Fifty years ago China was a secretive and foreboding place. Perceptions of China were framed through the lens of fear and hostility. Today China is viewed as a rigidly authoritarian and increasingly assertive country that again arouses paranoia and distrust, some of it justified given economic coercion and foreign interference.

The Lowy Institute Poll reveals that 63 per cent of Australians, a clear majority, now view China as more of a “security threat” than an “economic partner”, which was the view of just 34 per cent. Three years ago, 82 per cent saw China as more of an economic partner whereas only 12 per cent saw China as a security threat.

In the past decade China has expanded its influence with an aggressive diplomatic network and trade and infrastructure agreements such as the Belt and Road Initiative. It has militarised contested islands and sea lanes in the Asia-Pacific and denounced any nation that disagrees with its belligerent approach.

While Australia has been punished with trade sanctions for a range of grievances, such as banning Huawei from the 5G network and calling for an inquiry into the origins of Covid-19, we are not alone. Hostile perceptions of China also have risen in most Western nations and among Association of Southeast Asian Nations countries.

Asked who is to blame for the rapid deterioration in the Australia-China relationship, most Australians (56 per cent) say China is more to blame but a significant number (38 per cent) say both countries are equally to blame, according to the Lowy Institute Poll. Only 4 per cent say Australia is more to blame.

It may be that in the long run China has damaged its international standing and reputation. It has united the West. While Donald Trump trashed US alliances and multilateral institutions, Joe Biden is rebuilding them. The G7, NATO and the Quad – US, Japan, India and Australia – are now focused on the China challenge.

But most countries in our region have found a way to engage with China to their benefit. This includes Japan, which has deep-seated grievances with China, and Singapore, South Korea, The Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam. Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong made this point when he met Scott Morrison recently.

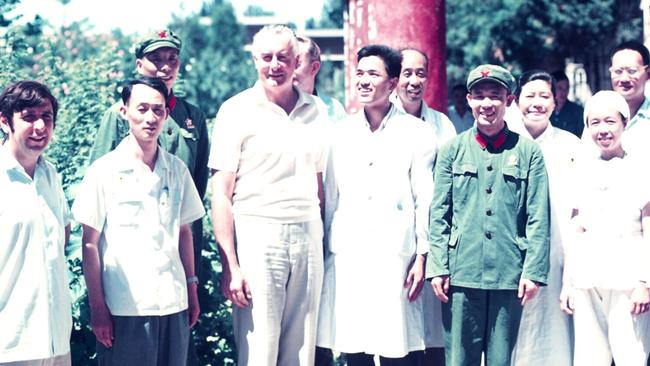

This is the pragmatic, rational and realpolitik approach Whitlam brought to the Australia-China relationship. In a series of articles for The Sunday Australian, the then opposition leader explained why he wanted Australia to engage with China. He did so just as US president Richard Nixon outlined his grand strategic gambit of opening to China, led by US national security adviser Henry Kissinger.

Whitlam urged Australians to be mature and self-confident to deal with China as it was. “The Australian people should come to terms with the realities of our situation and our future in this region,” he wrote. He did not expect to have “great influence” with China, nor did he think Australia had to choose between the US and China. But he did see the enormous economic opportunities for Australia that continue to underpin our prosperity. But today Australia is out in the cold. Our ministers and diplomats cannot get high-level meetings or their phone calls returned.

Other than waiting for relations magically to repair themselves, neither the government nor the opposition has articulated a comprehensive, coherent and convincing policy strategy for dealing with China. We can gain respect by standing firm on our values but tone down the rhetoric and seek opportunities for dialogue and economic co-operation. We could do with a dose of Whitlam-Nixon realpolitik.

Former ambassador Stephen FitzGerald, who was part of the Labor delegation to China in 1971, told me relations are at their lowest point in 50 years. FitzGerald suggested back-channel discussions could lead to high-level meetings. It is an idea that has merit, provided the right envoy can be found. Perhaps a former minister (Gareth Evans or Alexander Downer) or prime minister (Paul Keating or John Howard) might help thaw the deep freeze.

Through Whitlam’s middle-power diplomacy, Australian perceptions of China changed dramatically. The visit 50 years ago served to demystify the Middle Kingdom and began to shift attitudes. The relationship grew rapidly with new trade agreements and cultural and education exchanges forged by the Fraser, Hawke-Keating and Howard governments. Even today, Australians have a different view of Chinese people than they do of Xi Jinping’s government.

While Australian views of China have worsened in recent years, 85 per cent of Australians remain positive about Chinese people and 79 per cent have a positive view about China’s culture and history, according to the Lowy poll. It is worth remembering that 1.4 million Australians of Chinese heritage live in Australia.

We will not be able to change China. The belief, held by generations of political leaders, that economic liberalisation would lead to greater political freedoms was misplaced. So, we must deal with China as it is. In the final analysis, it is not in our interests to be in China’s diplomatic freezer and losing valuable markets for trade, and unable to advocate our world view and better understand theirs.

This does not mean we have to kowtow to China. Neither did Whitlam, Bob Hawke or Howard who each took the Australia-China relationship to new levels. But we do have to find ways to re-engage with China rather than ignore it. Our economic prosperity, in large part, depends on it. Which is why we urgently have to repair the diplomatic relationship.

The China that Gough Whitlam visited as opposition leader in 1971, which led to diplomatic relations when Labor came to power the following year, is a very different country to the China of today. There are, nevertheless, parallels and lessons for policymakers in how to deal with this growing economic and military power in our region.