From the bush to the Breaker

The Bushveldt Carbineers formed the most disgraced military unit Australians have ever served in.

The Bushveldt Carbineers, raised in South Africa in 1901, were volunteer cavalry, under the command of Lord Kitchener of the British Army. In reality, the Carbineers constituted the most disgraced military unit in which Australians have ever served. Notorious for their indiscipline and contempt for the established rules of war, their most infamous officers were Lieutenant Harry “Breaker” Morant and Lieutenant Peter Handcock.

The Second Boer War (1899-1902) was a simple exercise in British Imperial expansion. The Boer Republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State had consistently resisted British attempts to absorb them into their neighbouring South African possessions. At root, British interests were focused on gold.

The war was as brutal as any guerilla war ever fought. In Major Thomas, author Greg Growden makes it abundantly clear that the absence of meaningful front lines and the frequency of ambush made for warfare in which irregulars could often prevail.

And the Boers were determined and capable fighters. So capable, in fact, that a young war correspondent named Winston Churchill later adopted the Boer term ‘‘commando’’ for elite British troops fighting in World War II.

Growden writes bluntly: “The British weren’t confronting bumbling country bumpkins, but highly skilled marksmen, hunters and stalkers, who would do anything to defend their land.’’

He continues that “the British were soon floundering’’, under siege at numerous outposts, including Mafeking, Ladysmith and Kimberley.

In a horrific seven-day stretch in December 1899, which became known as Black Week, “the British suffered three massive defeats at Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso, where almost 3000 were killed, captured or wounded’’.

Kitchener pushed his army hard, issuing orders that Boer prisoners captured in khaki uniforms were to be shot. Boer civilians were confined in concentration camps. In the savage fighting on the Veldt, with difficulty in telling combatants from civilians, both sides were guilty of war crimes, often on the flimsiest of pretexts.

Harry Morant is often afforded heroic status in Australian folklore. But there are doubts about the man himself: “There is nothing clearly defined about the Breaker Morant story,” Growden writes. “This is hardly surprising as he was a clever, manipulative rogue who knew how to play the perfect upper-class gentleman and the devious low-life. There are many grey areas; even his actual name, derivation and background are open to debate.”

What is not in doubt is that the Bushveldt Carbineers executed prisoners of war. What is also not in doubt is that the arrests and subsequent court martial of Morant, Handcock and Lieutenant George Witton were justified. The verdict, however, remains highly questionable.

Growden focuses his book on the man drafted to defend the Australians. Major James Francis Thomas was a country lawyer from Tenterfield, NSW. Active in his local community, Thomas was also the editor of a local newspaper, The Tenterfield Star, which he owned.

More significantly, Thomas was a militia cavalry officer, and when Britain called upon its colonies to rally to its support during the South African conflict, Thomas was happy to lead part of the NSW contingent into battle.

In Bruce Beresford’s landmark 1980 movie, Breaker Morant, which is an idealised account of the court martial of Morant, Handcock and Witton, Jack Thompson plays Thomas as a skilled and aggressive lawyer.

The facts suggest otherwise. As defence counsel, Thomas gave his best in proceedings that were heavily weighted against the defendants.

But his knowledge of military law and his shifting defence had little impact on uniformed British judges, who were unquestionably hostile to the Australians. Thomas was evidently a decent man, but he was overwhelmed by the forces that were at play in that courtroom.

The outcome of the trial is well known. Morant and Handcock were executed. They lie buried in a common grave in a quiet Pretoria cemetery. Witton’s death sentence was commuted by Kitchener to life imprisonment and Thomas never forgot his incarcerated client.

Ironically, the disciplinary impact of the executions upon Australia was exactly the reverse of what subsequent British military commanders desired.

The infant Australian government in Melbourne originally knew nothing of the court martial and its outcome, and while capital punishment was provided for, in the Commonwealth Defence Act (1903), no Australian government — not even that of the belligerent Billy Hughes — would ever apply it in the field.

British attempts to maintain secrecy over the court martial caused General Douglas Haig endless later fury over his inability to shoot defiant Australian deserters during the Great War.

Growden’s book places another essential literary tile in the mosaic of Australian military history. Morant was a villain and anyone in doubt should read Merv Lilley’s Gatton Man. But his defence counsel was an honourable man. Thomas’s story is worth the telling.

Stephen Loosley is a senior fellow at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra.

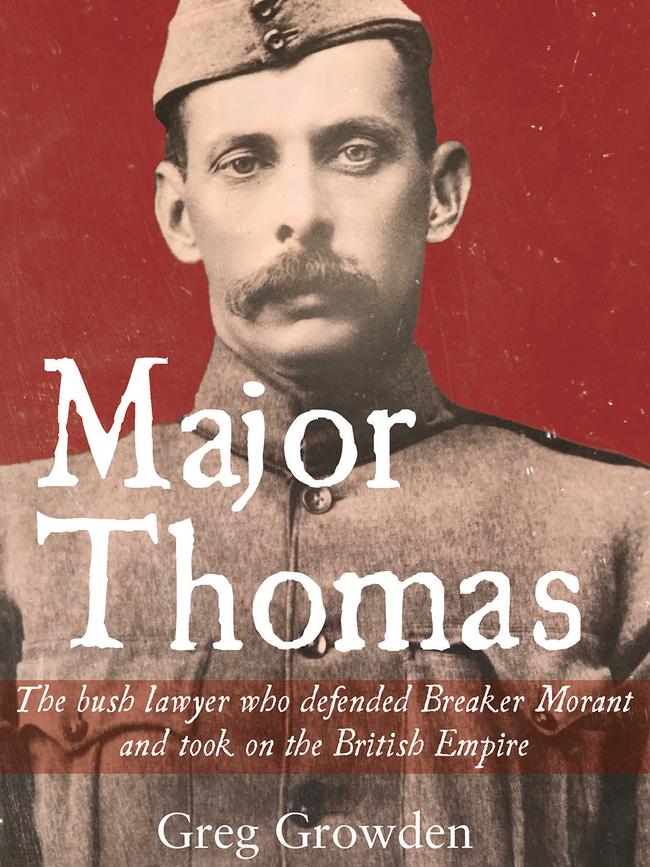

Major Thomas: The Bush Lawyer Who Defended Breaker Morant and Took on the British Empire

By Greg Growden

Affirm Press, 292pp, $32.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout