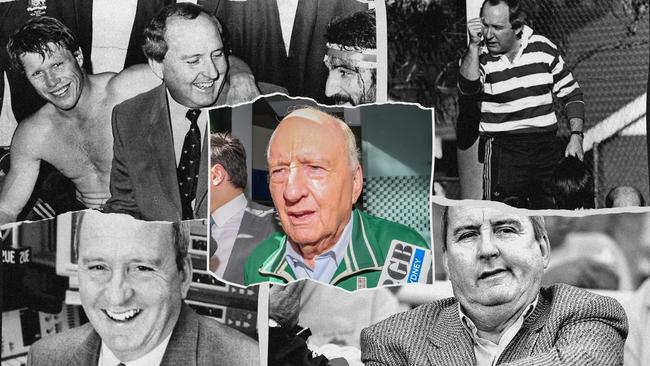

Alan Jones looks to his ‘pick and stick’ club as he faces the fight of his life

The legendary broadcaster will be counting on his coterie of celebrity and political supporters as he faces multiple charges of indecent assault and inappropriate touching.

As Alan Jones begins the toughest fight of his life he’ll be looking to see who among the celebrated members of his “pick and stick” club remain loyal as he faces charges of indecent assault and inappropriate touching.

For years, the legendary broadcaster has counted on the likes of billionaire James Packer, television host Karl Stefanovic, celebrity accountant Anthony Bell and a raft of other movers-and-shakers to stand by him when controversy hits.

On Monday night, Sky News commentator Peta Credlin, a long-time Jones supporter, was one of the few to offer a public comment.

Criticising the police for clearly tipping off the media about Jones’ arrest, Credlin said: “I wish my friend well for what will be a difficult few months ahead.”

However, it seems possible that Jones’ support crew may have inadvertently contributed to his current predicament, with claims that one of his accusers, identified by the pseudonym “Bradley Webster”, only filed a police report after becoming incensed after being publicly slammed for making allegations under the cloak of anonymity.

The 83-year-old Jones, known to his detractors as “The Parrot”, has survived decades of merciless speculation about his private life, inquiries into cash-for-comment deals, huge defamation payouts and damaging advertiser boycotts.

But there’s never been anything quite like this.

The right-wing radio host has been one of the dominant figures in Sydney’s public life for more than 40 years, most recently from his perch above the harbour in “the Toaster”, a building almost as controversial as its most famous resident, where deals were done that reshaped the city and where, on Monday morning, an unwelcome knock from NSW police shattered his semi-retirement.

It’s difficult to overstate Jones’s power in the 1980s and ’90s, and through the early part of 2000s.

The immediacy of radio, now eroded by the reach of social media and the fragmentation of mainstream media, put the take-no-prisoners broadcaster at the intersection of Sydney’s favourite intrigues: politics, business, sport and crime.

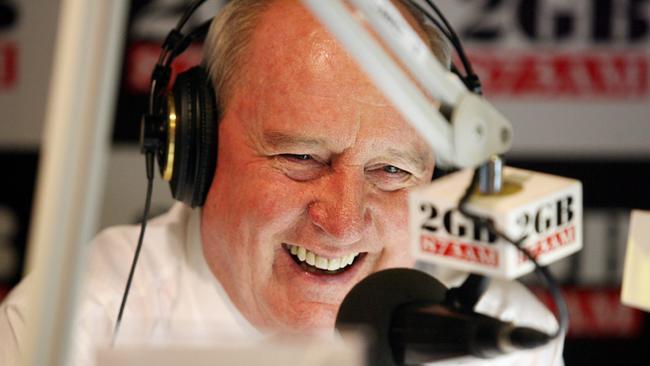

Jones was a disrupter; an anomaly in breakfast radio, known for his aggressive and confrontational style.

In the days Before Alan, breakfast radio was a light and cheerful place. What’s happening around town today. Weather and traffic. The heavy stuff came at 9am.

Jones threw out the playbook. He was happy to thump the table and harangue politicians, with seven or eight-minute lectures from the pulpit, three times a day.

It wasn’t supposed to work at that hour, but it did.

Jones had conviction and relentless energy – which didn’t end when he walked away from the microphone at the end of a shift.

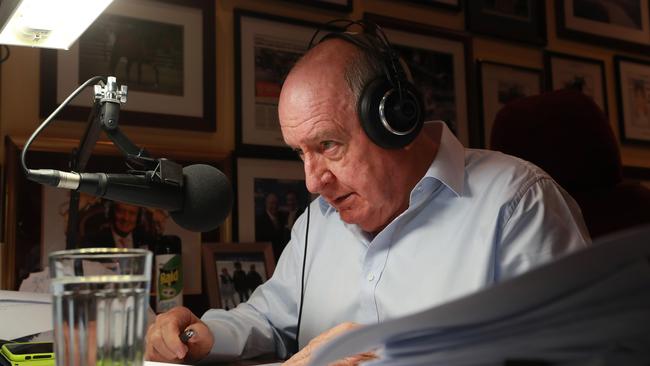

He’d go home to write letters, thousands every year, bombarding politicians, bureaucrats, business leaders – anyone with a finger in Sydney’s pie.

State and federal leaders of all political persuasions sought his counsel – or received his forthright advice even if not asked.

Leveraging his radio show and his conservative audience – not just tradies and taxi drivers, as his detractors would often sneer – Jones became arguably the most powerful political figure in the country outside Parliament.

Both on air and off, he was a bully, relentlessly pursuing results for himself, his “picks” or his listeners through phone calls and relentless letter writing.

His letters to politicians frequently mixed flattery and threats in the space of a single sentence.

His broadcasts often involved lengthy monologues and lectures, followed by interviews that were highly controlled and question-heavy, with responses limited to “yes, Alan” or “no, Alan”.

Even the ABC shrank in the face of Jones’ power when push came to shove.

In 2006, when journalist Chris Masters wrote Jonestown, a biography of the radio star which dealt with his homosexuality, Jones threatened to sue.

The ABC, which had been due to publish the book, cancelled the contract on the grounds that it would “almost certainly result in commercial loss, which would be irresponsible”.

When Allen & Unwin picked up the book it became an instant bestseller.

It’s hard to imagine a Sydney that had never had Alan Jones.

Would the city have Barangaroo in its current shape if Jones hadn’t lobbied on James Packer’s behalf for a second casino, at a private lunch with then NSW premier Barry O’Farrell, held – naturally – in Jones’ apartment?

Over a meal served on Jones’ grand timber dining table, “Mr Packer outlined his vision to build a $1bn-plus hotel, casino and entertainment complex at Barangaroo”, the scathing Bergin report into the deal found.

“Later in February 2012 concept plans for a state-of-the-art, 350-room hotel and casino at Barangaroo were released to the media,” the report noted.

The following year, the government changed legislation to allow for a second casino to operate at Barangaroo.

Jones didn’t always get his way. When in 2014 he demanded Malcolm Turnbull – then trawling for the Liberal leadership – pledge support for Tony Abbott’s strategy, Turnbull told him curtly: “Alan, I am not going to take dictation from you.”

Not that Jones was going to let Turnbull have the last word.

“You have no hope ever of being the leader, you’ve got to get that into your head,” Jones told Turnbull, who became prime minister the following year.

Jones’ pick-and-stick mantra was on display in many of his causes – including support more than a decade ago for Kathleen Follbigg, convicted of killing her four children but since pardoned.

But it was also on display even in the face of overwhelming evidence that he’d backed the wrong camp.

He campaigned for convicted murderer Andrew Kalajzich, demanding a new investigation into the case – which was duly established, only to provide further evidence of Kalajzich’s guilt.

He weighed in behind the false claim that Queensland’s Wagner family were responsible for the deaths of 12 people in the 2011 floods in Grantham, Queensland – a pick that cost him and his employers a $3.7m defamation payout.

But it was Jones’ treatment of women that spelt the end of his career.

In 2018 he had a fierce on-air confrontation with Sydney Opera House chief executive Louise Herron over her opposition to a plan to project The Everest barrier draw on the Opera House sails.

“Who the hell do you think you are?” Jones thundered, refusing to listen to Herron’s answers during the course of a brutal attack, and calling for her to be sacked.

Jones ultimately apologised, but not before the Berejiklian government ordered the Opera House to project the draw on the sails, complete with jockeys colours and barrier numbers – in contravention of a policy to prevent the commercialisation of the building.

But a forced apology was never going to mark the emergence of a reformed Alan Jones.

The star had surrounded himself with yes-men. No one, it seemed, was protecting him from himself.

The times were changing but Jones was not for turning.

Anyone else might have taken the cries of misogyny and changed course. Jones doubled down.

When New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern had a crack at Australia’s climate policies in August 2019, Jones suggested then-prime minister Scott Morrison should “shove a sock” down her throat and get tough with a “few backhanders”.

The comments had a negligible effect on ratings – Jones’s rusted-on audience lapped it up.

But many of Nine’s biggest advertisers didn’t.

Already a target for online activist groups like Mad F..king Witches and Sleeping Giants, companies like Coles, Ikea, Renault Australia, IGA and Chemist Warehouse told Nine they were pulling their ads – not just from Jones’ show, from the network.

Jones responded by urging listeners to give Coles “a wide berth”.

“We can both play the same game,” he said. “And good luck to you by the time I am finished.”

But the writing was already on the wall.

Nine hit the dump button and Jones was out.

Both the radio network and Jones claimed “health reasons”.

The reality was, Jones’ position had become untenable.

His farewell party, at a lunchtime cruise aboard Anthony Bell’s $15m superyacht on Sydney Harbour, was packed with the rich and powerful: Tony Abbott and Peta Credlin, retired Test cricketers Brett Lee and Shane Watson, footballers Kurtley Beale and Craig Wing among them.

Others who have been seen as part of Team Jones in previous years, including former prime ministers John Howard and Tony Abbott, declined to comment.

As he faces a likely criminal trial next year, he will need all the support the pick-and-stick club can give.