Think things are bad now? The world is giving us a hefty pay cut

A nasty US-China trade war and a plunge in our export earnings will make it much harder to fund social services – and fix the budget.

The home front is grim at the moment. Companies and consumers are striving to find their mojo as governments pump in rocket fuel to ease the pain from high prices on families and keep Australia’s engine running.

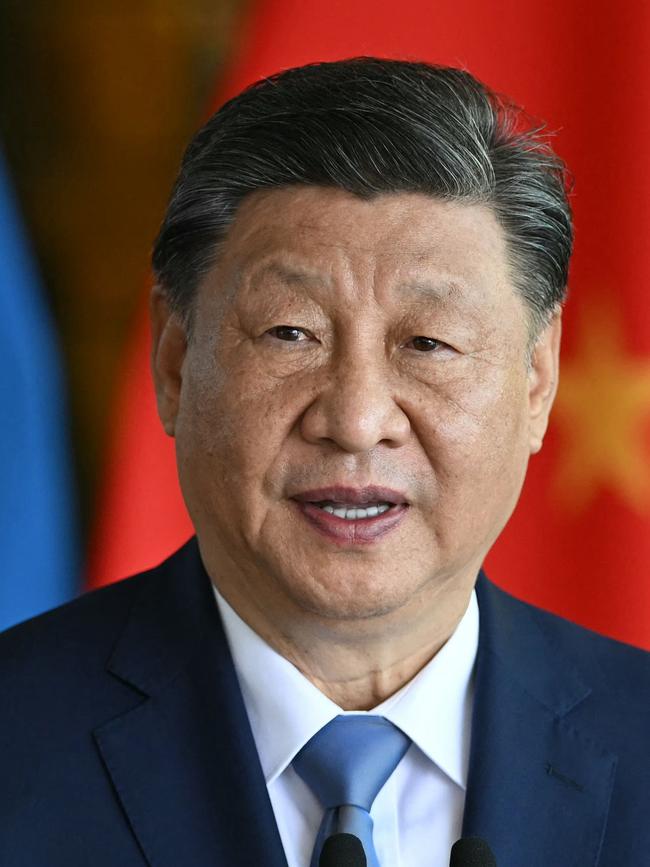

Outside of the Covid crisis, we’ve just lived through the weakest economic expansion since the early 1990s recession. Living standards have slipped back to where they were during the pandemic. There has been virtually no growth in our productivity since 2016, an indictment on the entire political class – red, blue, green, teal and the rest of the crazy colour wheel of the Canberra crossbenches. To add to the misery, the world has turned against us, not for us. China’s economy is a worry – for a billion Chinese people and 27 million Australians.

One-third of the value of our exports last year were to China. Its property sector is in trouble, officials keep messing up rescue efforts; among other things, that’s bad news for the price of iron ore, our top export. Australia has been hit with a colossal pay cut, putting immense strain on Canberra’s tax take. The purchasing power of our exports – known as the terms of trade – have plunged by more than 17 per cent since the middle of 2022, as the price of our key extractions come off historic highs.

And now Donald Trump is zooming in off a Florida fairway, blustering about tariffs, drugs and illegal migrants on Truth Social on his way to his second inauguration. This is not a new beef for 100 per cent prime America.

This week the Biden administration announced another round of export controls to stop sales of chip technology to China. Beijing duly responded by banning exports to the US of a range of obscure items on the periodic table that are vital to semiconductors and military applications.

It’s tit for tat between the globe’s heavyweights and that’s before Trump, who campaigned on a 60 per cent impost on imports from America’s geostrategic rival, takes the oath of office.

Asked about what’s coming down the line, Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock told an Australian Securities & Investments Commission forum last month: “We don’t know how other countries are going to respond to tariffs … Ultimately, if it’s not good for the Chinese economy, it isn’t good for us either.”

In its latest Economic Outlook, published on Wednesday, the OECD said the world economy was showing resilience in uncertain times but highlighted emerging risks, particularly from the stockpile of restrictions that now cover 12 per cent of all global merchandise trade. (In 2009 it was less than 1 per cent.)

“Rising trade tensions and further moves towards protectionism might disrupt supply chains, raise consumer prices, and negatively impact growth,” the OECD said. “Similarly, an escalation of geopolitical tensions and conflicts risks disrupting trade and energy markets, potentially fuelling rises in energy prices.”

In its focus on our country, the Paris-based body noted that with exports accounting for more than a quarter of GDP, Australia was exposed. “Australia is particularly vulnerable to weakness in China’s economy, although this is a two-sided risk as Chinese policy stimulus could boost Australian exports by more than expected.”

The world’s second largest producer has been performing below par, with sub-5 per cent growth expected this year and over the following two; before the pandemic, China was growing at an annual average of 7 per cent. Those missing two clicks matter a lot to its citizens and the rest of the world.

Like everyone else with vast exposures and a huge customer base, economists at the Commonwealth Bank have tried to estimate the likely damage to trade, economic growth, commodity prices, interest rates, the dollar and the federal budget from this dangerous dynamic.

Direct impacts from Trump’s tariffs are likely to be limited, but second-round effects from a slowdown in China will pack more of a punch through reduced demand for commodities and services.

China’s attempts at stimulus have been more miss than hit. Bullock told the ASIC forum: “It’s in our interests that China grows a bit quicker than it is at the moment … Whatever they can do to improve, particularly consumption, I think would be beneficial for us.” Plus China’s housing market was still a huge drag on Chinese activity, “and that’s a big thing that drives demand for our commodities”, the central bank chief said.

In a speech next Wednesday, RBA deputy governor Andrew Hauser will flesh out the risks and opportunities for Australia from these global developments.

When Labor came to power in the June quarter of 2022, Australia posted a trade surplus – that is exports minus imports – of $40bn. This week’s national accounts showed the bounty had shrunk to $3.3bn as prices fell for iron ore, lithium and coal, and disruptions hit LNG production. That has been the reason for a hefty fall in mining and resource company profits, and the portfolio pain for the multitude of passive owners of blue chips such as BHP, Rio Tinto, Fortescue and Woodside.

But trade in services has provided the killer blow. Tourism exports are around one-quarter below their 2019 levels. For Australians holidaying during Europe’s summer, including the Paris Olympics, that spending is a service import; the crackdown on foreign students, however, has cut our export earnings. The services trade deficit of almost $12bn was the highest recorded.

All this imperils the federal budget, which has taken on permanent spending during a temporary revenue bonanza. We’ve seen this movie before; it ends with a trail of wreckage, of budgets blown and cuts to the bone.

This week budget expert Chris Richardson reminded us of how lucky we’ve been, no one luckier than Jim Chalmers, whose tax take kept getting bigger as the post-Covid pie got bigger. War pushed up our commodity prices, migration increased the size of the economy, and inflation meant families got less of the pie and the tax man got more.

“Economic conditions just delivered the most favourable environment to the budget in a century and a half,” the Rich Insight principal writes in his mid-year budget preview, which analyses what has happened to the $365bn in revenue upgrades. In net terms, Labor spent $60bn or one-sixth of that (specifically, $104bn in new spending decisions, $44bn raised in new taxes).

“In effect this government has been repeating the same mistake made by the Howard-Costello government, locking in extra permanent decisions that weaken the ongoing budget bottom line at a time when revenues are booming,” he said.

But the carnival is over. The Treasurer is expecting a slightly smaller tax take. “The switch from write-ups to writedowns in our tax revenues is happening for several reasons,” Richardson said. “One is as simple as the fact that the world is now giving Australia a pay cut – a big turnaround from the earlier (and magnificent) phase of pay rises. That has removed the wind from beneath the wings of company tax.”

CBA economists Belinda Allen, Harry Ottley and Joseph Capurso argue Trump’s tariffs will be mitigated by our economy’s “shock‑absorbers” of a flexible exchange and interest rates, as well as a likely boost in government spending by Chinese authorities. “We consider a material downturn in Australia is unlikely but it is a headwind to take note of,” they wrote in a recent research note.

“If the trade policies are enacted broadly as announced, we would expect GDP growth in Australia to be modestly lower than otherwise, albeit the size is dependent on China’s growth and budget support. Slower Australian economic growth also implies the unemployment rate will be higher than otherwise.”

The impact on inflation will depend on the level of retaliation from other countries. “There is a probable scenario in which consumer prices in Australia are lower in the near term due to goods imports from China becoming cheaper as producers attempt to mitigate the tariff impact and lose the US as a potential export destination,” they wrote.

“Australian consumers benefit as a result. Longer term, higher trade‑barriers globally will put upward pressure on inflation and would see interest rates settle higher compared to otherwise. But such an outcome would need to involve something comparable to a global trade war, which we do not consider likely.”

In its latest forecasts, the RBA last month wound back GDP growth due to a weaker trade performance. In its report, the OECD downgraded Australia’s growth for this year and next, to 1.1 per cent and 1.9 per cent, respectively, with exports taking a hit.

The Paris-based think tank said while strong growth in federal and provincial outlays was helping to offset weak consumer spending, “a degree of budgetary consolidation will be needed in the coming years to ensure that future fiscal pressures can be addressed”. That’s not going to be easy, given spending pressures from ageing, disability services, defence and debt interest. “Policymakers should beware in seeking to curb immigration to ease pressures on housing costs, of worsening labour shortages, including in house-building,” it cautioned.

The pain from a global pay cut, entrenched high borrowing costs, woeful productivity, risks of capital flight and a looming trade war is bad enough. Yet, with an election on the horizon, Peter Dutton is peddling sound bites that, if they were implemented as policy, would blow the budget, scare off investment and slash the skilled migration we need. Trump 2.0 is not the only right-leaning populist flirting with self-harm.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout