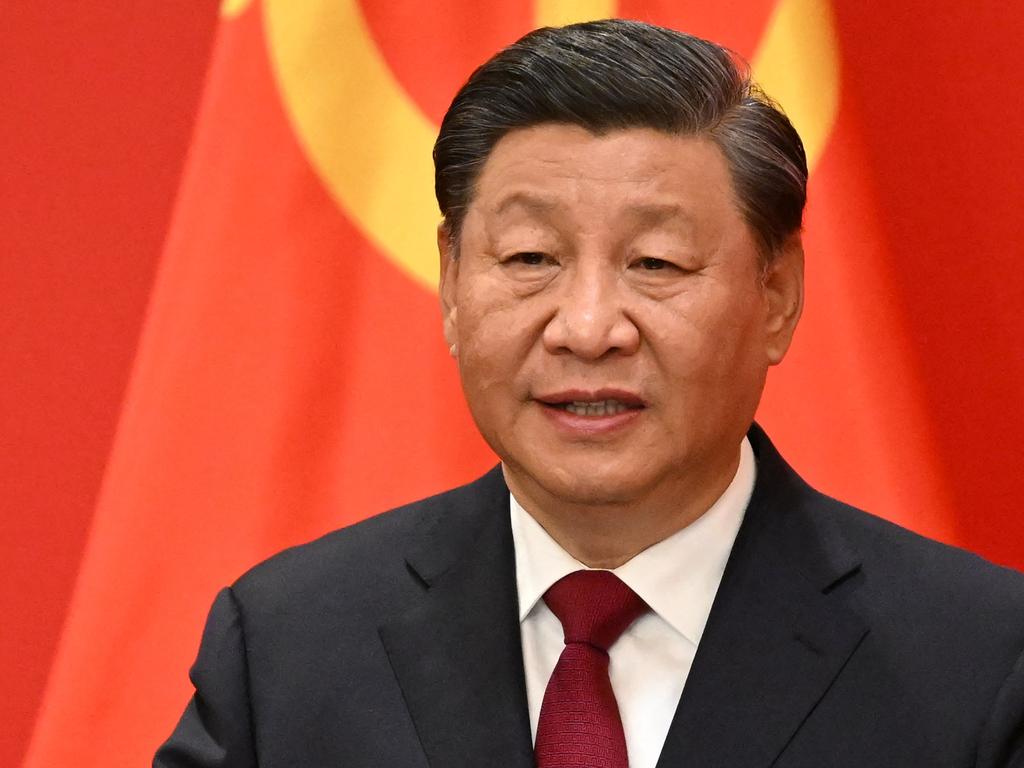

Reality bites Xi Jinping’s dragon ambitions

As China’s leader tightens his grip, his people face increasing economic woes.

On Saturday the 15-day festival for Chinese New Year draws to a close with China’s communist emperor Xi Jinping celebrating the entry of the Year of the Dragon, which traditionally brings greatness and good fortune. The final machinegun echoes of firecrackers to drive out malign spirits will be ricocheting around the waves of high-rise buildings that surround Beijing’s ancient heart.

Xi will be toasting the fact his intimate circle of allies – Russia, Iran, North Korea – is growing tighter and more dependent on China, how in many areas of the global south Beijing’s influence is surging, and how the Western world is riven internally by opposition to its own culture, to liberalism and democracy, and externally by wars in the Middle East, Ukraine and elsewhere.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry shrugged off Alexei Navalny’s excruciating death as an internal affair of China’s “no limits” partner, Vladimir Putin’s Russia – although at least eight of the 14 grievances against Australia issued by China in 2020 involved Australia’s internal affairs.

Most important, Xi will feel on top of the Chinese world. Despite debilitating economic and demographic downturns – dilemmas Kevin Rudd has described as “in large part self-inflicted due to a number of especially poor policy choices by China’s leadership” – Xi is consolidating his absolute personal grip on his party, and the party is intensifying its domination of every corner of Chinese life, from kindergartens to culture to corporations.

Xi’s priorities – and his solutions for China’s challenges – are unaffected by the framings of foreigners. And politics – served loyally by ideology and curated history – are upstream of everything, in his world.

Strength is perceived as a key feature of dragon years, and the ranks of those born in them are replete with the powerful, such as Putin, scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer, business magnate Li Ka-shing and Deng Xiaoping, the dominant figure from China’s reform period that is now characterised as “the old era”.

However, the dragon is, of course, a mythical creature, the only one in the Chinese calendar, and disbelievers may prefer to scorn any optimism surrounding it in the country’s present grim circumstances.

As Foreign Policy deputy editor James Palmer writes: “The 2020s so far feel like China’s lost decade: the economy is slowing down, young people are disillusioned and jobless, and their parents are watching the value of their property crumble.”

My own Chinese friends most commonly describe themselves today merely as surviving. With youth unemployment having reached 20 per cent before the publication of such data was banned, some are tang ping or “lying flat”.

The average annual disposable income of a family in a Chinese city is about $10,000, in rural areas about $4000. To the rising generation – especially in the countryside – the opportunity to catch up with the living standards of neighbouring Koreans, Japanese, Taiwanese and Singaporeans seems to be slipping away. The “golden era” is on hold and people fear they will grow old before they might grow rich.

Many families invested heavily in outside-school tutoring in a throw of the dice to get their children into top universities and thus potentially pull the whole family up a notch. Then 2½ years ago the government banned private tutoring, leaving only the super-rich with the means and methods to boost their children’s prospects.

Xi’s answer to generational anxiety is to delve back into his own Cultural Revolution past as a youth sent down to the countryside where, he says, he found his purpose – in the Chinese Communist Party, of course – and which framed his own determined and resilient personality. This was when he learned to chi ku, to eat bitterness, to persevere without complaint.

And now, he says, “The world has entered a new period of turbulence and change.” So China needs a strong ruler, and – good luck – it has one. “History repeatedly proves that seeking development through struggle promotes prosperity,” he has said, “while seeking security through weakness and concession leads to decline.”

The party flagship People’s Daily says under Xi, “a great Marxist statesman, thinker and strategist”, China is embarking on a “new journey filled with confidence”. For the middle-class generation that has grown up with maids and drivers and cosmopolitan connections, Xi – a theocratic-style leader – is giving them a chance to learn instead from suffering, to chi ku themselves, and to raise their struggle up as a sacrifice on the altar of the party, following his own example. That way lies even greater glory.

As China’s frosty official relations with Australia thawed following the election of the Labor government in 2022, some in Australia began to assume that, more generally, China had been relaxing, forgoing wolf-warrior rhetoric, perhaps even liberalising.

But while many – perhaps most – Australians pursue the minutiae of US, especially Trumpian, politics and rhetoric, chillingly few pay any attention to the relentless governance changes within China and the vast ideological output from Xi’s personal team including an average 12 new books a year.

Even in handling foreign affairs, Xi has pushed the party to the fore, prioritising party-to-party relations – with, for instance, Liu Jianchao, the new head of the party’s international department, who once shared podiums with the disappeared foreign minister Qin Gang as joint government spokesmen, now taking centre stage, including on a recent visit to Australia. Liu’s agency runs a training school in Tanzania for the cadres of six governing southern African parties.

In relating to Australia, the storm clouds have not entirely abated. A month ago China’s ambassador in Canberra, Xiao Qian, warned luridly in this newspaper that if Australia supported Taiwanese independence, “the Australian people would be pushed over the edge of an abyss”.

Beijing’s position has been brought home especially clearly with the suspended death sentence recently handed down to Australian writer and democracy activist Yang Hengjun following a secret trial for alleged espionage, the details of which even Yang may not be fully apprised except from the focus of harsh interrogations.

The core offence, however, is always the same in such political cases, as it was for Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, who died in custody: failing to defer sufficiently and consistently to the absolute authority of the CCP that nurtured and elevated Xi, and will survive him.

But many Australian institutions remain in denial about such unyielding assertiveness or are simply perplexed about how to respond. For instance, the website of the University of Technology Sydney, which awarded a doctorate to Yang, has failed to acknowledge his bleak plight, instead highlighting on its opening page advice on how to “future proof your career” and how to “connect with our Centre for Social Justice and Inclusion and discover new ways to maximise your impact”.

Meanwhile, within China the control of Xi and his party, and their demands on the Chinese people, have intensified inexorably, as these 10 examples show:

Example 1

Universities are abandoning their former separation from party control. Tsinghua, one of the top three in the country, is leading the way, announcing that the administration formerly run by its president (vice-chancellor equivalent) will be fully enmeshed with the university’s party bureaucracy. This shift will intensify the challenges for Australian universities that have strong linkages with Chinese academies, whose structures and goals are becoming ever harder to disentangle from those of the party and thus state.

Jiang Sixian, the party secretary of a top Shanghai university, Jiaotong, has praised a similar “efficient and orderly” merger there, saying the party has “clearer and “clearer requirements” for running such institutions as “socialist universities with Chinese characteristics”.

Political journalist Gao Yu says this is historically innovative: “Now, the whole university must respond to education by the party and integrate politics into the core curriculum.” And the Education Ministry announced ambitiously at its work conference last month that it would pursue “global education governance”.

Example 2

Censorship is becoming even more rigorous. New disciplinary regulations have been introduced that preclude the 97 million party members from possessing, privately reading or even browsing newspapers or magazines, paper or electronic books, internet texts, pictures, audio or video that “adhere to bourgeois liberalisation, oppose the Four Cardinal Principles, arrogantly discuss the party central committee’s major policies or defame the party and country’s leaders, heroes and models” or distort history. Culprits may be expelled and thus usually also lose their jobs. The former head of state-owned banking giant Everbright Group, Tang Shuangning, has been arrested after being sacked from the party for – among other offences – bringing unauthorised books into the country.

Example 3

Ideological evolution is intensifying. Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era has become ubiquitous, required for study by every organisation in China, and every age group.

This cleverly replaces the former Marxist determinant of moral virtue – class – because it has long become apparent to all in China that the sole true source of privilege is the party itself. Xi replaces class with a version of “being Chinese” that he is constantly defining and redefining.

Hunan TV recently screened a five-part dramatised time-travelling series, When Marx Met Confucius, based on a 1925 essay by communist intellectual Guo Moruo, which has gained considerable contemporary currency. Guo has Confucius tell Marx: “Your ideas are systematic and well structured, and they align with my principles.” Thus do the twin greats of the Chinese communist intellectual pantheon jointly endorse Xi’s own socialism with Chinese characteristics.

Example 4

The purges through which Xi came to power, blaming ideological laxity and insufficiently constrained capitalism for corrupting too many cadres, have been institutionalised and extended. Xi has sacked in recent months foreign minister Qin and defence minister Li Shangfu, and nine generals, including five top commanders of the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force that Xi established alongside the traditional army, air force and navy forces.

Fu Cong, China’s ambassador to the EU, attempted to shrug this off: “Personnel change is not uncommon when you see some European politicians also sacked from their positions.” But European leaders don’t tend simply to disappear with no explanation, as in Qin’s bizarre case.

Example 5

Xi has elevated the importance of party belief in itself and in him, its general secretary, expressed through the “four self-confidences”. He has stressed: “We must stay confident in the path, theory, system and culture of socialism with Chinese characteristics. We must uphold the core position of the general secretary” – who is of course himself, the ideological innovator who added the “cultural” self-confidence.

Example 6

Since the CCP has been in unchecked power for approaching 75 years and is the source of all privilege in China, the potentially hostile concept of classic Marxist revolution has long fallen from favour. Xi is instead championing “self-revolution” – involving purges within party ranks, ideological rectification, and self-criticism and self-denial to prioritise the party in one’s personal life. Revealing himself as a master of conservative communist rhetoric, Xi says self-revolution “ensures that the party will never change in quality, change its colour or change its flavour”.

Example 7

Xi is pressing cadres to pursue his “four grassroots” campaign – known as the “four downs” because it calls on them to lower themselves to meet ordinary people and listen to them, make decisions at that level, conduct research there, and promote party principles.

Li Chuncheng, a professor at Fudan University in Shanghai, commented frankly to the South China Morning Post that such goals would remain elusive because “there is no dialogue mechanism in the current bureaucracy”.

Example 8

Xi has consistently focused strongly on renovating and extending China’s nuclear weapons capacity. The New York Times China correspondent Chris Buckley recently unearthed a speech Xi made to China’s top generals in that area, within what was then named the Second Artillery Corps, just 19 days after coming to power in 2012. Xi described their role as “a pillar of our status as a great power” and instructed them to pursue “strategic plans for responding … to military intervention by a powerful enemy”.

Example 9

The authorities appointed by Xi to subjugate Hong Kong – under former policeman John Lee – following the imposition of the national security law on July 1, 2020, continue to tighten the screws and to seek to extend overseas their stern policing of reporting and discussion about the city. Justice Secretary Paul Lam has warned that media may trigger imminent new security legislation by appearing to abet people on Hong Kong’s wanted list – who include Australian lawyer Kevin Yam and resident Ted Hui – by interviewing them, providing them with a platform.

Example 10

International criticisms and sanctions have failed to dent Xi’s intensification of controls over ethnic minorities and people of faith, especially over the Muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang. They are among the key targets of new nationwide regulations introduced on February 1 focused on “sinicising” Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and Taoism to ensure their education programs “cultivate patriotic religious talents”, that they interpret their own scriptures “in a correct manner”, and that they incorporate core CCP and Han ethnic cultural features, including in “architecture, sculptures, paintings, decorations, etc”. Human Rights Watch says “religious venues are to be, effectively, training grounds that promote the values of the Chinese Communist Party to the people” and that in Xinjiang “although some ‘political re-education’ camps appear to have closed, there has been no mass release from prisons, where a half million Turkic Muslims have been held since the start of the crackdown” a decade ago.

But while Xi and his intimate circle remain energetically engaged in intensifying their political and cultural control, the economy is fast faltering. The Chinese leader had believed it to be bulletproof, as it sailed on during the global financial crisis 15 years ago. But that world, too, has changed, the winds have shifted direction.

With domestic consumption – stuck at 53 per cent of gross domestic product, 19 per cent below the global average – failing to rise as hoped, Beijing has returned to manufacturing as its main game, led now by “the new three”: solar cells, lithium batteries and electric vehicles.

Despite success with the new three – for now, although pushback is starting, notably in Europe – China is heading to be overtaken by Mexico as the US’s biggest source of imports, and by the US itself as Germany’s largest trading partner.

There’s industrial overcapacity. Deflation has settled in, as with Japan a couple of decades ago. Foreign direct investment is fleeing rather than fighting to come in.

Global jewellery giant Pandora’s chief executive, Alexander Lacik, told Reuters after a disappointing result in China that to climb back to originally projected returns “it’s going to be a long and tedious journey”.

Government debt has reached 77 per cent of GDP, compared with Australia’s 56 per cent, while government revenue is only 26 per cent of GDP, compared with Australia’s 35.6 per cent. The prospect of overtaking the US’s economy has floated beyond the horizon.

China, including the Hong Kong stockmarket, which has narrowed to becoming just another Chinese equity platform, has lost trillions of dollars in shareholder value in the past three years – in comparison, Japan’s sharemarket has soared 10 per cent this year already – and is seeking to find a floor by returning to stimulus measures, including this week a 0.25 basis point five-year interest rate cut.

But such measures are not expected to reap significant gains beyond the short term, and productivity gains from each yuan spent have kept diminishing and local governments can no longer rely on land sales since the property sector has imploded.

Characteristically, Xi needs to sheet blame on to someone for the share meltdown and has just replaced Yi Huiman as chairman and party secretary of the China Securities Regulatory Commission.

While Xi is applauded for stressing that “housing is for living in, not investing”, 70 per cent of Chinese households have nevertheless invested in property, having been frustrated by all the limited – largely state-dominated – alternatives.

And housing prices have fallen 20 per cent or so in major cities. More than 20 per cent of top office buildings are vacant in Beijing, where most tenants still signing large leases are state corporations. Hong Kong’s High Court recently ordered the liquidation of China’s Evergrande, which a few years ago was the most valuable real estate firm in the world.

Local governments are looking to issue bonds to raise money for stimulus spending – which other markets, such as Australia, that are heavily driven by exposure to Chinese demand crave. But they are unlikely to obtain the funds they seek from the Chinese private sector, which still feels under siege as it is required to align with party directions and coalesce with the ailing state sector.

Xi said at calendar new year, acknowledging “headwinds”, that “we will strengthen the momentum of economic recovery”. But how?

Structural reform, including of the unresponsive tax system, remains off the agenda for now. And Beijing has recently restrained discussion and data on the economy, which was an area formerly unusually open to debate.

China may still be growing economically, as Beijing claims, but it is certainly shrinking demographically, the population now declining for two years. The Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences predicts a fall overall from the present 1.4 billion to 525 million by 2100.

Answers elsewhere to the birthrate challenge – immigration, increased workforce participation by women, productivity growth – are not tried, or not working, in China.

This year, hopes rest on the good fortune associated with dragon years to trigger the usual boost in births.

In addition, Xi – whose politburo of 24 comprises only men – has called on women to “carry forward the traditional virtues of the Chinese nation” while also “actively cultivating a new culture of marriage and childbearing … a new trend of family”.

Last year the Jiangsu provincial government attributed its declining population to “the significant increase in women’s educational level”. A post on social media platform Weibo responded: “So, no more foot-binding, but brain-binding now?”

And China’s exposure to the world has contracted steadily under Xi and is now palpably narrower than its East Asian neighbours. It has only about one million foreign-born residents, an eighth of those in Australia.

American author Howard French has written in Foreign Policy following a recent return to China that the absence of foreigners may be “a symptom of something much larger. At stake for the country is whether China’s best bet … is doubling down on a restrictive, security-driven view of the world that constantly elevates self-reliance and control, or recommitting itself to the relative openness of an earlier, more self-confident time.”

Exiled Chinese artist Ai Weiwei anticipates that this Year of the Dragon will be “uneasy, uncertain or dramatic”. It certainly began unpropitiously, with blizzards blocking millions from travelling to family reunions.

Xi will probably avoid, for now, an existential crisis – economic collapse, attempted coup or one he would bring about through an attempted invasion of Taiwan.

Indeed, he is pressing on – with intensified “no limits” support from Putin, Russia becoming China’s chief source of oil – to elevate his personal stature and to bid for Chinese global leadership, as China Media Project director David Bandurski says, “entangling the entire world in the wires of a complex party political discourse”.

Yet at some stage China’s dire economic and social challenges must crash into Xi’s ideological and governance triumphs. That will be some train wreck, a high-speed rail version. Either survivors, or those who chose not to buy tickets, will take over.

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout