The cadres in control of communist China

Anyone interested in China’s rulers needs to read this important, trenchant and illuminating book.

Who owns Australia? One might answer, its citizens, who elect its sovereign parliament.

Who owns China? The answer to that is less obvious.

Article 2 of China’s state constitution says “all power belongs to the people”.

But Article 1 has already defined the People’s Republic of China as “a socialist state under the people’s democratic dictatorship led by the working class” that is in turn led, of course, by the Chinese Communist Party. The 96-page constitution is replete with proffered rights, but is not even appealable in law, in practice, because its very first article is interpreted as affirming that everything, including the courts, is in the hands of the unchallengeable and unaccountable party.

Anyone interested in China’s rulers needs to read this important, trenchant and illuminating book by one of the world’s most respected experts – who by our good fortune, happens to be Australian.

The historian John Fitzgerald explains in Cadre Country how the English word China remains – for now – beyond Beijing’s reach, since “English is an open and inclusive language which the party does not control”.

However, it’s very different for Chinese speakers since “as far as the party is concerned, it owns ‘China’ … Virtually everything in China with the Chinese word China (Zhongguo) in its title is owned by the party and run by cadres.”

Thus “Zhongguo belongs not to the people of the country but to the cadres that govern them”.

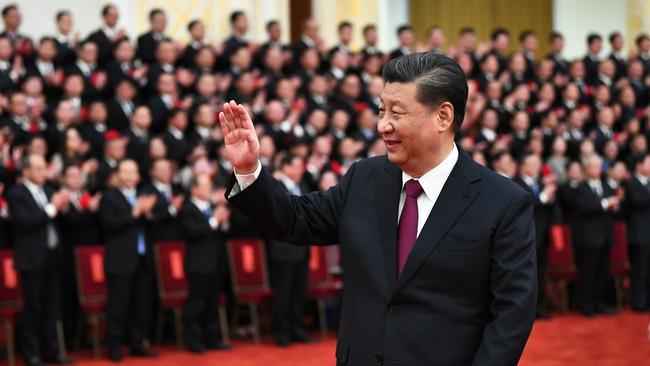

When Xi Jinping declared during the CCP’s centenary celebrations a year ago that “the party has no special interests of its own”, he was – as usual – speaking with sincerity. He genuinely believes that his party incorporates everything that is China or Chinese, although classic Chinese ethnic cultures, at home and abroad, are instead highly individualistic.

The CCP is not a variant on parties like Labor or Liberal in democratic countries ruled by law, but is an entirely different type of entity, which in its ambition for pervasive control, and its emphasis on ideology determined by the leadership – today, Xi Jinping Thought – and on unswerving faith, is closer to a religion.

Discourse control is crucial for the CCP’s aims of omnipotence at home and ensuring the wider world is safe for it. One of the ubiquitous features of this party discourse is that it has “lifted China out of poverty”.

Fitzgerald explains the setting for this: “When the communists took power in 1949 they destroyed much of what they found and claimed what remained for themselves.”

In Deng Xiaoping’s Reform Era – now relegated as the Old Era – “the party leased some of the property it expropriated back to people”.

It was China’s people, Fitzgerald writes, who managed to drag themselves out of poverty knowing the cadres who ruled them would leave them alone if those cadres were allowed to enrich themselves without restraint.

Outside China, this was widely described as a contract – people could get rich in return for their political compliance. However, Fitzgerald says, there was no contract.

“If there was an implicit concession of any kind it worked the other way: allowing cadres to get rich was a small price to pay for the privilege of working your way out of poverty.”

Enter, next, nationalism, which – when it embeds itself in old imperial states such as China – “buries itself so deeply that it appears unique to every country that hosts it”.

Perhaps surprisingly, CCP historians constantly seeking new layers of legitimacy have also sought to confer considerable continuity with imperial-era China.

But as Fitzgerald writes, “there is no place for rational conversation on history”, which is an especially fiercely guarded, taboo zone.

One of the worst thought-crimes in China today is “historical nihilism”.

“References to national humiliation are an everyday feature of patriotic education in Xi’s China,” Fitzgerald says. This was a term first used “in rage against the ruling Manchus for allowing Japan to humiliate the people of China”.

The term had limited currency in China beyond propaganda broadcasts until the CCP revived it in the 1990s.

The late Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo observed that the 1989 military suppressions drove CCP leaders to channel popular enmity from the party towards foreigners. It is now, writes Fitzgerald, “the party leadership’s insistence on upholding the status of the party that accounts for the continuing persistence of the humiliation narrative, not the historical persistence of humiliation”.

Anyone who wishes to command influence in China – including these days even in private business – needs to be a party member.

Of these, fewer than half – 40-47 million – are defined by Fitzgerald as true cadres, or ganbu. They are the Insiders, he says.

The rest of the 1.4 billion population are Outsiders, who can only gaze jealously at the privileged access to education, employment, information and participation in public life enjoyed by cadres, an inequality traceable to relations established at “Liberation” in 1949 between a conquering party and a people conquered.

Rowan Callick, an Industry Fellow at Griffith University Asia Institute, is the author of Party Time: Who Runs China and How (Black Inc).

Cadre Country: How China became the Chinese Communist Party

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout