Alan Jones was untouchable — until suddenly he wasn’t

As his lawyer pointed out after his arrest, Alan Jones is presumed innocent until proven guilty. But it is legitimate to ask why it has taken so long for the rumours, scuttlebutt and whispers that have surrounded him for the past four decades to coalesce into police charges.

There is an old saying in the media business, attributed to Shakespeare, that truth will out. In a year or so, we should know whether this adage applies to Alan Belford Jones.

Because it is likely that a jury will decide the truth or otherwise of the charges of sexual offending levelled against Jones this week.

As his lawyer Chris Murphy pointed out after his arrest, Jones is presumed innocent until proven guilty. So there will be no comment here on the matters now before the courts.

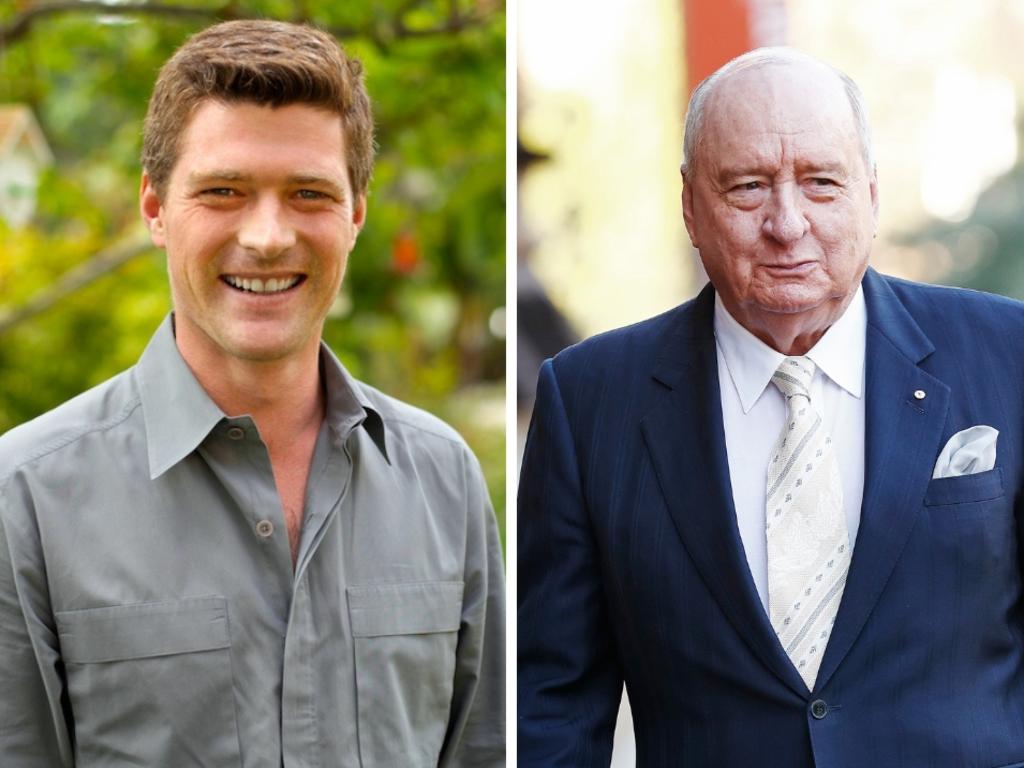

But it is legitimate to ask why it has taken so long for the rumours, scuttlebutt and whispers that have surrounded Jones for the past four decades to coalesce into police charges – 26 of them involving nine men, including an unnamed Olympic star and a 17-year-old youth. Forty years. Who knew?

Well, in a way, we all did. But what was done about it?

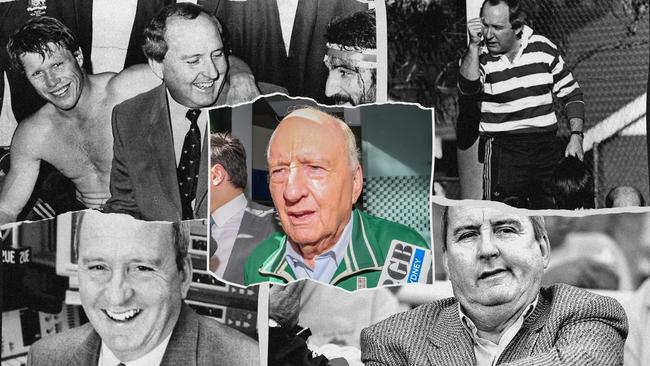

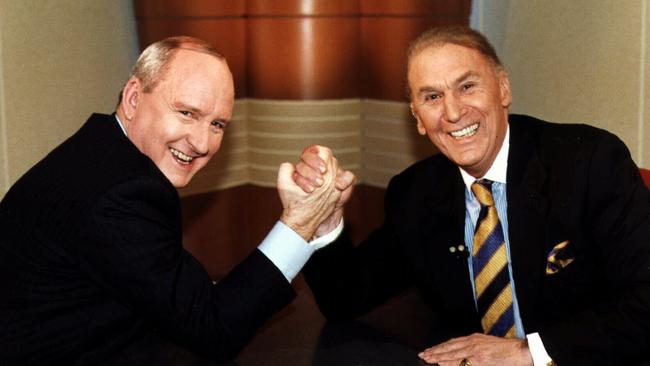

I was part of the 2UE talk team in 1987. Alan and I were described as “shits that pass at the mike” because he was on the breakfast shift from 5.30am to 9am, while I enjoyed far more gentlemanly hours on drive, from 4pm to 7pm.

Our paths rarely crossed. When they did we were courteous and respectful towards each other. I observed his extraordinary ability to mesmerise audiences with hot-gospelling florid word salads about the soaring achievements of people or sporting figures that he described as adornments to the nation, the community or themselves.

I also heard all the office goss. Back then, when Alan was in his first years as a radio star, most of the whispers were about whether or not he was gay. Others were about his volcanic temper and his propensity to rip fellow workers to shreds over perceived failures.

The whispered questions over sexuality were answered in the minds of all but a few blue rinsers after the London toilet affair. Jones was charged with offending public decency in a Soho toilet but the charges were eventually discontinued amid rumours that former prime minister Malcolm Fraser (for whom Jones had been a speechwriter) had interceded with British prime minister Margaret Thatcher to have the charges dropped. Others attributed Jones’s good fortune to the lobbying efforts of former MP and celebrity author Jeffrey Archer.

Jones returned to the airwaves untouched by the scandal. The prevailing attitude was: “So, he’s gay? So what?” His ratings soared and his power grew. Only Jones will know if this great escape emboldened his private dealings, but his power certainly enhanced his capacity to box the ears of politicians, public servants and anyone, for that matter, if they dared to propose policies that Jones deemed unsuitable.

Bob Carr, a former NSW premier, once told me he chose to bow to Jones’s demands because if he didn’t, he would face weeks and months of on-air haranguing and verbal assaults. Rather than being distracted and abused, he reasoned it was far better to agree with Alan, take the kudos that came with that, and get on with running the state.

Jones again demonstrated his amazing capacity to emerge from controversy unscathed after the 1999 cash for comment affair. Initially, the scandal involving the secret payment of huge sums of money for unscripted on-air comments, was centred on 2UE morning star John Laws. But it soon emerged that Jones was an even greater recipient of funds, which he asserted would not have influenced him in any commentary he chose to make. It was an argument based on improbable logic and he and Laws were both found guilty of breaching broadcasting regulations.

It was Jones’s claim during his evidence that his job was to “tell people what to think” that led me to a decision not to tune in to Jones any more. I preferred to make up my own mind, thank you.

But there was no impact on his wider cult-like following. Ratings held up and Jones ploughed on, clocking up more than 200 wins in Sydney audience measurements.

Much of Jones’s influence was positive. He helped raise millions for charities and other worthwhile causes, but more headlines were generated for other reasons. In 2005 Jones was again castigated by broadcasting authorities for inciting hatred, contempt and ridicule of Lebanese Muslims in the lead-up to the Cronulla riots.

Not even the 2006 publication of Chris Masters’ meticulously researched book, Jonestown, could knock Alan off his perch. His lawyers sent the proposed publisher, ABC Books, a blistering warning that he would sue over any perceived defamation, causing the gun-shy broadcaster to pass on the project. It was picked up by Allen & Unwin and went on to be a bestseller. Jones did not sue. And it did not dent his power or ratings.

But times were changing. In the latter decades of the 20th century there was a kind of wilful community blindness to what is now considered sexual misconduct with minors. That began to change after BBC star Jimmy Savile was unmasked as a serial sexual predator in 2012.

Then Australian entertainment star Rolf Harris was confronted with molestation charges in 2013. Both were precursors to the seminal change wrought by the MeToo movement, which grew out of the 2017 charges levelled against jailed Hollywood mogul, Harvey Weinstein.

By 2020, amid community dismay and revulsion at revelations about sexual misconduct, including among priests, forces that would be lethal to Jones’s career began to emerge.

The business equation with radio ratings was simple: more listeners equals more revenue equals more profit. Jones was a profit powerhouse for John Singleton’s 2GB and was untouchable. Until he wasn’t.

Jones’s bitter condemnation of prime minister Julia Gillard as Ju-liar, who “should be put in a chaff bag and taken out to sea”, and New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern, who “should have a sock shoved down her throat”, mobilised women’s groups. One, known as Mad F..king Witches, campaigned for a boycott of Jones’s program.

Major sponsors deserted. Suddenly, the equation shifted: ratings high but revenue low. The cash cow was now a financial liability. And doubly so when he lost a defamation case against Toowoomba’s Wagner brothers which cost 2GB $3.7m, plus costs.

Jones resigned from 2GB in May 2020, citing health concerns. About the same time, Sydney Morning Herald investigative journalist Kate McClymont began accumulating statements from a series of men who accused Jones of unwanted sexual attention.

Mainstream newspapers don’t rush into print when they hear rumours, particularly those concerning powerful people with the willingness and capacity to litigate. Editors insist that allegations be thoroughly checked out, and if the allegations involve criminality, checked again. Corroborating evidence is required, sworn statements taken and submitted to exhaustive legal assessments. Is the story defamatory? If so, is it defensible? On what grounds?

It took almost four years before SMH lawyers gave the green light to publish a year ago. By any definition, it was brave reporting and brave publication.

Jones immediately announced he would sue. He has not. Despite saying he would again be proselytising his opinions on radio-like streaming channels, he has not done so.

Since March this year he has been under investigation by a specialised force of detectives in what NSW Police Commissioner Karen Webb called “a very long, thorough, protracted investigation”.

Jones has denied the charges. He will next appear in court on December 18. If the matter progresses to court, it may be 2026 before a verdict is handed down.

As Shakespeare observed, sometimes it takes a long time for the truth to be revealed.