poor view of this,” Churchill said. “Aren’t we in these things?”

There was sympathy for the Attlee-Churchill view within Labor at the time, led by HV “Doc” Evatt. But Menzies argued, correctly, that the UK had joined NATO, which did not include Australia. Australia had to look after its own interests in its own region. The UK, however, was included in the Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation, which was designed to be a collective defence arrangement for the region. It was signed in 1954 and dissolved in 1977.

While Menzies and Spender generally got on well, they had disagreements from time to time. Menzies was unenthusiastic about another Spender initiative: the Colombo Plan. Menzies had a streak of jealousy, perhaps insecurity, and his staff and colleagues recall that he criticised people out of earshot. There is no doubt that Menzies also saw Spender as a rival.

In a series of interviews with Frances McNicoll for a biography that was never completed, Menzies referred to Spender as “little Percy” who was “a lawyer of the second order” with grand ideas that gained him much publicity. “His ambition was, of course, overwhelming,” Menzies said of Spender. Nevertheless, Menzies regarded Spender as a good ambassador.

John Spender acknowledges that his father would have liked to be prime minister. “But my father never thought of challenging Menzies; that wasn’t his nature,” he argues. “He saw Menzies as someone who would stay PM for a long time. After the ANZUS Treaty was agreed to, in early 1951, he decided to leave politics.”

It is unlikely there would be an ANZUS Treaty, which cemented the Australia-US alliance, without Percy Spender. He was an intelligent, shrewd and convincing negotiator. He understood the shifting power balance in global affairs. And he identified Australia’s needs and seized opportunities others missed.

“I don’t think there is anybody else who had my father’s determination to conclude such a treaty,” his son suggests. “He had enormous capabilities of persuasion. He was determined to make it for Australia. He had great energy. There was simply no one else around the Australian table who would have been able to pull it off.”

The ANZUS Treaty is a gift from history. It is the keystone of Australia’s foreign policy and security, and underpins our most important bilateral relationship. It is near certain that the US would not sign the ANZUS Treaty today.

“My father believed in America and he believed in the future of America,” recalls Spender. “He liked its energy, dynamism and its readiness to try things. Things have changed greatly since then and I don’t think there would be a snowball’s chance in hell of having a treaty such as ANZUS with America these days.”

So, what would Percy Spender make of the ANZUS Treaty seven decades after it was signed?

“My father would be very proud of the fact that the ANZUS Treaty, 70 years on, is alive and strong,” John Spender says. “He would be very concerned about the state of the world because he was somebody who saw the world as it is, not as we would like to see it. I think he would look upon the ANZUS Treaty as something that we should use, not just as a backstop, but we should use the apparatus that we have set up as a means of influencing American opinion at the highest level as much as we can.”

Troy Bramston is the author of Robert Menzies: The Art of Politics (Scribe)

When the ANZUS Treaty was signed 70 years ago at the Presidio overlooking San Francisco Bay on September 1, 1951, there was only one Australian signatory: Percy Spender. Spender, then Australia’s ambassador to the US, was the principal architect of the treaty. He devised it and led negotiations with the US and New Zealand as minister for external affairs in the Menzies government. It was the crowning achievement in his long contribution to public life.