The room where it happened: Gough Whitlam’s man in China

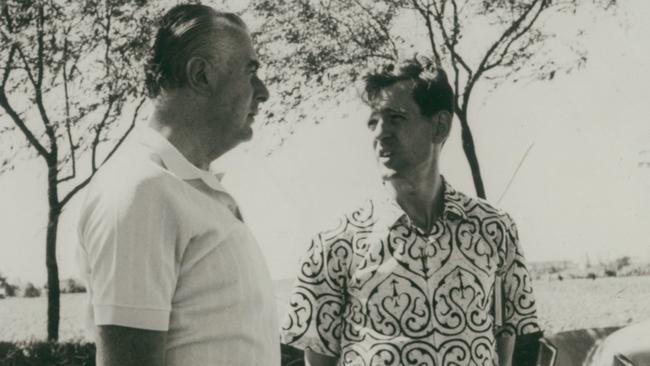

The aspiring PM’s meeting with enigmatic Chinese premier Zhou Enlai forged strong ties.

In April 1971, Gough Whitlam asked me to urge Beijing to invite him for talks on China-Australia relations. Whitlam saw a chance to push the China issue – and win power as prime minister – in Beijing’s apparent 1970 decision to discontinue wheat purchases from Australia and give the orders to Canada instead.

Whitlam thought Australia should have as good relations as possible with all four powers that dominated Australia’s region: US, Japan, China, and the Soviet Union.

Whitlam possessed the rationality of a bright lawyer; he wanted a logical, solve-all-the-problems Australian foreign policy.

Nevertheless, the Australian Labor Party’s China initiative in the spring of 1971 was risky. Whitlam announced his appeal to Beijing for a visit before he telephoned me to try to make the invitation occur! He seemed more confident than I was that I could pull a few strings.

I knew the French ambassador in Beijing, Etienne Manac’h, from interviewing him in Paris about Vietnam while on assignment for Atlantic Monthly. I explained to him that Labor’s policies on Vietnam and China were close to France’s; could he smooth Whitlam’s path to Beijing?

Ambassador Manac’h involved Premier Zhou Enlai in the matter, via the senior diplomat, Han Xu. I soon received a cable from Whitlam that read simply, “Eureka. We won.” He was invited to Beijing for talks with Chinese leaders. One half of me thought Whitlam would succeed in his diplomatic mission; the other half feared he might fall flat on his face.

Whitlam and his aides reached Beijing, Chinese Foreign Ministry officials and I met their plane. Whitlam emerged in a blue suit and said to Zhang Xiruo, head of the Chinese Institute for International Affairs, host to the Australians, “I have been looking forward to meeting you.”

Whitlam’s group, now including me, stayed at Beijing Hotel. Following talks with various ministers, one evening we were told by our hosts not to leave the hotel. A film was to be shown that we would find “very interesting”. Soon after 9pm a phone call came: the movie was off. A meeting at the Great Hall of the People was on.

Zhou warmly welcomed his Australian visitors to the East Chamber, with its high ceilings, leaping murals and crimson carpets. Present also were Ji Pengfei, the foreign minister, and Bai Xiangguo, the trade minister, both of whom we had met in previous days.

Zhou was slight and handsome, with expressive hands and a theatrical manner. He was all in grey except for a red “Serve the People” badge, black socks inside his sandals and black hairs amid his grey ones. Sitting in his cane armchair, Zhou was a loose-limbed willow of a man. By comparison, the tall Whitlam, hunched over in his chair, seemed stiff as a pine.

Zhou flattered me by saying, with a finger pointing toward my chair, “This man came to Beijing as your vanguard officer!” In fact, I was not quite a vanguard officer for Whitlam. However, I was a Beijing-lured “vanguard source” for Zhou’s staff as they prepared for Whitlam.

Whitlam gave a good account of Australia’s foreign policy, but he showed little understanding of the impact of the split between Beijing and Moscow. The premier spent minutes criticising former US secretary of state John Foster Dulles for his policies of “encircling China”.

He reached for his tea mug, sipped and swilled with deliberation. Then he went on, “Today, Dulles has a successor in our northern neighbour.” Whitlam said, “You mean Japan?” This revealed how unprepared Whitlam was to grasp the strategic shift that had occurred in Chinese thinking. Zhou was curt in response: “Japan is to the east of us – I said to the north.” It was hard for anyone on the Australian left to accept that Mao’s CCP might think of the Soviet Union as an enemy.

Zhou was just as tough on Japan. He feared the Nixon Doctrine. Asking more self-reliance from America’s allies in Asia would turn Japan into America’s “vanguard in East Asia”. He said it was “in the spirit of using Asians to fight Asians”, or, involving Australia, “Using Austral-Asians to fight Asians.” He feared Japan would develop nuclear weapons.

“Look at our so-called ally,” Zhou said to Whitlam of the Soviet Union. “They are in warm relations with the Sato government of Japan and in warm discussions on so-called ‘nuclear disarmament’ with the Nixon government, while China, their ally, is threatened by both of these.

“Is your own ally so very reliable?” the Chinese premier dramatically challenged Whitlam. “They have succeeded in dragging you on to the Vietnam battlefield. How is that defensive? That is aggression.”

Later, Whitlam told he me he was surprised Zhou had not raised the issue of American military bases in Australia. In fact, the omission was a sign Mao was no longer as worried about the US as he was about the Soviet Union.

When Whitlam expressed acceptance of the “One China” principle that Beijing asked of foreign partners, Zhou said crisply: “So far this is only words. When you return to Australia and become prime minister you will be able to carry out actions.” Throughout the evening, Zhou never mentioned trade or uttered the word “wheat”.

The following day People’s Daily published a photo of our Australian group. Chinese officials made it clear that important business had been done with the Australian side, though only to be consummated by political change in Australia.

Whitlam’s fairly skilful performance with Zhou, Foreign Minister Ji, and Trade Minister Bai ensured that the China issue would propel him nearer to election as Australian prime minister. It also set in motion new thinking among Australians about China.

In the early 1970s, in the view of many people in the US, Australia, and other countries, when the torment of Indochina finally ended, the West would have to share the future in Asia with China. Whitlam began a modest contribution to this turning point.

This is an edited extract from Ross Terrill’s Australian Bush to Tiananmen Square (Hamilton).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout