ANZUS Treaty: Australia’s US military alliance stands test of time

The key to the ANZUS Treaty’s longevity has been strategic reinvention.

The ANZUS Treaty has survived 14 US presidents, 14 Australian prime ministers, a transformed world from the Cold War to Islamist terrorism to the rise of China. It has survived victories, defeats, Australian anxiety and US indifference but has been bonded by the interests of both nations and astute leaderships at times of crisis.

The alliance is now surrounded by a fog of sentimentality created by its champions – the latest being “100 years of mateship” – that makes separating reality from mythology near impossible. Indeed, one wonders whether today’s politicians can navigate between its celebratory legend and its governing realpolitik. In truth, the Trump-Biden era injects a new uncertainty into alliance management.

There was nothing inevitable about the ANZUS Treaty. Yet the treaty has changed Australia as a country, strategically and culturally. Despite its uneven record, ANZUS has been to Australia’s immeasurable benefit, while not every decision under the treaty’s influence has been justified or necessary.

One of the alliance’s eminent historians, Peter Edwards, reminds Inquirer of the immortal comment in 1942 when US general Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander of Allied forces in the southwest Pacific, told Labor prime minister, John Curtin the US saw Australia solely “as a base from which to hit Japan”. Rather than looking to America, if Australians wanted anything more they should look to Britain and its ties “of blood, sentiment and allegiance to the crown”.

MacArthur’s message was blunt: Australia was convenient to the US in World War II but that time would pass. And it did pass. Post-war, there was no American interest in a military treaty with Australia. Post 1945 there was neither sentiment nor strategic logic for it.

So how did ANZUS originate?

It originated as an Australian initiative. It sprang from Australian anxiety and ambition, a useful chemistry in our history. If left to the US, there would have been no treaty. To an extraordinary extent, the treaty was the achievement of one man, foreign minister Percy Spender, appointed by Robert Menzies after the Coalition’s 1949 election victory. It was Spender’s vision, drive and opportunistic brilliance that secured ANZUS.

This is an asymmetrical alliance. Australia as the junior partner has been the innovator, the decisive eras being that of Hawke-Reagan and Howard-Bush. Every new Australian prime minister cogitates on how to add value to the alliance. The key to the treaty’s longevity has been strategic reinvention. A treaty denied nourishment will surely die.

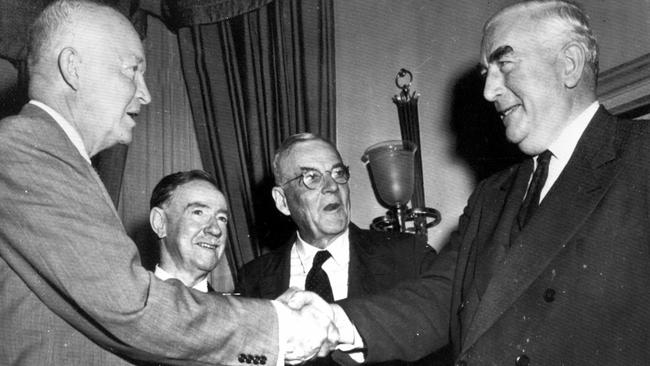

Menzies, the inaugural prime minister, began as a sceptic. In 1950 he had branded the idea as “a superstructure on a foundation of jelly” – a view that left Spender incredulous. When Spender’s negotiations in Canberra with US envoy John Foster Dulles were completed on the afternoon of Sunday, February 18, 1951, he went to the Lodge. Menzies asked Spender what had happened.

Spender produced from his pocket the draft treaty and said: “Read this.” As Menzies read, Spender noted his surprise and satisfaction. “Good work, Percy,” Menzies said. “Come and have a brandy.” Spender said that may have become two brandies.

But neither could have imagined the edifice over 70 years that would be built on the treaty. It has been the most enduring “jelly” in Australian history. Menzies, on his retirement, nominated ANZUS as one of his government’s greatest achievements.

Driven by Cold War

ANZUS was a creation of the Cold War, not World War II. Ironically, the 1949 Communist Revolution in China was pivotal. During 1949-50 China went communist, North Korea attacked South Korea and China entered the war. It was the transformed politics of North Asia that led to ANZUS.

Australia’s decision to enter the Korean War was driven by Spender when Menzies was on board the Queen Mary sailing from Britain to the US without secure communications. It was Spender who, in a famous phone call with acting prime minister “Artie” Fadden, browbeat Fadden into agreeing to an Australian war commitment to Korea.

Fadden, fearful of the “Big Fellow”, wanted to wait until Menzies reached New York. Spender rejected this. “You must take the decision now,” he told Fadden, battering him into submission.

For Spender, this was all about a future treaty with the US. Knowing the British government was about to commit to Korea, he was determined to get an Australia commitment first as proof to the US of Australian independence.

Spender’s convictions sprang heavily from Australia’s war experience. A barrister who had served as treasurer and army minister and then on the War Advisory Council, he had ambitious views on foreign and defence policy. Spender believed post-war Australia must reorient to the US, that it needed a formal Pacific pact to anchor its interests and that it must have access to the high councils of allied decision-making to avoid being patronised as a lap-dog. He was a man ahead of his time.

With little enthusiasm in the Truman administration for his initiative, Spender had a fateful meeting in the Oval Office with Harry Truman on September 13, 1950, for what was supposed to be a brief formal call. Given Australia’s commitment in Korea, Truman was well disposed.

Spender apologised for introducing a policy matter into a formal call but began by telling the president despite Australia’s role in two world wars the nation had no access to machinery “for determining global strategy”. He told Truman Australia was “entitled to a voice” in shaping the future of the Pacific.

His hope was for a new trans-Pacific regional security arrangement. Spender said any such pact would be meaningless without the US. Should another war break out, Australians would be dying in the Pacific and Australia was entitled to a say in how events would be determined. Truman sympathised with Spender’s argument. He then expressed his admiration for the Australian soldiers he had got to know during World War I. Truman told Spender he would ask secretary of state Dean Acheson to give further consideration to Spender’s case.

“When I left his room, for the first time I felt that I had found someone outside Australia who thought the ideas I was canvassing had some merit,” Spender wrote. He believed this meeting with Truman was crucial. Australia’s official historian, Bob O’Neill said: “There can be no doubt that this conversation was the real turning point which led to the ANZUS Treaty.”

On September 22 Spender had a vital meeting with Dulles, who had US responsibility for negotiating the Japan peace agreement. Herein lay the instrument Spender would use to secure ANZUS.

Dulles made clear the US wanted a “soft” peace agreement with Japan – it needed to recruit Japan on its side for the Cold War in Asia. Spender told Dulles “in very blunt terms” Australia would never tolerate a soft treaty that left open a potential resurgence of Japan’s militarism.

Spender saw a strong bargaining position opening for Australia. He said Australia would not accept the Japan peace treaty Dulles was contemplating without some form of security guarantee for Australia. Spender told Dulles he had been arguing for a Pacific pact but was making “no headway at all” and, in this situation, the US must offer Australia a form of protection.

Dulles was open to this negotiation. In February 1951 Dulles visited Australia for talks involving three parties: the US, Australia and New Zealand. The Menzies cabinet was not optimistic, its sentiment being that Australia might need to settle for a mere “presidential declaration”. But Spender pushed hard and got his treaty.

A global partnership

Signed in San Francisco on September 1, ANZUS has 11 short articles. Unsurprisingly, Spender failed to win the stronger security guarantee of the NATO Treaty.

Yet the words are more significant than many assume, saying an armed attack on any party or its armed forces means parties “would act to meet the common danger” in accordance with their constitutional process.

Dulles told MacArthur the US could meet its legal obligations under ANZUS “in any way and in any area that it sees fit”. For Australia, there was a dual legacy – triumph and anxiety. Having got the treaty, the constant refrain became: can we rely on America? For years Australians politicians fretted: would the US back Australia in conflict with Jakarta?

Across time Australia came to realise what mattered was not the words but the partnership. Eventually, mainly due to Australian initiatives, ANZUS was turned into a political institution. It became a framework with its own legitimacy via military dialogue, intelligence co-operation, defence procurement, force interoperability, joint facilities, two-way finance and investment, and a network of people-to-people links.

Rarely has a narrow security treaty bequeathed such an edifice running in tandem with the growth in US-Australian ties. The political legacy of ANZUS has facilitated a new strategic and cultural mindset in Australia. Twenty years ago veteran US diplomat Richard Haass described the alliance as “two countries joined in a global partnership”, a vision far beyond that of its 1951 architects.

In hindsight, the 1951 treaty was the perfect innovation for its age. It meant Australia for the first time was involved in a military pact that excluded Britain, a departure from the post-1788 military frame. The new senior partner was not tied to Australia by empire, crown or kinship. We had to prove our worth.

A sullen Britain did not seek membership of ANZUS. But Winston Churchill was unhappy and attacked the British Labour government for its alleged failures.

“We were asserting ourselves in a new role,” Spender said. “We were definitely no longer just a colonial dominion.”

The treaty envisaged Australia fighting in wars without Britain and this happened the next decade in Vietnam. Yet the treaty did not immediately substitute the US for the UK. Menzies was astute in playing both the US and Britain as “great and powerful” friends as Australia’s military commitments in the 1950s and ’60s were to the Malayan Emergency and resisting Indonesian Confrontation, and that involved fighting with British Commonwealth forces.

The treaty testified to Australia’s future as a Pacific and Asian power. The US alliance brought Australia more deeply into the strategic struggles within the Asia-Pacific – its protection helped to underpin a new relationship with Japan, culminating with the 1957 Australia-Japan Commerce Treaty, while the alliance became pivotal to Australia’s security tensions with president Sukarno’s Indonesia and communist insurgency in Southeast Asia.

Fundamental to domestic support for ANZUS is that the Labor and Liberal parties both claim its ownership. This paradoxical situation has entrenched support for the US alliance in Australian politics. It is still on display today.

Labor mythology holds that Curtin’s “look to America” appeal of December 1941 is the real foundation of the alliance while the Liberals know the treaty was negotiated by the Menzies government and have compulsively sought to exploit their alliance loyalty for domestic political purposes for much of the 70 years.

The treaty is based on mutual obligation, a fact most Australians missed until the al-Qa’ida attack on the US on September 11, 2001. The security obligations are shared. ANZUS is no one-way street. Many Australians were surprised to find the treaty invoked for the first time because of an attack on America, not Australia.

ANZUS faced its gravest crisis during the Whitlam-Nixon period when a paranoid US president dealt with an immature Whitlam government, with its ministers venting their hostility to the US over Vietnam. Edwards said this caused the alliance “to be questioned at the highest levels in Washington”. Historian James Curran said Gough Whitlam, however, eventually demonstrated to a complacent White House the ability an Australian leader possessed to seek a “less adulatory” dynamic within the alliance.

The most creative recasting of ANZUS came under Bob Hawke operating with Republican president Ronald Reagan. The changes in the Hawke-Reagan era became basic to the alliance’s endurance. Hawke, supported by foreign ministers Bill Hayden and defence minister Kim Beazley, put a Labor stamp on the alliance when it was being questioned within ALP circles. This was a period of intense stress on ANZUS. Reagan was confronting the Soviet Union; New Zealand terminated the treaty’s tripartite nature; the Labor government, acting on Richard Nixon’s Guam Doctrine, adopted a policy of defence self-reliance; and Hawke and Beazley redefined the joint facilities as means to advance Labor’s aims of deterrence and conflict avoidance.

After the confusion of the Whitlam period Hawke presented the alliance as an instrument to achieve not just national interest objectives but long-run Labor aspirations and values. In truth, Labor’s contemporary support for the alliance really stems from the Hawke era while paying lip service to Curtin and Whitlam.

Bonds of 9/11

Edwards calls Hawke the “most astute” alliance manager in the list of Australian prime ministers. He won the trust of the Reagan administration and that of George HW Bush, and invested the alliance with a new acceptance on the centre-left of politics.

Edwards said Paul Keating followed in this vein, his unique contribution being in the realm of ideas – Keating presented Bill Clinton with fresh ideas, notably the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation forum’s leaders meeting. He sought a new integration between the alliance and Asian engagement, saying Australia got its security “in Asia, not from Asia”.

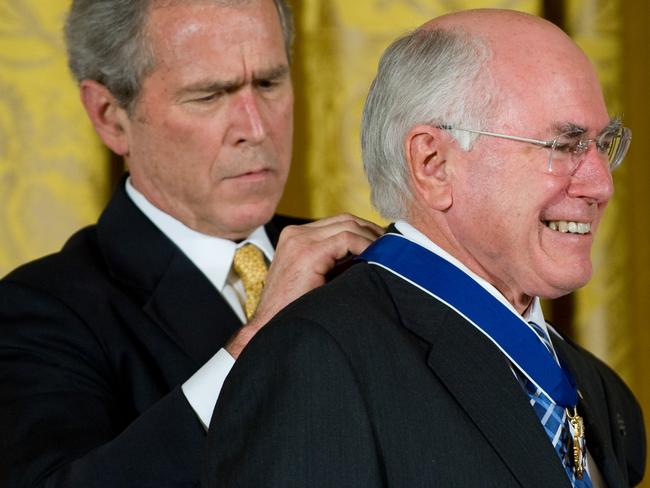

The closest personal bond in the history of ANZUS was between John Howard and George W. Bush. Being in Washington at the time of the 9/11 attack, Howard took the alliance into new dimensions of trust, shared values and national empathy. “Of course, it’s an attack on all of us,” Howard said the next day. Sensing America’s vulnerability, he offered an open-ended pledge of support, and this is the origin of Australia’s war commitments in Afghanistan and Iraq. For Howard, the existential moment determined these decisions. “There’s no point in a situation like this being an 80 per cent ally,” he said.

Yet Howard’s pragmatism never deserted him; the highly criticised Iraq war commitment saw Australia win Bush’s eternal gratitude at a minimum cost of Australian lives. Iraq raised the question: did Australia need to fight with the US in every war? Edwards said it didn’t. He said “we could have and should have” avoided the Iraq war commitment. The alliance would have survived this restraint. Yet there is no gainsaying the Howard-Bush bond generated a major expansion in the alliance partnership – in military co-operation, interoperability, intelligence and a free-trade agreement – all duly endorsed in the Rudd-Gillard era.

The Trump-Biden era sees US foreign policy driven by populist appeals to Middle America creating a new uncertainty. Donald Trump attacked the US alliance system. Joe Biden promises to restore it. But how serious is he?

Asked if this situation could threaten the viability of the treaty, Edwards said: “It certainly has that potential and questioning of the value of allies won’t go away in a hurry.”

For 70 years both nations have seen the alliance as serving their interests. The strength of the alliance lies in the depth of Australia’s military integration with the world’s most powerful nation and the immense dividends and financial benefits this has generated – but that remains viable now only with sufficient shared strategic purpose in meeting the China challenge. Just as there was nothing inevitable about the alliance’s formation, there is nothing inevitable about its future.

Australia has lived with its US military alliance for 70 years, the September 1 anniversary being next Wednesday – and that is more than half our life as a nation. Its endurance is a remarkable story of diplomacy, war, politics and reinvention.