On China, do we have the courage to look in the mirror?

Australia does not come to its relations with China empty-handed. On the contrary, it brings over a century of historical, cultural and racial baggage.

In the lead-up to the 2022 federal election, then-prime minister Scott Morrison argued that the Chinese government had “picked their horse” for the poll: opposition leader Anthony Albanese. He also described Labor’s deputy leader, Richard Marles, as the “Manchurian Candidate”, drawing on a classic Cold War epithet connoting a puppet who acts on behalf of a foreign enemy, a slur carrying strong overtones of disloyalty and corruption.

Late the previous year, defence minister Peter Dutton had framed China as an enemy with whom this country might soon go to war. He offered the grim warning: “Every major city in Australia, including Hobart, is within range of China’s missiles”, and said that China’s designs on Taiwan rendered it “inconceivable” that Australia would not fight alongside the US in a war over the island.

Critics saw these comments as a classic Coalition wedge of the then-Labor opposition in the fevered climate of pre-election jousting.

But what they did not take account of is the long history of such hostility towards China in Australia, and how both Morrison and Dutton were plucking the strings of these historic anxieties – not necessarily always consciously. They echoed the dread that Asia, and especially China, has evoked in the Australian strategic imagination since the 19th century.

This book is an attempt to chart how Australia, with the active assistance of Beijing and Washington, is swept up once again in fears about the “China threat”.

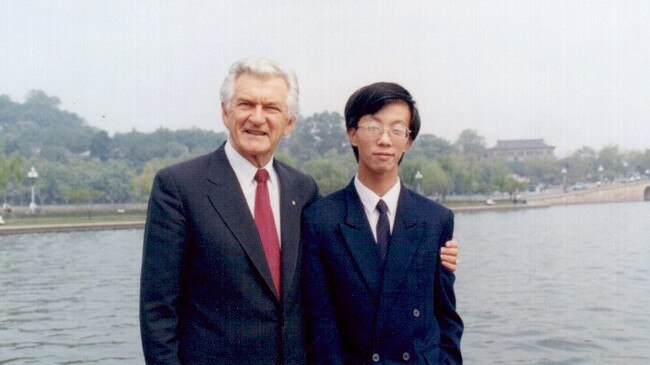

Each prime minister of modern times has put their own stamp on Australia’s relationship with China. But they have all built on, or endeavoured to overcome, underlying cultural and racial influences that have shaped the relationship.

It was in 1893 that the English liberal intellectual Charles Henry Pearson, who had emigrated to Australia, identified China as the greatest potential threat to Western strategic predominance.

He believed that his fellow Australians, who lived on the frontier separating the white and “coloured” races, were the first to raise the alarm and to take measures to hold the line for Western civilisation. His fellow colonists were: “all too aware that China can swamp us with a single year’s surplus of population; and we know that if national existence is sacrificed to the working of a few mines and sugar plantations, it is not the Englishman in Australia alone, but the whole civilised world, that will be the losers”.

At the height of the Cold War, journalist Donald Horne tried to come to terms with the new strategic circumstances facing Australia as it emerged from the British imperial orbit.

In 1964, he wrote in the US journal Foreign Affairs of his astonishment when, arriving back in Sydney from Britain 10 years earlier, a friend had launched straight into a grim prognosis of the immediate future: “How long do you give us? I give us three years.” When I asked him what he was talking about he said that he expected that China would conquer Southeast Asia by 1957 and that Australia would become a Chinese dependency shortly after. He speculated for a while about who the first members of Australia’s Quisling government would be.

Australians have been ringing the alarm bells about China for well over a century. Moreover, they have often seen themselves being ahead of the pack in understanding the dangers posed by China and the kinds of measures needed to resist it.

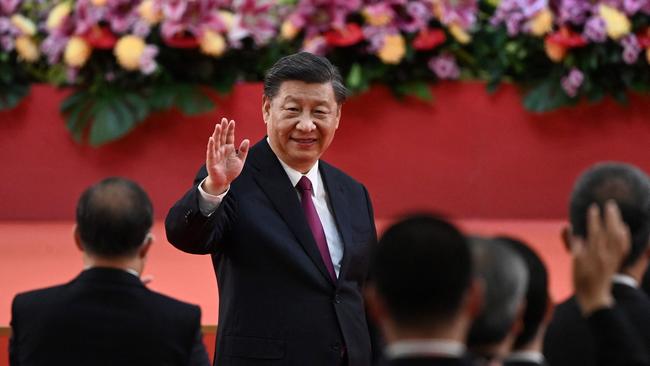

Since 2017, when the sharp deterioration in Australia’s relations with the People’s Republic of China began, some political leaders, influential commentators and analysts have constructed a triumphal tale of Australian resistance to Xi Jinping’s new and unsettling brand of Chinese exceptionalism and authoritarian rule.

This account typically features one or more of the following elements: that China has changed, not Australia, and therefore Canberra has had to draw clear legislative lines concerning political interference, foreign investment and the protection of critical national infrastructure; that “calling out”, “standing up to” and “pushing back on” Chinese intrusion in matters of national sovereignty and trade coercion have made Australia a model for the rest of the world in resisting Chinese pressure; that Canberra’s ability to withstand Beijing’s punitive tariffs on several of its export industries displays a resilience that may mean Australia can safely decouple its economy from China.

The essence of this account stations Canberra on the frontline of a “new Cold War” with China.

This rendition of Australian resilience is habitually accompanied by a soothing saga of reassurance: that Australia’s protector, the US, irrespective of its domestic political upheavals, is now bracing to “have our back” in a long era of “strategic competition” with China; that Canberra’s deepening alliance with Washington has given it new influence in the shaping of America’s Asia strategy and prominence in the global debate about how to confront China; that the formation of a new balancing coalition in the form of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, comprising the leaders of the US, Japan, India and Australia, offers a compelling hedge against Chinese power in the region; and that the AUKUS partnership with the US and Britain, which will potentially see Australia acquire nuclear-powered submarines, will enable it to join with the US and its allies in any military contingency involving China.

The nation’s public debate is alive with journalists and parliamentarians expressing the conviction that Beijing represents an existential threat to Australian security and prosperity; the charge of “appeasement” is again flung with vehemence towards anyone not sharing the same views of the China “threat”. Chinese students studying in Australia are allegedly foreign agents, prominent Chinese Australians have had their loyalty to Australia questioned during public hearings in federal parliament, racial abuse of Asian Australians is on the rise, and public trust in the Chinese government of Xi Jinping has collapsed.

But there are problems with this position.

The first is that it has left future governments with little room to manoeuvre in the making of their foreign and defence policy. Because the China “threat” narrative has become so hardwired into the Australian outlook, because a world without American global leadership is beyond Australia’s imagination, and because Australia has increasingly locked itself into the American grand strategy for Asia, Canberra’s choices have been narrowed, viewed only through the prism of what they mean for countering China’s reach. Thus the Australian foreign policy tradition in place since the end of “White Australia” in the mid-1960s, in which the embrace of the countries and cultures of Southeast and North Asia on their own terms has been central to the pursuit of trust and acceptance in the region, has been cast aside.

This region, vital to Australia’s economic future and defence, has been overshadowed in policymaking by the China threat and is now viewed solely through the prism of resisting Beijing. Moreover, the intensity and perceived urgency with which Australia seeks to confront Chinese influence and pressure have isolated it from its neighbours.

The second problem is the acquittal this story provides to recent Australian governments in their management of the relationship with China. Notwithstanding the legitimate and serious concerns raised by Xi’s growing authoritarianism and his prosecution of an assertive brand of Chinese nationalism, Australia does not come to its relations with China empty-handed.

On the contrary, it brings over a century of historical, cultural and racial baggage in terms of its relations with Asia, and China in particular. Does Australia have the courage to look in the mirror? With the onus for the downwards spiral in relations attributed entirely to Beijing, the debate has short-circuited any requirement for introspection about what the reaction reveals about the roots of Australia’s geopolitical vision and the longer, complex and rich story of its engagement with China since the beginning of formal diplomatic relations in 1972.

Adjusting to China’s rise is the greatest challenge Australian diplomacy has faced since Japan’s revisionist attempts to remake East Asia in the 1930s. The problems arising from Australia’s asymmetry with China, and indeed other countries in the region, are considerable.

Nevertheless, arriving at an understanding of the story of how both countries adjusted to each other from the early 1970s until now is critical.

At issue is whether both sides did enough to cultivate a relationship of substance that could withstand the inevitable strains arising from the meeting of two very different countries with vastly divergent civilisational and cultural backgrounds.

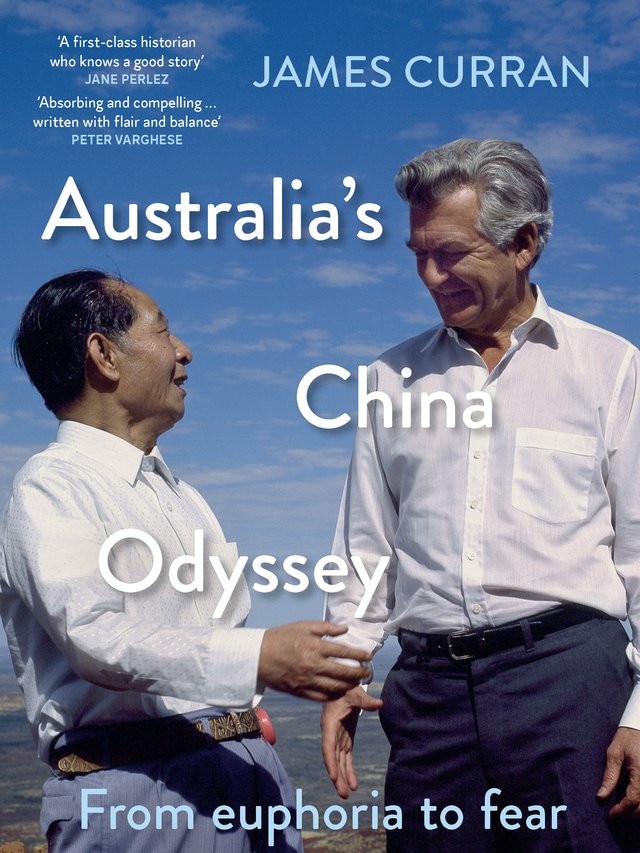

This is an extract from Australia’s China Odyssey: From Euphoria to Fear (New South) by James Curran, professor of modern history at the University of Sydney and a former analyst with the Office of National Assessments.