The scale of the Treasurer’s vision is daunting.He correctly sees a new phase of global economic history unfolding – loaded with risks for Australia. The era of free markets and globalisation that Australia exploited so brilliantly with its reform agenda from the early 1980s for a generation has gone into retreat.

What replaces it?

The answer is a far tougher, more dangerous world. Fasten your seatbelts. Chalmers lists the dangers: wars and geo-strategic risks are higher, global growth is slowing, productivity – the driver of living standards – has been weak for decades, inflation has moderated but still lingers, the expansion in industrial subsidies in the main economies has been “stupendous”, markets and supply chains are fragmenting and climate change poses a transforming challenge.

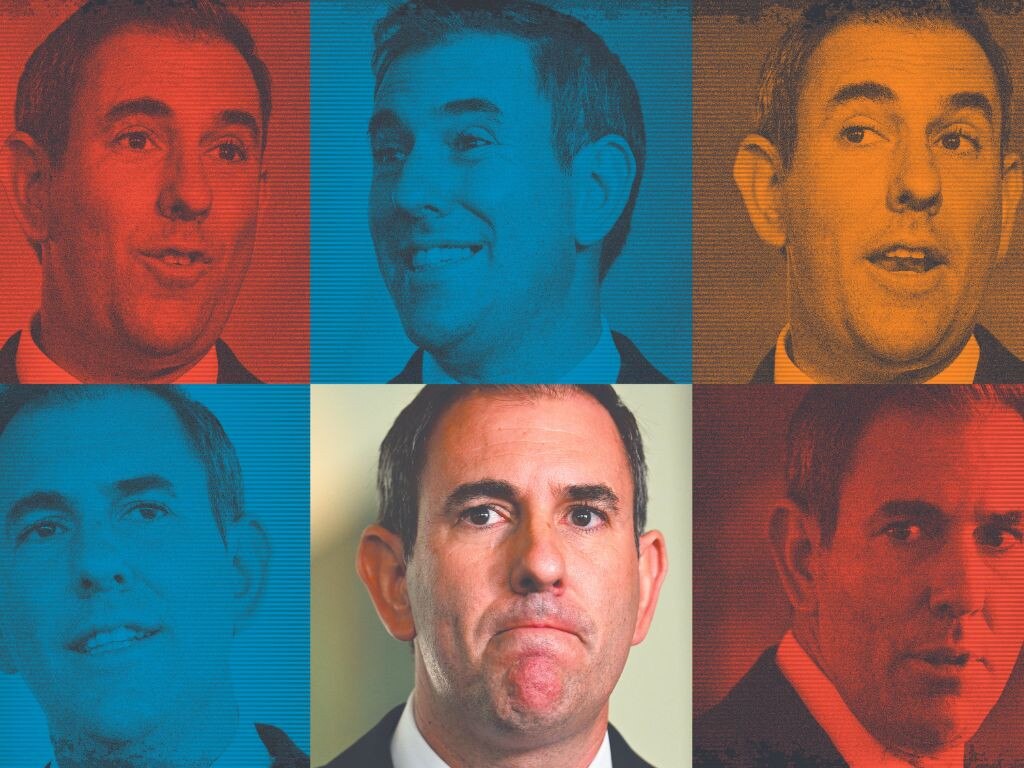

Always keen on the big trends, Chalmers unflinchingly says the global outlook that Australia faces is perilous, fraught and fragile. Yes, this is Australia’s Treasurer talking. Do his colleagues at the cabinet table understand this world? Do they grasp Labor’s fate as a government at this time? More to the point, does Labor know what to do at this hinge of history moment?

In case you are sceptical about its gravity, absorb the message a fortnight ago from International Monetary Fund managing director Kristalina Georgieva, who said “without a course correction” we are “heading for the ‘tepid ’20s’, a sluggish and disappointing decade”. That’s right – the omens point to the 2020s being a bad decade. Georgieva said: “Global growth is weak by historical standards.” And this is not a new story; the deadly mixture was the 2008-09 global financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic. It’s deep-seated.

Georgieva warned inflation was still not beaten; many nations suffered from high deficits and debt. The primary source of the malaise is “a significant and broadbased slowdown in productivity”. But “at this juncture, policymakers face a choice” – leaders can muddle through guaranteeing a substandard and disappointing 2020s or they can strike out for policy boldness and rescue the decade.

Let’s be clear: that’s the choice Australia faces and that Labor faces. But it is compounded by the politics. Australians have no interest in radical change or arduous policy reform. They are still recovering from the pandemic. People are fixated on personal security, financial pressures, health costs, sorting family life, looking after the kids, enjoying their holidays and worrying about retirement. Paradoxically, they look to government more than ever yet distrust governments and politicians. They feel society is fragmenting, that trust is eroding, yet Australians still have the capacity to rally around each other in crisis – witness the Bondi Junction massacre.

Herein lies the challenge of our age – the juxtaposition between the epic challenges identified by Chalmers and the public mood of cautious, unadventurous, distrustful introspection.

The economics and politics don’t fit together. Indeed, they are fighting each other. This tension will make or break the Albanese government.

Having defined the problem, Chalmers, offers the solution – he says Australia in the 2020s must become a “primary beneficiary” from this higher-risk world. We must exploit this “churn and change”. Our worst mistake would be to mark time. The task is to build our economic resilience and his defined agenda is daunting – making Australia a renewable energy superpower, turning net zero into our comparative advantage, integrating economics and security, modernising industry based on cheap energy, refining and processing critical minerals and tapping into critical technologies such as batteries, biopharmaceuticals and artificial intelligence.

But none of this happens without a competitive economy and without better productivity. The vision of transformation sought by Chalmers clashes with on-the-ground reality.

Two years into the Albanese government the economic alarms are ringing. The Reserve Bank strategy to beat inflation is in jeopardy. The best estimate for an interest-rate cut is late 2024 and the worst is the economic turmoil of higher rates. Immigration has been massively mismanaged with annual migration to September last year being more than 540,000, an all-time high, and Labor desperately pledging to cut to a still high 250,000, a level much above the norm.

A range of economists is warning about Labor governments, state and federal, putting more money into the economy and misjudging the fiscal policy settings. KPMG economist Brendan Rynne, in a macroeconomic review, warns of the policy contradiction: Labor spending has added to demand when the Reserve Bank has tried to reduce demand. Rynne said spending now “sits substantially higher than it did prior to the pandemic”. Chris Richardson said in the year just ending Labor’s financial decisions worsened the bottom line by $12bn or 0.5 per cent of GDP. He says spending now runs at 26.1 per cent of GDP compared with the 40-year pre-Covid average of 24.9 per cent.

Deloitte Access Economics partner Stephen Smith said Chalmers’ task of supporting growth but restraining inflation “is the stuff of budget nightmares”. While welcoming an upcoming second budget surplus, Smith said “the fiscal position looks increasingly dire the further out one looks” and reform was needed on both tax and spending to “shore up” the nation’s fiscal health “for the long term”.

A conga line of economists has criticised Anthony Albanese’s defining “Made in Australia” industry policy, his cardinal response to the new world challenges that Chalmers outlined. Smith said the implementation “will impose economic costs that outweigh the economic benefits” and “the only conclusion is that a ‘Future Made in Australia’ is not an economic policy”. This followed the searing critiques from past Productivity Commission chairmen, notably Gary Banks, and the current Labor-appointed chairwoman, Danielle Wood. Banks said Labor had taken a fundamentally wrong track on productivity – that it was promoting an anti-productivity agenda and that a sweeping policy revision was essential, calling for a “U-turn or at least a detour”.

In his Lowy Institute speech Chalmers tried to reframe the industry policy, an admission of its faulty initial presentation, outlining five tests that would guide the policy, saying some support would be only temporary and specifying two streams for the funding criteria – national security and net-zero transformation.

Meanwhile, this week the Grattan Institute, in a major review titled Keeping the Lights On with Tony Wood a principal author, warned that government and industry “have failed to co-ordinate coal exits and renewables entries”.

The report says there is “mounting evidence” the National Electricity Market “may not be able to deliver enough investment in low-emissions generation, storage and transmission when and where it will be needed.” Sounding the warning, it says: “Ministers have lost faith in the market’s capacity to do this, consumers are unhappy with high power prices, and industry players are increasingly wary about investing because they have been buffeted by frequent and unpredictable government interventions in the market.”

Tony Wood, supporter of the energy transition, makes recommendations to get the country successfully through the arduous coal-closure era and then develop a post-coal model for Australia. But he admits things are “not going well”. Safety margins are eroded, the NEM “was not designed for this world”, the reliability problem is serious and the shift to intermittent generation could cost the consumer and see more blackouts.

Labor faces an array of dangerous policy problems. There are too many and all are frontline politics and economics. They go direct to ministerial competence and the failure of central policy co-ordination.

Chalmers has enunciated the challenges Labor faces in this historical moment – inviting everybody to address the question: is Labor up to the job?

The Albanese government is trapped between its ambitious economic vision of the future and its faltering policy outcomes in the present. While the message from Jim Chalmers is that Australia will master the new world of “churn and change”, the danger is that “churn and change” may actually suffocate Australia.