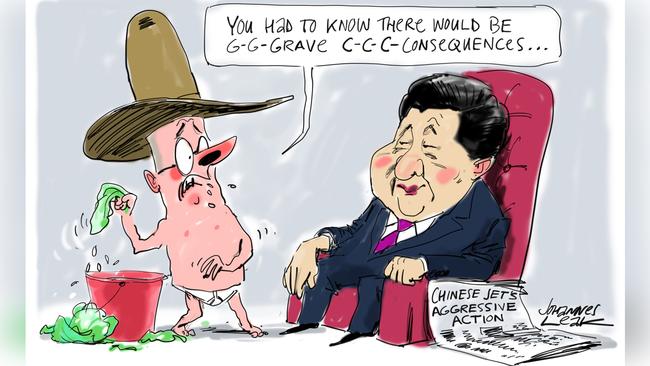

The Australian government’s China policy is not working; it is failing to restrain this dangerous behaviour and limit the risk to the men and women of our Defence Force we are sending into harm’s way.

But this latest episode reveals a bigger problem: Australia’s region is getting much more dangerous – and at a faster rate than we would like – because of an aggressive China. Unfortunately, our response is Defence Minister Richard Marles’s new National Defence Strategy, setting out his plan for the $760bn defence budget over the next decade. A central plank of this plan is that our military will become less capable and less powerful between now and 2034, while others (notably China and its partners) get more powerful.

So, if it’s hard to speak to the Chinese leadership now about defence matters and keep any form of self-respect, it’s only going to get harder. It’s also going to get harder for Australia to play a constructive role in collective defence activities with our partners and allies, who are also facing Xi’s increasingly China.

To turn this around, we need a new plan for our military that acknowledges geopolitical reality. We need to emulate the rapid growth in military power achieved by Japan, Poland and Ukraine. But this is not Marles’s strategy.

Following the May 4 helicopter incident the Chinese government blamed Australia and played the victim. This was entirely predictable.

Beijing denied endangering the lives of helicopter aircrew, while simultaneously insisting the Chinese fighter pilot did the right thing, claiming our helicopter was trying to observe the People’s Liberation Army training.

The fact that even the Beijing spinmeisters admit this latest incident was not in Chinese waters or airspace is inconvenient for them.

But it’s not as inconvenient as the pattern of similarly dangerous behaviour by China’s military in international waters. Back in May 2022, another Chinese fighter jet released chaff in front of an Australian P-8 patrol aircraft over the South China Sea, knowing if it got into the plane’s engines, it could crash.

In late 2022, a Chinese warship used its laser on an Australian patrol aircraft in the Arafura Sea off Darwin, endangering the aircraft and its crew. And there’s the infamous sonar incident in Japan’s exclusive economic zone in November that injured an Australian diver trying to make our frigate safe, which our Prime Minister seems to have thought best not to mention in his face-to-face meeting days later with Xi. It might have distracted from the stability he was achieving in getting Aussie wine back into China.

The Philippines coast guard and navy have many more alarming examples of Chinese military violence and aggression, as do the Canadians, the Americans and the Vietnamese. No spin can obscure this to anyone paying the faintest attention.

Unfortunately, the Australian government is also behaving entirely predictably in its handling of the May 4 incident. It is eerily similar to what Anthony Albanese, Marles and the departments of Defence and Foreign Affairs did back in November, only just a little faster this time.

Step one is a media release addressing how unprofessional and unsafe China’s military conduct was. This has been followed by interviews from Marles and Albanese, repeating these lines and noting the government has been “making appropriate diplomatic representations”. That turns out to be a phone call from DFAT to China’s Canberra embassy. No need to trouble ambassador Xiao Qian by getting him to come to DFAT.

When this looked bad to the public, Albanese told us not to worry: he’d raise the incident with Chinese Premier Li Qiang if he visits in June. That’s a move that looks designed to defuse domestic criticism of government inaction. It also signals to Beijing that the incident isn’t important enough to raise with anyone who matters anytime soon.

If the Australian government is serious about our regional security, it needs to be more serious in how it decides to combat this dangerous pattern of behaviour.

This must involve our PM and Defence Minister using all the levers they have – including direct phone calls and meetings in times of urgency and crisis like the one last weekend. We need to back our words with actions and strength.

If protecting the lives of our Defence Force personnel matters, then let’s see a Chinese military attache expelled when it happens again and the Chinese pilots and commanders sanctioned. Let’s also have Albanese and Marles speaking directly with their Chinese counterparts.

To really shift the dial and help make Australians safer in a more dangerous world, this must be backed by a credible plan, with actions that grow our military power quickly and let us use that power to work more closely with the partners and allies who share deep interests in deterring and restraining China. Let’s change the playbook to one that can work.

Michael Shoebridge is director of Strategic Analysis Australia.

The latest act of aggression by China’s military against Australian defence personnel – dropping flares in front of a navy helicopter – showed us two things. Xi Jinping is happy to see his fighter pilots and ship captains behave in ways that will, at some point, kill our and other militaries.