The inside story of how Australia won the West over on China

Previously unreleased material reveals the former PM’s actions behind the scenes and ‘Australia’s two years of hell.’

“We need multiple points of pushback on this increasing aggression,” Morrison told his most senior ministers during the NSC meeting. The cabinet committee was meeting virtually but was provided with an oral update on the latest Chinese-sponsored cyber activity that was alarming the prime minister.

Morrison was supported by then treasurer Josh Frydenberg, who told the NSC that while China was a great source of economic prosperity for Australia, it was beginning to behave like an adversary power. The PM and treasurer had a common view – Australia must be consistent in its stance against China and deny Beijing the tactic of shifting the goalposts in every bilateral dispute – otherwise the game would be lost.

As early as February 2020, the Morrison cabinet had been briefed on the strategic implications of a global pandemic – the assessment being that China would be empowered, even if only temporarily, and that Australia should expect more cyber attacks and growing militarisation in the region.

The April 20 NSC meeting revealed Morrison’s view that Australia had placated China too much in the past. His message was that Australia must hold its ground, stand up to China, push back when necessary and urged his senior ministers to resort to more assertive language in response to Beijing’s tactics.

The timing of this meeting was significant. It came the day after then foreign minister Marise Payne had given her explosive interview on the ABC Insiders program when she called for an international inquiry into the origins of Covid-19 that had arisen in the central Chinese province of Wuhan.

Payne targeted Beijing, saying the key issue was “transparency from China” – prompting a serious backlash against Australia.

The NSC meeting the next day was seen as a decisive moment; it began to map out a plan to address the calls for an inquiry into the virus along with an international diplomatic campaign that would see Morrison engaging a range of heads of government.

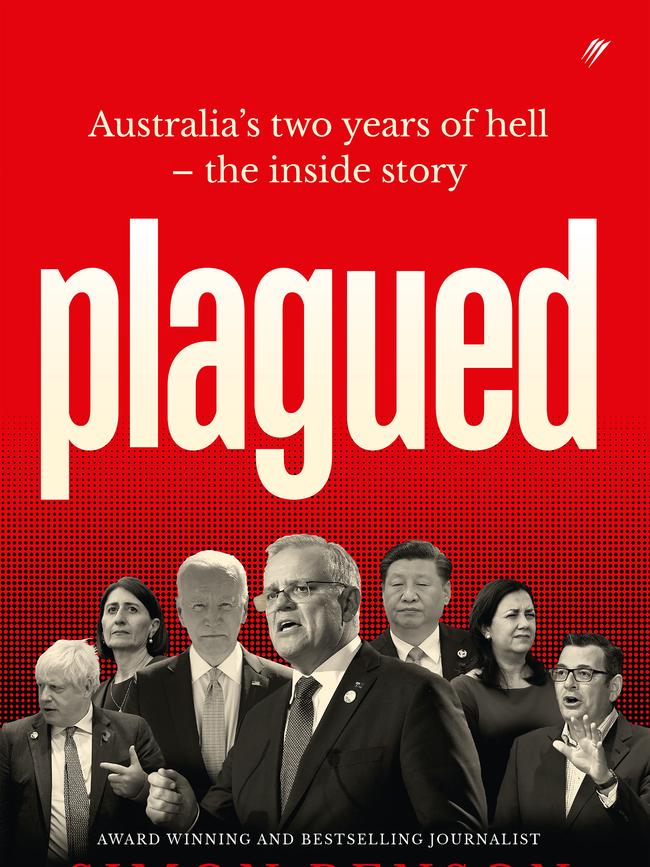

Fresh details and insights into Morrison’s management of China’s coercion against Australia are contained in a new book, Plagued, by The Australian’s political editor Simon Benson and the paper’s chief political correspondent Geoff Chambers.

Drawing upon previously unreleased material involving the NSC, the national cabinet and Morrison’s international diplomacy, Benson and Chambers provide an inside account of Morrison’s policy and political struggle against the pandemic and China’s coercion during what they call “Australia’s two years of hell”.

The portrait painted in the Benson/Chambers book reveals Morrison driving his cabinet and government into a tougher line against Beijing, convinced the world was entering a dangerous geostrategic shift that most Western nations did not fully grasp. Morrison and his senior advisers are revealed to be even more alarmed about China than previously known, and focused at an early stage on the strategic implications of the pandemic.

The book reveals that at an earlier April 6 NSC meeting, the national security implications of Covid were laid out for the first time. The assessment from the nation’s intelligence community was that the pandemic would accelerate tensions in the region and that China could be expected to exploit the situation for its interests.

There were deep concerns about the implications for South-East Asia and for Indonesia where, the authors say, estimates were that “millions” of citizens could die. Benson and Chambers write: “Covid was set to be the most traumatic event since the Second World War for many of the nations in the region. The strategic assessment was that Beijing would see it as an opportunity and could take advantage. It would try to seize the initiative.”

The authors report Morrison told the NSC meeting: “Don’t doubt China’s capacity and will to exploit Covid-19.” He believed Australia would need to counter and fill any vacuum China would seek to exploit. The book makes clear that intelligence assessments about China from Australia’s agencies were instrumental in Morrison’s response.

In my Lowy Institute/Penguin book, Morrison’s Mission, published last year, I quoted one of the highest officials in the Morrison government saying of this situation: “When the PM said this was a fight on two fronts – health and the economy – there was always a third front in our minds: China.”

This April 6 NSC meeting was a fortnight before Payne’s interview on Insiders, and the Benson/Chambers account captures the nature of warnings and discussions among senior ministers. Australia’s scepticism about China’s influence in the World Health Organisation was deep-seated, with Payne saying in her interview the WHO could not conduct the inquiry into the virus since it mixed being “poacher and gamekeeper”.

The Benson/Chambers account explains the Payne interview in terms of her being “despatched to ratchet up the pressure”. Payne’s call for an inquiry was immediately supported by the Labor Party. China’s Foreign Ministry criticised Payne, and its ambassador to Australia, Cheng Jingye, denounced Morrison’s campaign, accused Australia of acting at Washington’s behest and said Australia was risking economic repercussions.

Morrison’s mindset in 2020 was that while the pandemic was an immediate crisis, it would eventually recede – yet China’s ambitions would be an enduring strategic challenge for Australia long after Covid. For the Morrison government, China’s behaviour during the pandemic merely confirmed the pre-pandemic assessment the intelligence agencies had made.

In early 2020, cabinet secretary Andrew Shearer and the secretary of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Phil Gaetjens, were briefing senior ministers on China’s likely response to the pandemic. On February 24, Gaetjens briefed cabinet on a planning document which Shearer had advised on and had been in development since before the pandemic.

Gaetjens characterised Covid as a “stress test” in bilateral ties and predicted Australia could expect friction from China. The view was that Beijing would continue its coercive activities internationally. Morrison raised in cabinet the mood of the Australian public towards China. The authors write: “He felt sure it was one of both concern and acceptance that Australia was exposed. He reiterated a long-held view that it remained important for Australia to diversify its trade relationships and deepen strategic partnerships.”

Morrison said it was “critical” for the government to find ways to support the Australian Chinese community while, at the same time, working more closely with the US through the Indo-Pacific as well as the EU to counter any supply-chain threats.

The PM said he was fully aware that some agricultural industries would be exposed and their businesses risked becoming collateral damage from Australia’s strong stand against China. “We will cop some pain but we can’t let it undermine our national security,” Morrison told cabinet.

The authors report Morrison now believed everything had changed with the ascent to the leadership of Xi Jinping – it was China that had changed but, they say, Morrison felt Australia “was perhaps the first country to appreciate it, understand it and take action against it”.

However, Morrison was anxious to correct what he saw as serious mistakes by many critics – their claim that Australia was just following the US on China policy. Morrison said: “Our reasons for doing what we are doing are often quite different than what America was doing. We are not engaged in some geostrategic competition with China. We are just protecting and advancing our own interests in this part of the world.”

The reality, however, is that this national interest design was intimately tied to the US and other democracies. It was during the April 6 NSC meeting that Morrison raised an idea that would dominate his thinking – using Australia’s invitation to attend the coming G7 leaders meeting involving the US, Britain, Japan, France, Germany, Canada and Italy to leverage our concerns about China. He wanted a stronger collaboration of like-minded democracies that shared the same world view.

Morrison had concluded the only way to counter China was through greater intelligence and strategic co-operation among aligned democracies. He moved to implement this view after Payne’s interview, and the April 20 NSC meeting ended with Morrison saying: “I’ll call the UK Prime Minister.”

But with Boris Johnson out of action with Covid, Morrison on April 21 rang then German chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron – the response being hardly satisfactory. They favoured an inquiry into the origins of the virus but their priority was fighting Covid in their countries. Undeterred, the next day, April 21, Morrison rang then US president Donald Trump.

The Benson/Chambers account has Trump telling Morrison of China: “They could have stopped this. But they didn’t. It’s worse than a depression. Countries are cracking.” The authors report Morrison raised his proposal “for an independent weapons inspector-type role for the WHO” saying that “global organisations like the WHO had been held to the lowest common denominator and needed greater transparency”.

Before he ended the call, Morrison repeated to Trump the need for allies to hold together in the face of punitive economic tactics like those being meted out to Australia. Trump finished on a personal note. “Your family must be very proud of you,” he told Morrison. “The job’s a little tougher than you thought, I bet.”

The authors report that Morrison was taken aback. They say Morrison “got on well enough with Trump but was wary of his unpredictable nature and his tendency to change topic quickly”.

China was convinced that Morrison and Trump were conspiring to use the virus against it, a view Morrison rejected. There were distinct differences between Australia and the US: while Trump was pushing the idea that Covid originated from a lab leak in Wuhan, Morrison said he had seen no official intelligence from either the US or Australia giving that credence. Trump’s move to withdraw the US from the WHO was not followed or supported by Morrison.

The Benson/Chambers book says that in late April, Morrison was making or receiving calls on an almost daily basis. On April 28, he got a sympathetic hearing from the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, from Dutch PM Mark Rutte and from Canadian leader Justin Trudeau.

On April 24, and again on May 7, he participated in the First Movers Club dialogue based upon a group of nations that had enjoyed success in suppressing the virus. Spearheaded by then Austrian chancellor Sebastian Kurz, it initially included Australia, Austria, Israel, Greece, Denmark, Norway, the Czech Republic and Singapore and saw New Zealand join for the second meeting.

During the first meeting, Morrison sat, late in the evening, in the secure room, talking to other leaders from a large screen on the wall in front of him. He drank from a mug, everyone assumed was tea or coffee, but was filled with beer.

At the second meeting, Morrison pushed his argument for an inquiry into the virus, now arguing that this wasn’t directed at any one country. He said he had written to G20 leaders seeking support for the virus inquiry – now based on a European resolution put before the World Health Assembly.

The Morrison government hailed passage of the May 2020 WHA resolution supporting an inquiry with Australia a co-sponsor. The resolution was weaker than Australia had wanted and China, in the end, took the tactical decision to endorse the resolution.

On May 4, Morrison told the NSC: “Our relationship with China and the deterioration of the wider strategic situation is the biggest challenge in a generation. We can’t be naive. The game has changed in the last five years.” The authors report Morrison’s advice to the meeting: Australia’s alliance with the US would be the ultimate protection; without the alliance, resisting China’s coercion would be difficult.

It was the next year during Morrison’s 2021 visit to Britain – where he attended the G7 meeting and had a three-way meeting with Boris Johnson and US President Joe Biden – that his global diplomacy reached its zenith. The three leaders laid the basis for the AUKUS agreement to provide Australia with nuclear-powered submarine technology.

In Morrison’s briefing to the G7, leaders he spoke to the 14 grievance points the Chinese embassy in Australia had released to the media. The Benson/Chambers account says Morrison made sure all the leaders had a copy of China’s grievances in front of them.

They report Morrison saying: “This is what they are doing. This is what we are dealing with.” He told the leaders Australia would not submit to such pressure and that if Australia did concede, China would then come after other countries.

Plagued by Simon Benson and Geoff Chambers, published by Pantera Press. Out August 16.

On April 20, 2020, then prime minister Scott Morrison told the national security committee of cabinet that Australia’s democratic system was being “infiltrated” by Beijing and that the government must become more strident in its language about China to signal its resistance.