Peter FitzSimons reveals Breaker Morant as we’ve never seen him

Peter FitzSimons’s new book on Breaker Morant reveals a drunk, womaniser and fantasist and is full of surprises.

As a teenager in the 1950s, I remember reading a number of books by Ion Idriess, who, along with Frank Clune, was one of the two writers that concentrated on Australian characters and Australian history. Nonfiction books such as The Cattle King, The Drums of Mer and Lasseter’s Last Ride were exciting tales about my own country and made me realise that films could be made — one day — that told Australian stories.

Peter FitzSimons has taken over from Idriess with an astonishing output concentrated on key people and events in Australian history: Tobruk, Douglas Mawson, General John Monash, Kokoda, the Batavia wreck, Gallipoli and a number of others. He has now written a gripping 500-plus page epic about Breaker Morant and the Boer War.

FitzSimons is the only celebrated ex-rugby union player I can recall who has become a sports journalist, is chair of the Australian Republican movement, and who has produced a string of best-selling nonfiction works.

As much as I admired the Idriess books, I found the writing style rather ponderous, no matter how fascinating the basic stories. FitzSimons writes in a fluent, accessible style that I am sure has led to him being accused, unfairly, of triviality.

I had to read a large number of books about the Boer War when writing the script for my film Breaker Morant, more than 40 years ago, but not one of them covered the complexity of the war and the characters involved in it, with the depth of research and almost joyous storytelling skill of FitzSimons’s Breaker Morant.

There are detailed descriptions of the battles and horrors of the conflict, balanced by the occasional humorous anecdote. One soldier asked the whereabouts of his amputated leg. On being told it had been buried, he insisted it was dug up as he had £4 in the trouser pocket. The money was returned to him.

The pre-Boer War chapters deal with Breaker Morant in Australia and have a lot of material about him that is new to me. He was a brilliant horseman, a drunk, womaniser, fantasist, untrustworthy with money and a superb raconteur.

He was born in Somerset and was quite well educated. His real name was Murrant (I was unaware of this) but he changed it to avoid creditors and to elevate his social position.

As Harry Harbord Morant, he claimed to be the son of Admiral Sir George Digby Morant of Brockenhurst Park, a grand country house in Hampshire.

When preparing the Breaker Morant film, I was contacted by a number of people, from various parts of Australia, who assured me Morant was once married to Daisy Bates, who later achieved fame when she lived among Aborigines on the Nullarbor plain for nearly 40 years.

No proof was every produced so I made no mention of Morant’s marriage in the film. FitzSimons’s research, however, has revealed that Morant and Bates married in Charters Towers in 1884. They separated a few months later.

The Boer War (1899-1902) is vividly described, based on research done from the British and Boer sides of the conflict. The details are complex but it is clear the basic factor is that the British were intent on taking control of South Africa from the original Dutch, ie Boer, settlers.

Banjo Paterson, who knew Morant well, covered the war in a series of articles for The Sydney Morning Herald. He interviewed Olive Schreiner, the distinguished writer of the classic Story of an African Farm.

“This is all about gold and land,” she told him, “and has nothing to do with liberty, democracy and justice, the things actually worth fighting a war for.”

Apart from the British generals — Kitchener and Roberts — and Boer leaders including Jan Smuts, Denys Reitz and Paul Kruger, there was an all-star cast in South Africa during the conflict. Morant sent reports to the Hawkesbury Gazette, as did Winston Churchill to the London papers. Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling (the latter opposed to a Boer victory) wrote articles, Mahatma Gandhi was a stretcher bearer and Vincent Van Gogh’s brother, Cornelius, fought with the Boers.

The struggle was totally one-sided. About 30,000 British soldiers were fighting about 4000 Boers, most of them farmers. Their horsemanship, marksmanship and sheer tenacity kept the war going for more than three years against an army considered the finest in the world.

“I thought it quite sporting of the Boers”, Churchill wrote, “to take on the whole British Empire”.

By 1900, down on his luck, pursued by creditors, angry husbands and the law, Morant was considering his diminishing options. Another country was appealing. He joined a guerrilla force called the Bushveldt Carbineers that was formed as the war was drawing to a close.

A number of Boer fighters refused to accept defeat and continued sporadic but effective attacks. The Carbineers, which consisted largely of Australians, were commissioned with locating and defeating these groups.

In one battle, the Boers shot and killed Captain Hunt, Morant’s best friend among the Carbineers. Morant was distraught; he vowed revenge and didn’t hesitate to shoot all the Boers he could find, including a number who were prisoners and others, including women and children, who were not combatants at all. He was supported by Lieutenant Peter Handcock, a simple soul whose opinion was that “Boers should all be shot”.

This sentiment was not shared by all members of the Bushveldt Carbineers, which resulted in a formal complaint, signed by 15 men, being sent to Pretoria.

In the trial which followed — the centre-point of my 1980 film — the accused group was defended by an Australian lawyer Major James Thomas.

Morant and Handcock were sentenced to death. Lieutenant George Witton, who was not directly involved in the killings, was given a prison sentence, and a few other Carbineers were acquitted.

A lot of articles and books have been written since the 1902 execution of Morant and Handcock, much of it promoting the viewpoint that they were “Scapegoats of the Empire” (the title of a 1907 book written by Witton). It has been frequently claimed that Morant’s key defence statement — that Lord Kitchener had issued orders that no Boer prisoners were to be taken — is valid.

In 2009, the Australian House of Representatives petitions committee presented a petition to the British crown requesting pardons for Morant, Handcock and Witton.

This was rejected.

Before starting FitzSimons’s book, I felt it likely his position on the trial and execution of the two Australians would echo that of the many vocal groups over the years who considered Morant and Handcock were indeed scapegoats, that Kitchener had issued orders that no Boer prisoners were to be taken and that he thought executing two disreputable Australians who were members of a colonial guerrilla group would stifle criticism.

I totally misjudged FitzSimons’s impartiality in his assessment of the situation. Perhaps I considered his enthusiasm for Australian republicanism would lead to an anti-British stance! He sums up his position succinctly and logically:

I bow to no one in my disdain for Kitchener’s actions in the Boer War — starting with the hideous concentration camps and the policy of burning down 30,000 Boer homesteads. But there is no established link of Kitchener giving orders to kill Boer prisoners — and it defies common sense. How could that be when at the time of the Morant/Handcock atrocities, Boers were surrendering at the rate of 1000 prisoners a month? .... All in all, I think Breaker Morant and Peter Handcock got exactly what they deserved.

FitzSimons’s book includes a large collection of photographs taken during the Boer War, as well as intriguing photos of Morant taken in Australia and England. Incredibly, some memorabilia, which could only have belonged to the defence lawyer Major Thomas, turned up on a rubbish dump in Tenterfield as recently as 2016. (Thomas died at Tenterfield in 1942.)

The collection includes a British penny with Morant’s name etched on it and a faded flag inscribed with the names of Morant and Handcock and the words “this flag bore witness to two scapegoats of the Empire”.

Bruce Beresford is a film director and author. His 1980 film Breaker Morant won 10 Australian Film Institute Awards.

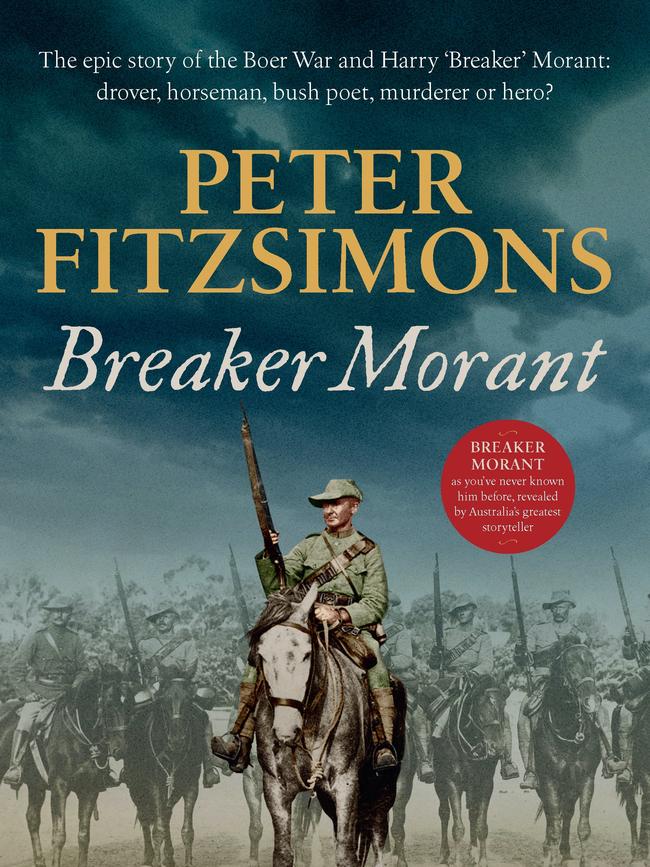

Breaker Morant

Hachette, 547pp, $49.99 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout