The nation is getting more expensive to run, invest in and house, revealed by a bulging and indebted state, an overly regulated private sector, threats of capital flight and the punitive cost of homes.

Corporate Australia – which employs five in six workers, commits to investment over decades, competes globally and provides returns for retirement savings – can see the coming peril.

This is not about talking the country down, but waking it up.

Voters increasingly believe the living cost squeeze reflects a failure of the political class to pay attention to their core concerns and everyday hopes and needs.

You can draw a direct, hard line from government complacency about our forlorn productivity – basically, how much we produce with the toil and capital we put in – to today’s malaise in material living standards.

Yet we’re in a form of post-pandemic suspended animation on economic policy in Canberra.

The incumbents suffer an “optimism delusion” about the primal power of government to harness animal spirits; its opponents are tripling down on the force multiplier of grievance.

Migration and public spending, on benefits, public servants and capital works, have kept us out of recession, while contributing to a homegrown housing crisis.

We’re kidding ourselves to think housing will sort itself out if we just stop the visas, hobble demand and root out a few criminals on building sites. It’s a chronic condition.

The average cost to build a new home increased by $100,000 over the past four years; the time from commencement to completion of a new house has ballooned from about six months to nine months.

We have gradually become a high-cost producer, high-calorie consumer, running out of luck.

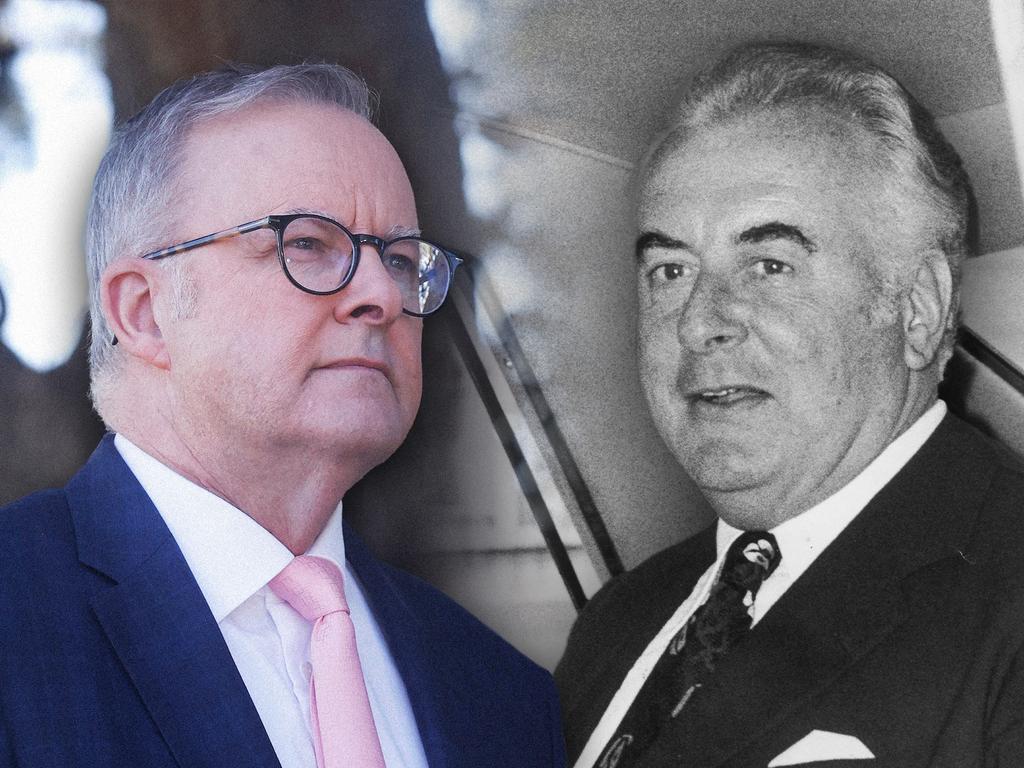

On the cusp of the reform era that began in the 1980s, politico-economic journalist non pareil Max Walsh described Australia as a “poor little rich country”.

Yet over two decades, leadership, vision, courage and community sacrifice fashioned a policy consensus that raised living standards by changing the way our economy operated.

There was disruption, especially for low-skilled and older workers, yet everyone stepped up: the place was more dynamic and we prospered.

The China booms simply added icing to a bigger cake, and cleared the debt, but we slowly drifted from our game plan of constant improvement to fighting over the spoils.

We’ve regressed.

There’s a big policy agenda for change: tax, energy, workplace laws, mergers, migration, red tape, zoning, education, infrastructure and government services.

It hasn’t changed much over recent years and we’ve managed these transitions before.

Some productivity fixes are staring us in the face, such as not restraining workers from switching to better jobs.

Wesfarmers chief Rob Scott says the mobility killer of stamp duty means people are stuck in homes that no longer suit them and workers are less able to chase opportunities that would benefit them, businesses and the nation.

Labor’s revival of national competition policy, where the states are duly compensated for a loss in revenue by Canberra for removing barriers to overall efficiency, is a promising move.

Instead of putting a mere $900m on the table to get things moving, the Feds should multiply that by 10, and ditch the Future Made in Australia folly.

Worse, in the post-pandemic period, government has got bigger, the economy has lost dynamism, workplaces are less flexible and there’s a worldwide retreat from free trade that is very bad news for us.

Even as the evidence of poor performance keeps mounting, voter fury is rising about how politicians go about their work.

New results from the True Issues survey by JWS Research, provided to The Australian, show a staggering two-thirds of voters agree with the statement “politicians treat politics as a game, not as something that directly affects people like me”.

No wonder the major parties are losing market share.

As we move close to a federal election, JWS’s Tom Cameron says voters will be grilling the political class: “Are you paying attention?”

There will be blood.

Many of today’s leading figures have studied the reform era, which was imbued with big personalities and grand policy moves.

But Labor and the Coalition have come away no wiser; where there’s passion, there’s no purpose; where there are ways, there’s no will.

Getting out of this rut will take small steps and constant motion.

Yet faced with this blindingly obvious task, both sides are guilty: dumbstruck and obsessed with the wrong game.

Australia is in a rut: becoming older, flabbier and less nimble to play to the conditions.