Taiwan war more likely sooner rather than later

Statements from Beijing and the US raise the real prospect of an invasion within three years.

Last week, two new policy platforms – one from the Washington DC national security establishment and the second from the Chinese Communist Party – offered essential insights into the prospects for war or peace this decade.

President Joe Biden’s National Security Strategy puts the most optimistic case in what is an increasingly bleak strategic outlook.

The statement repeatedly describes the 2020s as the “decisive decade” within which a “competition is under way between the major powers to shape what comes next”.

Notwithstanding Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, Biden’s strategy sees the People’s Republic of China as the decisive strategic threat.

Beijing “is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it”.

Competition with the PRC is global, spanning emerging technology and supply chains. Space and cyber domains is also heating up in competitions for influence everywhere from Africa to the Arctic and Oceania.

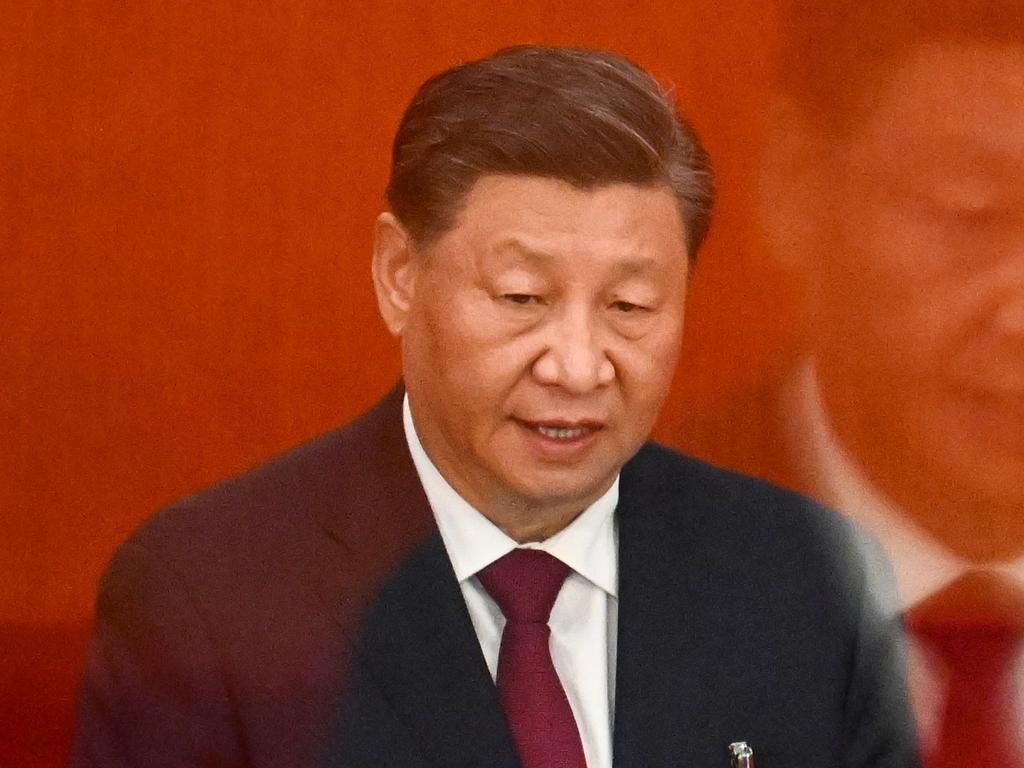

Taiwan is the place where competition runs the risk of turning most dangerously into conflict. China’s intent to take over Taiwan has been declared by the PRC’s paramount leader, Xi Jinping, as “a historic mission and an unshakeable commitment”.

Xi’s two-hour “report” to the Communist Party’s 20th Congress describes “reunification” with Taiwan as “the natural requirement for realising the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”.

This is a commitment to unite “one family bound by blood”, peacefully it is averred “but we will never promise to renounce the use of force, and we reserve the option of taking all measures necessary”.

Xi has just secured for himself another five years as the PRC’s paramount leader. If there is a consensus on any strategic issue in Washington DC today, it is that the risk of a conflict over Taiwan will be at its height during Xi’s third term.

For all of Xi’s calls for peaceful unification, every single action under his leadership has reinforced the hideousness of that proposition for Taiwan and Beijing’s determination to conquer the island and “re-educate” its people.

One of the Biden administration’s more candid public assessments about the timing of a conflict was made last week by Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Speaking at Stanford University, Blinken said: “There has been a change in the approach from Beijing toward Taiwan in recent years … a fundamental decision that the status quo was no longer acceptable and that Beijing was determined to pursue reunification on a much faster timeline.”

That “much faster timeline” leads many in the US national security community to consider the risks of conflict inside three or four years. Last Thursday, this newspaper reported comments from Elbridge Colby, a former senior Pentagon strategist in the Trump administration, asking: “Why are we not on a national mobilisation footing?”

Colby is not an outlier here. Just below the surface of public debate is a near-universal concern among American defence planners that Xi will not be deterred in his determination to take Taiwan sooner rather than later.

Blood and Marxism adapted to “the Chinese context and the needs of our times” are the central themes of Xi’s report to the 20th Party Congress. They form the twin platforms for his third term in power: a means of harnessing popular nationalism and for enforcing rigid adherence to Chinese Communist Party control, which in effect now means Xi’s personal control.

Xi devoted about 1000 words of his report to military modernisation. Three messages dominate. First, the aim is not just to keep to longstanding plans to modernise the People’s Liberation Army by 2027, but rather “more quickly elevating our people’s armed forces to world-class standards”.

Second, the focus of military modernisation is to “deter and manage crises and conflicts, and win local wars”.

Third, Xi repeatedly emphasises that the PLA is the military arm of the Communist Party. Xi’s first defence objective is to “continue to enhance political loyalty in the military”.

Xi promises “no mercy for corruption” in business or the Communist Party itself. “We have used a combination of measures to ‘take out tigers,’ ‘swat flies,’ and ‘hunt down foxes,’ punishing corrupt officials of all types,” he said.

Corruption is endemic in the PRC and the Communist Party. Xi’s anti-corruption drive cements his own supporters in place, culling leadership groups to ensure that no alternative power source can take shape. None of this suggests that Xi plans to offer a more conciliatory face to the international community. His “report” positions him for the most authoritarian period in his long rule.

There are huge dangers for China in this. The risk is that Xi will double down on policies such as the Belt and Road Initiative and harsh Covid lockdowns that are massively damaging the country’s international position.

In Xi’s third term we should expect more aggressive Wolf Warrior diplomacy and expanding military power, all focused on coercing Taiwan if possible and defeating the country if necessary.

This all jars with the more appropriately moderate rhetoric of Biden’s National Security Statement. The core message of the statement is the call to prepare for a decade of competition, sitting uncomfortably with the proposition that the US can selectively co-operate with Beijing.

The strategy says: “On one track, we will co-operate with any country, including our geopolitical rivals, that is willing to work constructively with us to address shared challenges.”

For Biden, this is important to meet his party’s expectation on climate policy, where China’s meaningful participation is essential to deliver any halfway realistic global strategy to reduce carbon emissions. Blinken’s judgment at Stanford University was not optimistic about Beijing’s co-operation: “The world fundamentally expects this of us, so whether China wants to find ways to co-operate or not on particularly climate, global health, maybe counternarcotics, even if they don’t want to, there’s a huge demand signal from the world.”

Biden’s National Security Strategy nods in the direction of the Democrats’ aspirations on climate even as his Secretary of State admits that little progress is likely.

Australia is mentioned a remarkable seven times in the Biden statement, reflecting the administration’s laudable emphasis on working with its closest allies.

The most substantive of these mentions says: “Our AUKUS security partnership with Australia and the United Kingdom promotes stability in the Indo-Pacific while deepening defence and technology integration.”

There are a couple of important messages for Anthony Albanese in this: First, AUKUS isn’t just a favour handed to Australia. It’s a central plank of Biden’s security policy.

Second, AUKUS offers a unique opportunity to be part of an allied defence and technology industrial base. That amounts to a pathway to a more credible Australian defence posture. A failure to make the most of AUKUS consigns Australia to irrelevance in a China-dominated Indo-Pacific.

Finally, our own Defence establishment needs igniting with a firebrand of urgency. The organisation seems suffused with a sense of business as usual calmness. Working hard on last decade’s plans does nothing to position Australia for the crisis years ahead.

When might war break out over the Taiwan Strait? We can piously hope the answer is “never”, but American national security professionals take a more pessimistic view. They know that if deterrence fails, then war is coming.