‘Respect for justice and law’ died with Breaker Morant, Peter Handcock

The shocking allegations of war crimes against some SAS soldiers echo a century-old injustice.

Scott Morrison, announcing the appointment of a special investigator to consider evidence of alleged criminal acts against some SAS personnel in Afghanistan, stated: “It is our Australian way to deal with these issues with a deep respect for justice and the rule of law — but also one that seeks to illuminate the truth (and) seeks to understand it.”

That is a thoroughly laudable aspiration. It is a pity that, for more than a century, these principles have not been applied to another case where Australians at war were accused of war crimes.

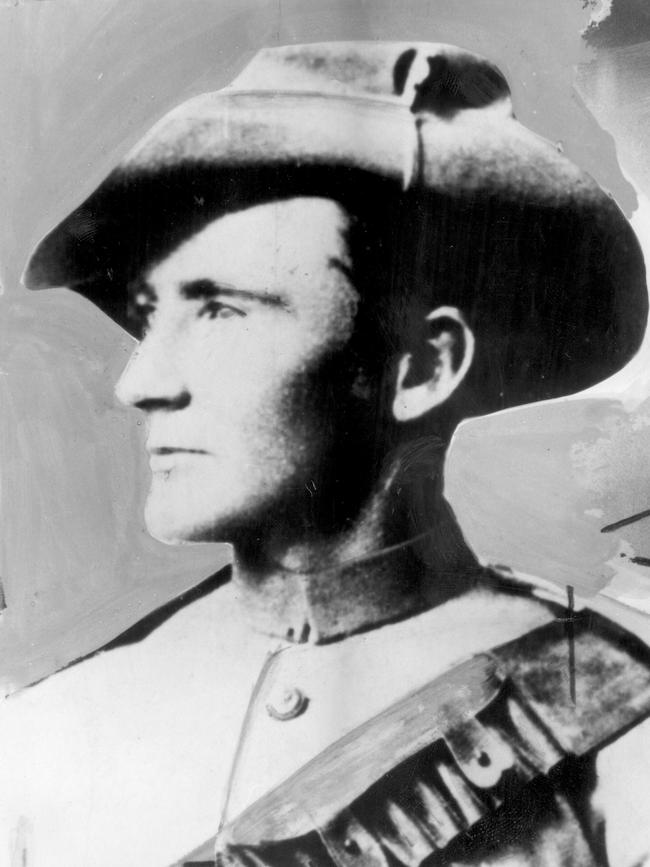

I refer to the still controversial and unresolved matter of the execution of Australian Boer War volunteers lieutenants Harry “Breaker” Morant and Peter Handcock, and the life sentence handed to George Witton in South Africa in 1902. These men were not tried according to the law in 1902 and were denied procedural fairness. That is not merely my assertion. In 2018 the Australian House of Representatives passed a motion to this effect.

Peter FitzSimons’ recent book about Breaker Morant and the Bushveld Carbineers’ murderous campaign against Boer farmers and their families delivers a record drawn from previous writings, historical records, photographs and commentary.

While FitzSimons’ rendition of history provides an understanding of the role that Australian volunteers like Morant played in suppressing Boer commandos, his conclusion that Morant and Handcock got what they deserved overlooks an appalling injustice at the hands of their British superiors.

FitzSimons has failed to critically evaluate the evidence that orders to execute Boer prisoners under the principle of reprisal were given by his superiors. Nor has he properly assessed the evidence that these Australians were not tried and sentenced according to the law of 1902.

The controversy about the treatment of these Australians contains lessons for us in the current situation regarding the accused SAS forces. It remains a stark reminder that holding junior military personnel to account in a stampede of investigation and prosecution permits the deflection of the liability of senior commanders both in the field and at military headquarters.

It allows senior commanders in the field and at home to remain protected and beyond account.

The review of the Morant case in recent times has revealed that the accused men believed they were following lawful orders issued by their British superiors under the law of reprisal.

In the Morant case, the Prime Minister has not yet been convinced that a call for an independent review is justified, notwithstanding a 2018 House of Representatives motion that expressed regret that the men were denied procedural fairness and were not tried according to law.

An opportunity therefore arises from the SAS investigation to apply Morrison’s value of deep respect for justice and the rule of law and deliver to the descendants of Morant, Handcock and Witton a remedy to injustice.

The passing of time and the fact that Morant, Handcock and Witton are deceased does not diminish errors in the administration of justice.

Injustices in times of war are inexcusable and it takes vigilance to right wrongs, to honour those unfairly treated and to demonstrate respect for the rule of law. The Morant matter involves injustice and how we respond is a test of our values and treatment of these Australian veterans.

In light of the SAS investigation, the Morant case provides an opportunity to balance the assessment of allegations of war crimes with the preservation and promotion of the rule to ensure those accused are given the presumption of innocence, proof beyond reasonable doubt and treated in accordance with common and statutory law. Nothing less is unacceptable in a civilised society.

Australians have high regard and respect for our Defence Force and the current war crimes allegations are confronting. However, an equal injustice and affront to Australia’s values is an abrogation of due legal process for political and other agendas.

The trial and sentencing of the three Australians in 1902 is a stark reminder that unless allegations of war crimes are tried according to law, martyrs can be created, and unless military law is strictly followed, a sense of injustice is the result.

In the Morant case, the sense of injustice prevails to this day. These men were not tried according to law for following what they believed were lawful orders.

The liability of senior British commanders was blatant, but the scapegoating of these Australian volunteers ensured that British officers escaped and the executions sent a convenient signal to Boer Command during negotiations to bring a vicious war to an end.

Let’s ensure that the same injustice is not repeated. If Australian commanders in Afghanistan and those in Canberra were knowingly concerned, passively or actively, in aiding and abetting war crimes or showing blind indifference, then they should be held to account to ensure scapegoating of junior officers and NCOs is not repeated.

The culpability of senior commanders, if proven, must prevail despite a temptation to pacify the outrage expressed in public and media arenas. This will need to examine confronting ethical considerations involving officers, including the Chief of the Defence Force, Chief of Army and possibly government ministers.

James Unkles, CMDR Rtd, is a military and civilian lawyer and former crown prosecutor for the commonwealth DPP

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout