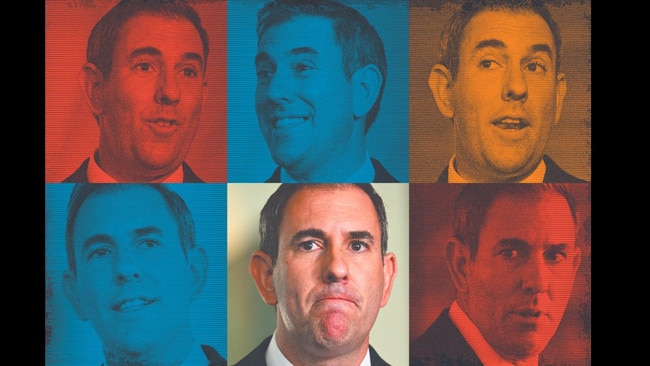

Interest rates put Jim Chalmers’ economic credentials at stake

Monetary policy is not an exact science and opinions differ among economists. But there are two nightmare scenarios for the Albanese government.

The dilemma is diabolical, but mirrors the balancing act across many Western economies. Monetary policy is not an exact science and opinions differ among economists. But there are two nightmare scenarios for the Albanese government – no rate cuts before the election or, far worse, the next move on rates being upwards, not down.

Unsurprisingly, the Treasurer remains optimistic. This week’s figures showed inflation at 3.6 per cent across the year to March, down from 4.1 per cent over the previous quarter. Chalmers said the inflation rate had almost halved since Labor came to power. “It’s still too high,” he said. “But we’re making progress.”

The reality is grimmer. Inflation is getting embedded in much of the domestic economy, risking the best hopes of the Labor Party, the Reserve Bank and the markets. Inflation increased a full 1 per cent during the March quarter, higher than expectations, up from 0.6 per cent in the December quarter.

The final mile in beating inflation will be tougher than many predicted. For Labor, the least worse scenario is the cash rate staying at 4.35 per cent for somewhat longer, prolonging the pain for mortgage holders and further draining political confidence in the government.

Anthony Albanese’s central promise at the 2022 election was to confront the cost-of-living crisis, restore living standards growth and resurrect real wage gains – and he will need tangible proof of progress to win majority re-election.

After these numbers the Reserve Bank will be on alert. Most observers believe it is likely to be cautious, stay its hand and keep its nerve under new governor Michele Bullock. But the “narrow path” the bank has tried to navigate – slaying inflation but minimising damage to the economy – has got narrower still. The bank’s game plan and Labor’s hopes are being squeezed.

Independent economist and budget analyst Chris Richardson tells Inquirer: “This tension in the budget settings has been rising relatively fast but the latest inflation number now makes it pretty red hot. I think there’s a one in five chance there isn’t an interest rate cut before the election. For me, the balance of probability is still for a rate cut in November, late in the year. But it depends how much you poke the bear in the budget.”

Judo Bank main economic adviser Warren Hogan issues Inquirer with a sobering warning: “Domestic inflation is stubbornly high, about 4 to 5 per cent. The economy is looking brighter this year and the tax cuts should provide a further boost. A cash rate of 4.35 per cent isn’t where we need to be and the debate about when to cut interest rates should be off the agenda. I think interest rates need to be at the level where they are in other nations, whether that’s 5 per cent or 5.5 per cent. That probably means two increases in the cash rate this year and maybe a third next year.”

If Hogan is right, Labor’s political strategy will be in turmoil. Rate increases will shatter any sense of confidence in the government and the bank. The political fallout would be vast.

Independent economist Saul Eslake has a very different view. He tells Inquirer: “I don’t think rates will have to increase. The key thing to understand is that inflation is not going up, it’s just not coming down as quickly as some had hoped, including the Reserve Bank. I don’t think there is a good argument for raising rates unless inflation spikes. The answer on monetary policy is that the present settings which are causing some pain will continue for longer than people had previously thought.

“I still think the first rate cut will come in February 2025, in time for the election if the election is held in May next year. I don’t think there’s a good reason for raising interest rates. The inflation surprise we got in Australia this week has occurred in almost every other similar country. The most plausible interpretation of it, is what some central bankers overseas call ‘the last mile’ in getting inflation down – and that’s proving more difficult.”

In his June 7, 2023 speech titled A Narrow Path, former RBA governor Philip Lowe spelt out the bank’s strategy: “That path is one where inflation returns to target within a reasonable timeframe, while the economy continues to grow and we hold on to as many of the gains in the labour market as we can. It is still possible to navigate this path and our ambition is to do so. But it is a narrow path and likely to be a bumpy one, with risks on both sides.”

A bigger bump has now emerged. Domestic inflation is running at a level between 4 and 5 per cent. The main problem is homegrown in the services sector, not overseas induced. The danger is that inflation may start to stabilise in the 3.5 to 4 per cent zone. The big drivers in the recent quarter have been education, rents, insurance and health costs.

Australia’s Reserve Bank has tried to contain inflation with interest rates at a distinctly lower level than in the US, Britain, Canada and New Zealand – an ambitious quest to minimise the damage to economic activity. The question is whether this particular Australian experiment – and it is an experiment – will work.

The answer to this question is at the heart of the differences between economists and is critical to the Prime Minister’s election fate.

Asked whether the Reserve Bank experiment will work, Eslake is positive: “I think there is a better than even chance that it will work. But it won’t be costless because cost of living pressures will persist for longer.”

Hogan, obviously, thinks it has failed. He tells Inquirer: “The longer we allow inflation to become part of the operational nature of our economy, the more we reduce the chances of ridding ourselves of inflation and restoring stability without a recession. This whole ‘narrow path’ concept that has driven policy and perceptions in this country is really trying to pull off something that’s never been done before.

“I’ve only been here for 30 years but I have never seen the narratives coming out of our general commentariat and even our business leadership more off the mark in terms of the economic realities than what we have seen in the past two years. There are no examples in history of an economy being able to get rid of high inflation without a recession.”

Eslake says: “The Reserve Bank made a conscious choice to tolerate inflation being above its target for longer than its peers in the US, Canada, the UK and New Zealand in order to preserve as much as possible of the earlier gains made in employment. This is one reason why the Reserve Bank hasn’t raised rates as much as its peers. I have always thought, therefore, that inflation would be slower to come down here, which it has been.

“I have never understood why the majority of my esteemed peers and the financial markets have been so convinced that rates would come down this year. I’ve never bought that.”

While the economy has slowed a lot, the tax cuts from July 1 are the equivalent of two interest rate cuts in terms of their boost to activity.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor has intensified his attack on the Albanese government, saying: “Inflation is accelerating. Homegrown inflation is running at 5 per cent. The Treasurer cannot hide from this. This is Labor’s inflation. Australians are feeling deep pain.”

Labor is now challenged on the two fundamental economic issues. Beating back inflation has become a more difficult task and Albanese’s growth strategy for the next term, outlined in his Future Made in Australia manifesto, a government interventionist and spending agenda, has provoked a torrent of criticism from a range of economists as a regressive step. Albanese’s timing is revealing. It shows Labor determined to unveil a new economic growth agenda while still battling cost-of-living pressures. Labor can’t afford to be failing the inflation fight but it can’t afford to become a prisoner of that fight.

Richardson doesn’t foresee interest rates having to rise further. He says the risk is rates having to stay on hold for longer. But with growth languishing this year Chalmers reputation depends on devising a credible growth pathway for the next term. That’s the ultimate test for Labor.

Richardson says: “As much as the government would love to have a swing towards growth in the budget, to do something genuine about cost of living they must get on top of inflation. All along they’ve been spending a bit more in budgets, despite what they say, and they’ve been making the Reserve Bank’s task harder. At this stage markets don’t see an interest rate cut this calendar year. If the government throws too much at the economy – going for growth with an election coming – there’s a chance there won’t be an interest rate cut before the election.

“The ability to manoeuvre in this budget has been shrinking for a while. Now it has shrunk dramatically further. If the budget offers support around specific groups, that spending will need to be offset elsewhere. If they do too much extra without offsetting savings, that’s a risk.”

While the public sees cost of living as its chief concern, the corrosion from inflation is pervasive. It means higher interest rates, a higher tax share from wages, while it hurts living standards because wages struggle to match prices. The government’s overriding imperative must be to terminate high inflation.

US Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell recently killed the expected bonanza of six rate cuts this year with the US Fed rate now at 5.25-5.5 per cent with Power, given the resilience of the American economy, happily warning: “If higher inflation does persist, we can maintain the current level (of interest rates) for as longer as needed.” He has no plans to increase rates, but rate cuts this year will be fewer and later.

Deloitte Access Economics partner Stephen Smith says: “Although the quarterly increase in inflation of 1 per cent was above consensus, the downward trajectory remains with annualised inflation coming in well below 4 per cent, having almost halved in 12 months. Today’s figures will see the RBA maintain a cautious ‘wait and see’ posture towards the threat of inflation.

“It also underscores the difficulty of the highwire act the Treasurer must perform when handing down the budget next month, balancing the need to provide cost-of-living relief for households while positioning the Australian economy for a pivot to growth after months of inertia. Without this pivot to growth, investment and productivity will languish, undermining Australia’s medium-term prosperity.”

At stake are Labor’s economic credentials, both in the short term and long term. Chalmers told Sky News on Wednesday that he was aiming for a second budget surplus, the first back-to-back surplus in almost two decades. He said cost-of-living relief would be designed to reduce inflation. He said the May budget would have “a primary focus on inflation” but not “a sole focus” because “we also have this growth challenge in our economy”. He said the budget “will be attentive to both”.

In reality, the main job in the budget is not to do harm, not to make things worse. But if inflation remains sticky with long-delayed interest rate relief from the Reserve Bank, the Coalition will lay a political charge against Chalmers – that he should have done more with fiscal policy over the past two years.

The fiscal reality, however, is that Australia is on a relentless trajectory of bigger government and permanently increased spending.

There are no ifs or maybes – this is deep-seated. The irony of rich Western economies in the 21st century is that the more successful they get, the more demands are placed on government, the more public sector spending grows. The forces driving this trend are immense – they are support for the renewables transition, ageing of the population, growing health costs, weak productivity, pressure to support the disadvantaged (think National Disability Insurance Scheme), reluctance to tackle tax reform and the need to expand defence and security budgets.

Richardson says spending as a proportion of GDP is running at 26.1 per cent as an average across the current four years of forward estimates. That compares with the pre-Covid average over the past 40 years of 24.9 per cent as a proportion of GDP. What is the moral from this? It means Labor should be particularly careful about using budget policy as a stimulus to promote growth.

At the same time, despite the huge spending during the Morrison government to protect the economy against deep recession, by 2022-23 federal spending as share of GDP was back to its previous 40-year average, a result that reflected the impact of high commodity prices, the world giving Australia a pay rise.

Will Labor fall for the most likely trap in the budget? That’s thinking the inflation outlook is better than what it is and going too far in pushing growth. Richardson says: “If you want a rate cut ahead of the election, then your ambitions for this budget are getting smaller by the day.”

Hogan says with the economy seeming to pick up and tax cuts coming “the sooner the Reserve Bank raises rates, the less it will have to do”. On the budget, he warns: “The government has been telling us there’re going to be somewhat disciplined, but unfortunately the government, like financial markets and many commentators, have had the wrong view on the inflation dynamic and misjudged the resilience of the economy.

“Their opportunity to use fiscal policy in a concerted way to deal with this multigenerational inflation challenge was at the start of their time in government. They’ve had a number of budgets now that have shown little inclination to really fight against inflation.”

The long-awaited and politically vital interest rate cuts that Australia needs are now being delayed – being pushed back closer to the election – accentuating the trade-off dilemma faced by Jim Chalmers in his coming budget between resisting inflation and promoting economic growth.