The scales symbolise a system where the starting point, the presumption of innocence, addresses the obvious power imbalance between, on the one hand, a citizen facing imprisonment and, on the other, the tremendous power and resources of the state.

The sword signifies the necessary power of the justice system to punish perpetrators who commit wrongs.

The blindfold means the fundamental principles of the legal system apply to every person, equally. Perhaps the most important of the fundamental principles is the presumption of innocence. It’s the golden thread that weaves together a just society, protecting us from the tyranny of mob injustice.

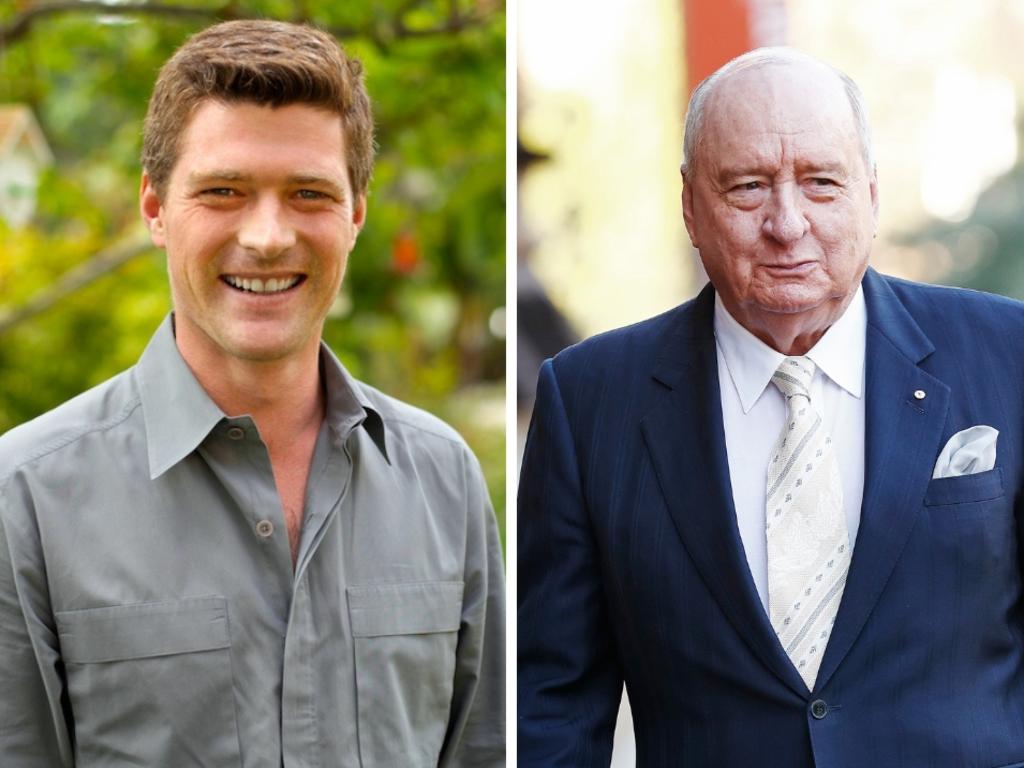

This week, the whiff of sanctioned mob justice was unmistakeable. Some of those best placed to uphold the presumption of innocence are the same ones who ignored it, after Alan Jones was arrested and charged with more than two dozen alleged offences against nine men over two decades. His youngest alleged victim was 17.

The presumption of innocence was undermined when NSW Assistant Police Commissioner Michael Fitzgerald fronted the media and described the complainants as victims. He commended the “victims” for their “bravery in coming forward”.

“The victims have our full support. This is what they have been asking for,” he said. “These are serious charges.”

Equally serious is the presumption of innocence. There is no “victim”. Not yet. There is a complainant.

Praising a “victim” may suggest to potential jurors that police want the public to know that law enforcement officers believe a crime has been committed and that the defendant is guilty.

But there is not yet a crime. In the absence of a guilty plea, a jury will be the arbiter of fact. That jury can find guilt only if it believes it has been proved beyond reasonable doubt after consideration of the admissible evidence. And the jury’s starting point is the presumption of innocence.

It’s one thing for Australia’s richest person, Gina Rinehart, to remove nice things that Jones said about her from her personal and corporate websites. Private citizens are entitled to believe what they want. But a police officer of any rank should know that calling a person who has made an allegation a “victim” undermines the presumption of innocence.

If police and others across the criminal justice system don’t defend the presumption of innocence in their dealings with the public, the immediate danger is that jurors won’t understand that Lady Justice’s blindfold means that the presumption of innocence applies with equal force to our best friends and our worst enemies.

Once we lose that, then the jury system – described this week by senior Sydney silk Arthur Moses as the essential guardrail in a democracy – isn’t worth a jot.

I would launch this strident defence of the presumption of innocence even if Jones were my foe. That Jones is a friend of mine is neither here nor there.

A good portion of the media take the presumption of innocence seriously. But when, in the first press conference after Jones’s arrest, a senior policeman calls a complainant a “victim”, the media will report that.

When police tip off the media about the arrest of a man with as high a profile as Jones, the media will film that.

Still, there are plenty in the media also laying down impressions that here’s a man who has rightly met his comeuppance.

Why can’t Jones’s enemies see the longer game? What if the tables are turned on those celebrating Jones’s downfall – or on one of their friends? What then will they say about the presumption of innocence? Let us be grateful for small mercies. As one reader wrote this week, “Thank god we don’t have firing squads and hanging any more. Cemeteries would be full.”

It’s not just senior police officers who appear to be casting aside fundamental tenets of our criminal justice system. When ACT Chief Justice Lucy McCallum said last week that she struggled to understand why juries found it so hard to believe an allegation of sexual assault, she left many people baffled and disappointed.

Many were concerned that her words would be interpreted as telling prospective jurors that they ought to find it easier to believe sexual assault allegations.

All judges, let alone a chief justice, should be very careful that everything they say and do serves the administration of justice.

Senior criminal barrister Jack Pappas put it this way: “Judges are appointed and paid to hold the reins of fairness and to steer the lumbering wagon of justice down the middle of the road, not to the right nor to the left but down the middle to ensure that complainants and accused persons and the community receive a fair go.

“When judges start to deviate from that straight path and cannot help doing so, they should get off the wagon and give the reins over to another who is not so affected,” he told Inquirer this week.

Pappas is concerned that when a chief justice expresses disbelief about why juries find it, in her view, unjustifiably hard to believe allegations of sexual assault, it “sends a dangerously destabilising message, not only to potential jurors but to other judges under her direction as head of jurisdiction and a dangerously disquieting message to any accused in a sex matter being overseen by her”.

These days, bar associations and other legal professional bodies rarely say boo about fundamental principles. But Brodie Buckland from the ACT Bar Association delivered a rare rebuke.

He said McCallum’s comments might give rise to perceptions that “juries in sexual assault trials are getting it wrong because they do not believe the allegations made by complainants”.

“Such perceptions do not serve the interest of justice and ought to be rejected,” Buckland said. He defended juries as the ultimate arbiters of fact.

“They are foundational to the common-law criminal justice system and their decisions must not be gainsaid,” he said.

Pappas is concerned that McCallum’s public comments may intimidate young and relatively inexperienced defence barristers, dissuading them from testing allegations in court against their clients.

“Other more experienced and resolute barristers may push back, but a criminal trial should not be a contest between the judge and those at the bar table to achieve fairness. The judge should guarantee that fairness,” he said.

Some senior lawyers in the ACT are asking privately whether McCallum is slipping into law “reformer” mode, angling for a return to judge-only trials for sex offences. When the ACT allowed for judge-only trials for sex matters, conviction rates were low. But no one imagines that would remain the case with a Supreme Bench headed by McCallum and composed of different judges from those in previous years.

A former criminal prosecutor said that returning to judge-only trials for sex offences would raise even deeper concerns for the presumption of innocence in the ACT, given McCallum’s comments about juries finding it so hard to believe allegations of sexual assault.

McCallum is not alone in her apparent drive to raise conviction rates for sex cases. In the ACT, the use of the term victim survivor instead of complainant is endemic, delivering added injury to the presumption of innocence with its emotional tagline of survivor.

Historically, the term complainant was used up until an accused person was convicted at trial or pleaded guilty. But as another very senior ACT lawyer told Inquirer: “The government now uses the term victim survivor to describe anyone who complains of being the victim of sexual assault or domestic violence. It features heavily in most government documents, reports, press releases which relate to alleged sexual offending.”

In circumstances when there has been no conviction or guilty plea, the lawyer says, victim survivor is a “highly charged and loaded term … that completely undermines the presumption of innocence and is grossly inappropriate”.

The lawyer says while some former and current prosecutors refuse to use the term because they understand how unfair and inappropriate it is, government departments and other agencies in the criminal justice system routinely use the loaded term.

It’s disturbing how many people chip away at the presumption of innocence, disregarding that old proverb: there but for the grace of God go I – or go the people I love.

When McCallum aired her misguided views, she opened a can of worms about the flawed administration of justice in the ACT.

We’ve only just started exposing the mess where people entrusted with tremendous state power, across different legal institutions, are determined to press down on one end of Lady Justice’s scales to lift sexual assault conviction rates, at the expense of a fair trial for an accused.

Not for nothing, Lady Justice holds a set of scales in one hand, a sword in the other and wears a blindfold. If we remove even one of these items from our justice system, we’re all in strife.