The PM’s soft leadership style may have suited 2022. Is it still fit for purpose?

A deeper, more bleak and pessimistic mood is demanding a different political response. Anthony Albanese now faces a dilemma.

The Prime Minister is caught between competing sectarian interests and events that are challenging the government’s claim to competency.

The question facing Labor is whether this is simply the burden of midterm incumbency or a critical failure of policy and political management. Answering this will require an honest and sober self-assessment at all levels of cabinet.

On the economy, housing, immigration, living standards, national security, defence, community safety and now a collapse in social cohesion, Albanese risks the Coalition’s charge of weak leadership gaining traction.

There is no question that the election environment has shifted significantly since the beginning of the year. A deeper, more bleak and pessimistic mood is demanding a different political response.

Much of this has been triggered by unexpected events. No one could have envisaged six months ago, for instance, that crime would be a top three issue of concern for voters.

The government’s management of the immigration detainees scandal and domestic discord over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict inevitably has raised questions about ministerial ability and political agility and now poses a test of moral rigour. This is not the budget environment Albanese and his Treasurer had been hoping and planning for at the start of the year.

While the budget does not directly address some of these broader issues, Labor now must include these conditions in its political calculations.

In this context, Jim Chalmers’ challenge next Tuesday has just become more profound. The tenor of the budget inevitably will invite broader judgment on the Albanese government. The consequences for the Treasurer if he gets it wrong are acute.

Above the plethora of issues facing the government, the two that will define the looming election battlefield are cost of living and the housing crisis.

Labor’s grand vision for an election platform built on an economic growth strategy, anchored in the vision of a manufacturing and clean energy revolution, has been met with cynicism.

The parameters that it was founded on have shifted in the past six weeks. Cost-of-living pain looks likely to extend into the election year as inflation proves more tenacious than expected.

But Chalmers and Albanese seem to lack the agility to move with the change in economic circumstances.

Suddenly the smooth glide to May 2025 is under a cloud and the pressure on the Treasurer to deliver a credible deflationary budget has intensified.

Implicit in the statement on inflation and monetary policy by Reserve Bank of Australia governor Michele Bullock this week is a message to Chalmers that he is at risk of handing down the wrong budget.

Chalmers insists inflation is the near-term priority but he is sticking to the script on the growth strategy. He has no choice. Albanese’s Future Made in Australia program was sold as the vision piece for Labor’s second-term agenda. And Chalmers must deliver it.

While the principles of this program have been sufficiently ventilated ahead of the budget, the debate on its detail and delivery has barely begun. It was conceived before the economic and inflation story deteriorated, globally and locally.

The detailed comments in the RBA statement this week on inflation, including its own economic update, have injected a new dose of reality into the equation. The inflation fight is far from over.

And the budget now matters more than the government had anticipated. Bullock’s statement suggests interest rates won’t come down until the middle of next year.

The conclusion is that inflation is higher than the RBA had thought it would be, productivity is lower than what it had been hoping for and real wages are lower, despite nominal wages going up quickly.

As things stand, the interest rate bias is now on the upside. This is a stark difference to where the RBA was a month ago.

Bullock was careful not to aggravate the government before a budget. But any economist looking at her statement would say there is a strong message there for Chalmers.

“I’m conscious that there are budgets coming up,” Bullock said at her press conference following the decision to keep rates on hold for now.

“The point I would make is that the federal Treasurer, Jim Chalmers, says publicly – and he says to me in private – that he does have inflation in his mind while he is thinking about the budget.

“And I think they are all conscious that they want to help us beat inflation so they don’t want to try and add to inflationary pressures. We’ll just have to see what the budget comes out like and then we can think about how that might impact our forecast.

“And as I said, the signs, at least by what’s being said, are that inflation is front of mind.”

The problem is, as with all budgets, Chalmers will have been working on this for six months, with some decisions having been baked in based on assumptions that will have changed in the course of the past six weeks. It’s analogous to trying to turn a freighter mid-journey.

The budget takes time to load up and put to sea and becomes very difficult to steer away from any sudden perils.

Now any hope of a rate cut this year or early next year will depend to a large degree on the fiscal policy response and how Chalmers steers the budget spending profile.

Having been accused of going too early on an economic growth strategy before the inflation problem was arrested, Chalmers has sought to put it firmly back at the front of the government’s pre-budget rhetoric this week.

“It will be a responsible budget, a restrained budget, and it will maintain our focus on that inflation fight,” he told ABC’s Radio National on Wednesday morning.

“There will be help for people with the cost of living, but we’ll make sure that that cost-of-living help is part of the solution and not part of the problem when it comes to inflation.

“There will be spending restraint even as we make substantial investments in the future of our economy.”

On Bullock, Chalmers tried to portray an image of the Treasurer and the central bank governor being on the same page on inflation. This will become less credible if the budget doesn’t deliver sufficiently on spending restraint.

Yet Treasury’s inflation forecasts are likely to be more optimistic than the RBA’s 3.8 per cent. This will form the basis of Chalmers’ argument that the budget, in fact, will be deflationary.

But as Paul Keating once said as treasurer: “The proof of the pudding is in the eating.”

“We (Chalmers and Bullock) speak pretty regularly I think as people would expect us to,” Chalmers said.

“We do compare notes on the economy, on the inflation outlook, the outlook for growth, the global situation. And that’s because I really respect the difficult job that Governor Bullock has to do. I believe that she respects the difficult job that I have to do and that we have to do in the budget.

“We don’t tell each other how to do each other’s jobs, but we are on the same page when it comes to getting inflation down because it is inflation which is punishing people.

“And that’s why the progress we’ve made is so important and that’s why it’s so important that we shoot for this second surplus and that we design our cost-of-living policies in a way that puts downward pressure on inflation rather than upward pressure on inflation.”

Chalmers and his colleagues have done little to dampen expectations of rate cuts beginning in the second half of this year. Now this aspiration has been put on hold.

Households will continue to suffer mortgage pain right through to the election. This was not a scenario written into Labor’s re-election playbook.

AMP’s chief economist Shane Oliver said Bullock’s comments put immense pressure on Chalmers over spending.

“But she didn’t say anything about cutting,” Oliver said.

“She’s not ruling anything in or out. The language around that is quite hawkish.

“They’re not having a debate about whether to cut. They’re not saying, ‘Well, what does it take to cut?’ They’re talking about what does it take to hike.”

Chalmers must know he has a problem and that he faces a serious risk of bringing down a budget that is received, and perceived, as being the wrong budget for the times. Interest rates are proving to be a much blunter tool for curbing inflation than was assumed. And without the government helping, it becomes very difficult.

Unlike normal pre-budget periods, the news cycle has been dominated by issues other than the budget. Whether this has helped or hindered Chalmers, who is trying to reframe the government’s economic agenda to manage the disruption of a transition to a clean energy economy, is debatable.

Liberal strategists believe the changing mood and circumstances are tipping more favourably towards Peter Dutton.

While the party’s own pollsters have been trying to soften the Liberal leader’s image, there is a growing view that the times may now start to suit the hard-man image that he has been told to abandon.

There is evidence of this swinging dynamic. The Coalition is back to where it needs to be on core equities. While traditionally it has led Labor on the broader measure of economic management, for the first time it is ahead of Labor on cost of living. This is not a measure that is normally in the Coalition column and largely because traditionally voters have associated cost of living with hand-outs.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor is convinced people are starting to work out that the solutions to the current crisis are more about better economic management.

A similar shift in thinking occurred in the 1980s during the last high inflation period. It was something that Bob Hawke played to with unquestionable success. Taylor would say this was because Hawke was an economist and understood it.

Chalmers, on the other hand, is constrained by internal pressure. Even if he wanted to deliver a significantly contractionary budget, he would struggle to convince the Labor caucus.

But the budget is not the only problem facing the government. An SEC Newgate poll this week showed that crime had featured for the first time in the top three unprompted concerns for voters, behind cost of living and housing.

Crime is now ahead of climate change as a key concern. This is unexpected but not surprising.

The Bondi Junction murders, twin terrorist attacks, rising youth crime in Queensland and the crisis that is domestic violence have become issues of national concern.

The disastrous handling of the High Court’s release of criminally convicted immigration detainees has ensured that the federal government is in the frame.

While not as acute as in the US, Europe or Britain, the domestic manifestation of the Israeli-Palestinian issue – arising from the October 7 Hamas terrorist attack – is also broadening as an issue for Albanese.

The contradicting responses from within cabinet – as displayed by Education Minister Jason Clare’s ham-fisted remarks on the “river to the sea” chant – are also feeding into an image of caucus disunity and division that Albanese is struggling to contain.

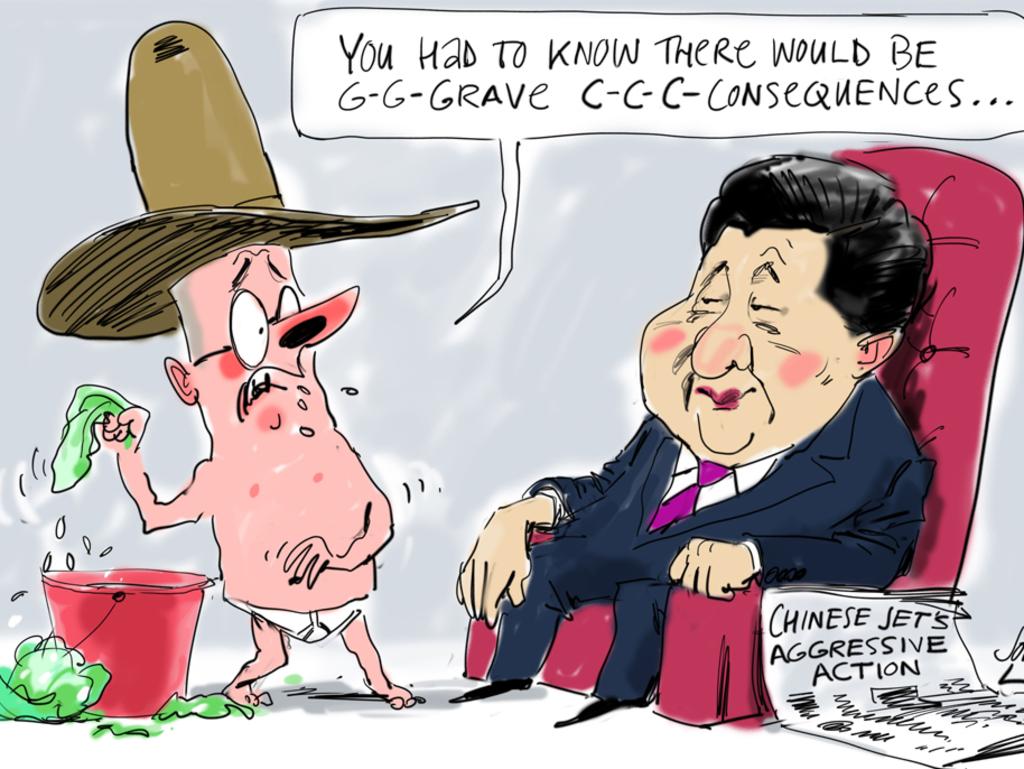

The term regularly being used by the Opposition Leader of Albanese is “weak” – a criticism levelled against the Prime Minister again for his response to last weekend’s incident in the Yellow Sea when a Chinese fighter jet dropped flares in front of an Australian Seahawk helicopter, the most recent display of Chinese military aggression against Australian naval assets.

Until now, this attempt by the Coalition to define Albanese’s leadership has failed to gain traction. But the times are changing and so is the general mood.

The dilemma for Albanese is that he may have boxed himself into a corner with a soft leadership style that may have suited the electoral environment in 2022 but no longer may be fit for purpose.

Anthony Albanese appears to be a leader under siege.