Labor ignores lessons of history at its peril

A cultural and economic clash may be unfolding on a scale not seen since Gough Whitlam’s term. The prediction? Labor will end up on the wrong side of it.

Australians are living under the weight of the sharpest decline in living standards since World War II. This is a reality that Labor’s economic narrative strives to ignore. It is a perilous omission.

Instead, in only his second ministerial statement to the parliament on Wednesday, Jim Chalmers talked up his achievements in bringing down inflation. The federal Treasurer suggests it is all going to plan and the nation is heading for the fabled soft landing hoped for in the economy.

Yet Chalmers continues to challenge the central bank’s stated concerns on inflation while claiming had it not been for Labor spending, the economy would have been in recession.

The inherent risk in this approach is obvious. The experience of many households jars with this account. And the disengagement with voters who believe Canberra has abandoned them will only accelerate between now and the next election without interest rate relief in sight.

But there is a deeper thread running through the fabric of a political contest that may challenge Labor in a potentially profound way. A conviction is emerging in conservative circles that a clash of economics and culture is about to unfold, and that Labor will end up on the wrong side of it.

Rather than readjusting its thinking, the Albanese government is leveraging incumbency to deliver on an established ideological agenda that ignores the cultural risk. A conspicuous example of this came on Thursday when Chalmers announced he would amend the Future Fund’s mandate to direct investment into sectors aligned with Labor’s political agenda. Just as Mark Latham had once proposed the civilising of global capital, Anthony Albanese seeks to harness this capital to serve Labor’s political and ideological objectives.

While the Coalition has questioned the legality of what it alleges is a political raid on the Future Fund, Chalmers’ continuing institutional restructuring has further exposed Labor’s operating principles. It clearly now sees the Future Fund as a pacesetter for industry super funds. And presumably, by controlling capital, Chalmers believes Labor can control culture.

Harvard University professor Sam Huntington’s provocative 1993 prediction that a great reckoning would unwind Western democracies was illustrated through an envisaged clash of civilisations, based on heightened conflict between culture and religions. Huntington dismissed the role of economics in the reshaping of this new world order, assuming that culture was foundational. This assumption is now under challenge.

American professor of sociology Musa al-Gharbi, an African American Muslim, once cancelled by conservatives only to be embraced recently, charted the history of “woke” movements – or symbolic capitalism – in his recent book We Have Never Been Woke. It is a theme that has struck a nerve with the centre-right.

There have been four waves in the past century, al-Gharbi claims. All are directly linked to the fundamental changes in underlying economic conditions that have been significant enough to trigger social rearrangement.

Taken more broadly, an economic oversupply of elites – identified by their inherent social contradictions – helped fuel these movements, while economic downturns that affected both elites and non-elites alike smothered their intensity due to the inability of societies to absorb them and their demands.

The first was in the 1920s, when the social justice movement began to collapse under the weight of the Depression. As George Orwell wrote at the time, it was an activism born of a professional class seeking self-enhancement through an alignment with the struggles of the marginalised.

The second wave came in the late ’60s and early ’70s, when a clash between economic decline and activism triggered another political tremor of significant force. Labor rode this wave into office with Gough Whitlam, on the back of the anti-Vietnam war movement, while assuming the good economic times would keep rolling on, until they didn’t.

Labor’s defeat after only three years coincided with a new cultural and economic reckoning. Al-Gharbi describes these periods as “Awokenings”.

There was a third wave in the late ’80s and the dotcom boom, also snuffed out by recession, with the fourth phase beginning in the post-global financial crisis environment and the Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011.

It is this fourth wave, which expanded into corporate virtue signalling, that al-Gharbi argues is now in decline, aligned to the dramatic readjustment of Western economies. The election of Donald Trump provides a proof point to this theory. And the effect has been to spectacularly reshape political authenticity.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor is convinced of this argument and the unmistakeable parallels with the ’70s. On a measure of living standards, the Coalition’s argument is that the current cost-of-living crisis is in fact worse than under Whitlam. And there will be a consequential downstream cultural effect to this.

Caution should be applied to drawing parallels to Whitlam. But the Albanese government itself invites the comparison, having presided over an unprecedented decline in living standards since coming to office. Real disposable incomes have fallen almost 9 per cent in just two years, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the sharpest decline in living standards since the ’50s.

Unemployment was a greater problem under Whitlam. A 5 per cent rate of unemployment was considered high in 1975, when labour markers were less flexible. And inflation, at its peak, also hit 17 per cent by 1975.

Whitlam responded by delivering expansionary budgets with increased spending on Labor’s social agenda and public sector wages, often ignoring Treasury’s advice on the need for tax reform.

The experience for people, however, was different.

While there was enormous price inflation in the 1973-75 period, there was also huge wage inflation. The difference today is that the shock of the current cost-of-living crisis is being felt through this unprecedented fall in real disposable income. Wages haven’t kept up with prices.

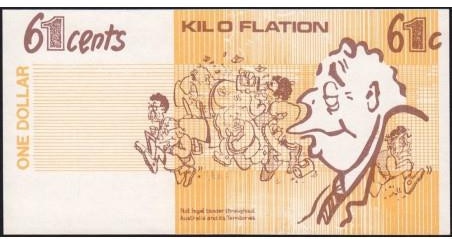

Taylor makes the point using a mock $1 note he handed out to voters at a rural polling booth in Nimmitabel in the NSW bellwether seat of Eden-Monaro in December 1975. He was only nine years old, accompanying his father, a strong Country Party supporter. Taylor insists that even at that age he understood what it meant.

On the front of the note, the $1 has been struck out and reduced to 61c, representing the depreciation of the new currency under the Whitlam government.

Across the top of the forgery is written KIL O FLATION, a play on Australia’s recent conversion to the metric system and the cost-of-living crisis households were facing.

The point was that in the short time Whitlam had been in office, the purchasing power of a single dollar had been reduced by 39c. Overleaf was a simple slogan that read: “It’s your money that keeps the Whitlam government spending madly and badly. Can you afford it?”

While not all his colleagues may agree, Taylor is convinced of the historical equivalence.

He insists that the next election can be fought from similar footings to those of 50 years ago that brought about the collapse of the Whitlam government after only three years in office. The dismissal may have been the cataclysmic political event, but Taylor says people forget, or are too young to know at all, that the issue that led to it was uncontrolled inflation for which Whitlam was ultimately blamed.

Taylor has been gradually but deliberately leading colleagues to this point, borrowing heavily from the Liberal Party’s pitch five decades ago against Whitlam’s mismanagement of the economy.

Peter Dutton was an early passenger, having picked the mood over the voice referendum, despite being told by many that he was wrong. It’s no surprise that the theme of the Liberal Party’s campaign will be built around the inflation problem and Labor’s contribution to it through extravagance. This has crystallised in recent months.

The Opposition Leader has begun to frame a narrower contest, moving to manage expectations around Coalition tax cuts that until recently were being planned as the centrepiece of its election agenda.

“These two issues leave all others in the dark,” says Taylor.

Economist Chris Richardson cautions against drawing too many comparisons with the ’70s but doesn’t deny the living standards predicament: “There is no argument that the fall (since 2022) is bigger than anything we have seen since 1959,” he says.

He says a more relevant comparison with the ’70s is the productivity problem. “The main parallel is a society coasting on its laurels for too long and not challenging itself with reform,” he says. “You have productivity that’s as sick as a dog.”

The similarity is the absolute weakness of productivity compared with earlier phases, including the ’70s. “And the productivity growth slowdown was because politicians didn’t do the heavy lifting,” Richardson says. “In the ’70s they didn’t do enough on tariffs, they were far too inward-looking, our businesses were way too protected, our public service had no imagination and wasn’t being listened to.

“Today our productivity is worse.

“It is a similar slowdown story but it has slowed down from a weaker starting point.”

This is an indictment not just of the current Labor government but of the Coalition government that preceded it.

“The living standards story shows we have had a lost decade. We have spun our wheels as a nation, and you could almost time it to the Hockey budget of 2014 when all our politicians retreated and decided not to be courageous,” says Richardson.

While this is at the heart of Albanese’s economic problem, the burning question, as al-Gharbi’s theory suggests, is what the secondary effect will be on culture. The Whitlam government’s dramatic rise and fall reflects the effects of the second wave of the al-Gharbi doctrine, Taylor believes.

This is not a controversial idea. And it shouldn’t be new to the Prime Minister, who was a student at the University of Sydney after the split in the economics department in the late ’70s, when the school of political economy was established.

As one fellow student recalls, even the Marxists conceded that economic material needs came before culture and ideation needs.

Both Albanese and Dutton are now participants in this contemporary struggle. The question is whether Australia has reached “peak woke” and what implications this will have on a federal election less than six months away.

Taylor is convinced by the argument and believes this clash will heavily influence the outcome of the next election. While some in the partyroom argue it is solely about the economy, Taylor argues that they can’t ignore the cultural element.

This belief is now shaping the Coalition’s policy agenda and Dutton’s own political adjustment. There is scope for Dutton to broaden appeal at a cultural level.

Conservatives see secondary education as a space vacant of debate but begging for attention.

While it may be a simplistic revision to suit a modern narrative – there are significant and obvious differences between 1975 and 2025 – there are undeniable parallels at both economic and culturally significant points in time.

In 1975, Australia’s population was half what it is now, personal computers didn’t exist and the internet and mobile phones were Jetsons-like thought bubbles. They were simpler times.

Ironically, the lack of global connectivity was a disadvantage to Whitlam, as the cost-of-living crisis domestically could not be imagined in a global context in the electorate’s mind, as it is today.

The average age of Australians was 10 years younger, people married younger, with different expectations, homes were more affordable and VCRs had only started to populate lounge rooms.

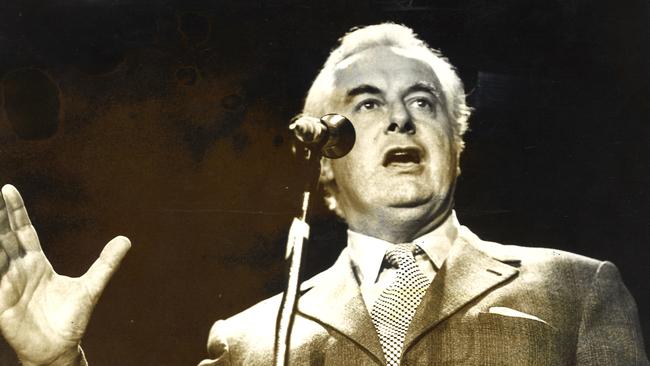

John Howard says the political differences at a leadership level were also markedly different, witnessing Whitlam in full stride after entering parliament in 1974.

“Whitlam had style, intellect and class,” the former Liberal prime minister says by way of an unflattering comparison to Albanese. “Whitlam also had a grand plan.”

Whitlam fashioned himself as the political zeitgeist of the social changes during that period. He was also the beneficiary of three decades of economic growth delivered through the post-war boom.

The Keynesians believed they had defeated the boom-bust cycle, as Whitlam’s Bankstown speech suggested, dismissing the fiscal cost of his grand plan as something that would simply be funded through the revenues delivered via the progressive tax system.

“The program” consisted of ending Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam war, free education, universal healthcare, equal pay, land rights and environmental protection. The most significant social change, according to Howard, was the Family Law amendments introducing no-fault divorce.

Australians today live in a world much changed by Whitlam. Some would say much for the better.

But for Whitlam the deteriorating economic conditions during 1974 became an irritant that stood in his way of achieving Labor’s social transformation, rather than a problem that had to be dealt with in and of itself.

Howard wrote in his autobiography, Lazarus Rising, that some in Whitlam’s cabinet could see the problem as inflation soared and unemployment began to rise.

“By contrast, Gough Whitlam not only failed or was unwilling to acknowledge the new realities, but appeared hurt by them, as if such diversions had no right to interfere with his grand plan for Australia,” Howard wrote.

One of the Coalition’s claims against Albanese is that he has been similarly afflicted by an annoyance that the inflation crisis that has evolved during his first term has obstructed his social agenda.

The focus on the voice referendum for much of last year, at the height of the inflation problem, led to claims that Albanese also lacked an instinct for economics.

Albanese would contend that his election was similarly an endorsement of a progressive policy agenda. The momentum for this is now arguably in decline.

If true, the consequences could be profound for the reshaping of contemporary divisions and the tolerance of non-elites for Labor’s policy settings. Its climate change agenda stands out.

This is where the return of Trump has a deeper meaning for the Albanese Labor mission. Trump as president may or may not end up being a danger to Albanese’s agenda, but the circumstances that gave rise to his resurrection should be of some concern.

If al-Gharbi is right in his analysis, the West is again at a cultural pivot point, similar to the mid-’70s and other periods when the interests of the elites and non-elites collapsed together as economic conditions conspired to inflict hardships on all.

How much of the experience of the Whitlam era can be applied to the modern settings is debatable. But for Taylor the fundamental conditions apply.

And they are that Labor has failed to acknowledge economic realities and, as a result, the delivery of its social agenda risks being rejected.

All this has been occurring within just three years – the same time it took to witness the rise and fall of Whitlam.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout