None of those features is as enduring as politically motivated assassinations. Their first recorded instance was in 1015, when Boris and Gleb, the younger sons of Prince Vladimir, were killed by their elder brother, Sviatopolk, who wanted an undisputed path to the Kievan throne.

The brothers had been warned; but infused with Christian brotherly love, they refused to fight or flee. Becoming the first two Russians to be canonised by the church, their example defined an ideal of patient suffering in the face of evil that permeated the spiritual life of Russia’s peasantry.

However, Sviatopolk’s example proved influential too. From Peter the Great – who, fearing his unduly devout son Aleksei lacked the ruthlessness to rule, had him tortured and executed – to Catherine II (“the Great”), who organised the assassination of her husband, Peter III, and Alexander I, who was complicit in the assassination of his doting father, Paul I, intra-elite murders figured unusually prominently in the formation of Russian absolutism.

That was, in large part, because of Russian absolutism’s fundamental paradox: it was extremely powerful yet poorly institutionalised.

Thus, the 18th century saw the entrenchment in Western Europe of rules of succession: in England in 1701, the Hapsburg empire in 1713 and Sweden in 1719. But Peter the Great abolished those rules in 1722 and they were never fully reinstated, encouraging murderous rivalries within the ruling elite.

At the same time, the Russian legal system lagged far behind its Western counterparts, so that legality issued solely from the untrammelled will of a transcendent ruler. With little by way of institutions that could mediate between the autocrat and a sprawling empire, all efforts at modernisation had to come from the top. Yet those efforts were invariably curtailed, if not reversed, as soon as they threatened autocracy’s foundations.

The result of political paralysis was to fuel revolutionary movements that, as the imperial succession stabilised, replaced murders from within the elite by a wave of murders from below.

Epitomised by the assassination in 1881 of Alexander II, that wave’s salient features were not just its scale but the terrorists’ idealisation of violence. Violence against “enemies of the people” was not merely necessary: it was redemptive. As the terrorist Sergey Nechayev, who greatly impressed Lenin, put it, “everything that promotes revolution is moral; everything that hinders it is immoral”.

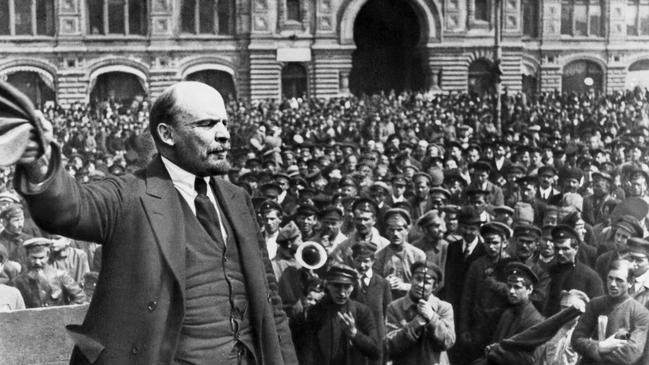

It was in that spirit that Lenin, having decreed that Bolshevik rule would be based “not on law but on unlimited force”, unleashed Russia’s third great wave of assassinations, which this time came from above.

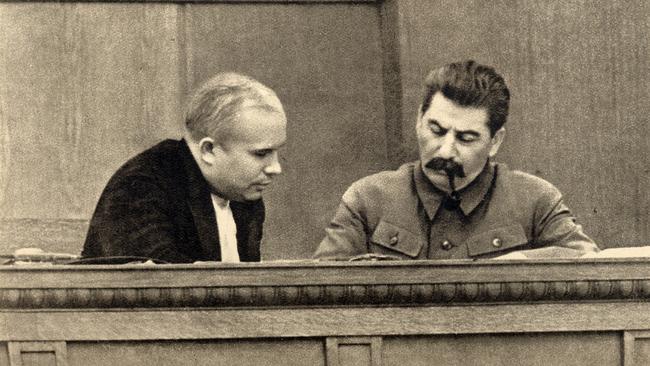

Culminating in the horrors of Stalinism, the third wave’s ferocity was clearly unsustainable. Once the regimes of Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev had rebuilt the institutions Stalin’s purges shattered, their commitment, however insincere, to “socialist legality” moderated the repression. Yet it remained firmly in place – as the shocking prison camp deaths, under Mikhail Gorbachev’s watch, of two great writers, Vasyl Stus and Anatoli Martchenko, grimly showed.

In theory, all that should have ended with the USSR’s collapse, which supposedly inaugurated Russia’s transition to the rule of law. In reality, what distinguished Russia’s 1991 “velvet revolution” was that a purportedly democratic movement gained power through thoroughly undemocratic means.

By 1993, when Boris Yeltsin announced he was “taking anti-democratic measures so as to assure the preservation of democracy”, the new regime’s all-out attack on parliament and the Constitutional Court had crippled both, opening the road to government by presidential decree. To make things worse, as Yeltsin declined into alcoholism and uncontrollable venality, the pillage of state assets and organised criminality that had emerged in the USSR’s closing years got free rein, plunging Russia into chaos and shredding democracy’s legitimacy.

The transition in 1999-2000 to Vladimir Putin was therefore experienced as a relief. Putin promised that Russia’s “path forward (is) the path of democratic development”; but his mission, Yeltsin bluntly said, was to end “the democratic revolution and return to the concept of statehood”. Just as the Thermidorian Reaction in 1794-95 had allowed Napoleon to grasp power for himself and for the new class that emerged from the devastation of the French Revolution, so Putin used his ruthless assault on the Yeltsin era’s chaos to install an autocracy based on corruption, cronyism and fear.

A chilling harbinger of the change came in July 2000, only a few months after Putin had been elected, with the murder of Igor Domnikov, a prominent journalist and anti-corruption campaigner. A new, fourth, wave of political assassinations was clearly getting under way; as it gathered pace, judicial safeguards were gutted, prison sentences for political offenders ratcheted up to two or more times those that prevailed in the Brezhnev years and prison conditions dramatically harshened, jeopardising political prisoners’ lives.

Initially, an economic recovery boosted the regime’s popularity; but as it petered out, Putin – having none of Napoleon’s virtues and all of his imperialistic vices – relied ever more heavily on the appeal of aggressive revanchism. With Russia managing to dismember Georgia, seize Crimea and occupy large parts of Donbas, Putin’s image as a conqueror gained growing resonance in the polls. Moreover, each foreign adventure gave the regime an excuse to demonise its opponents as Western agents, bolster the security services and further suppress civil society.

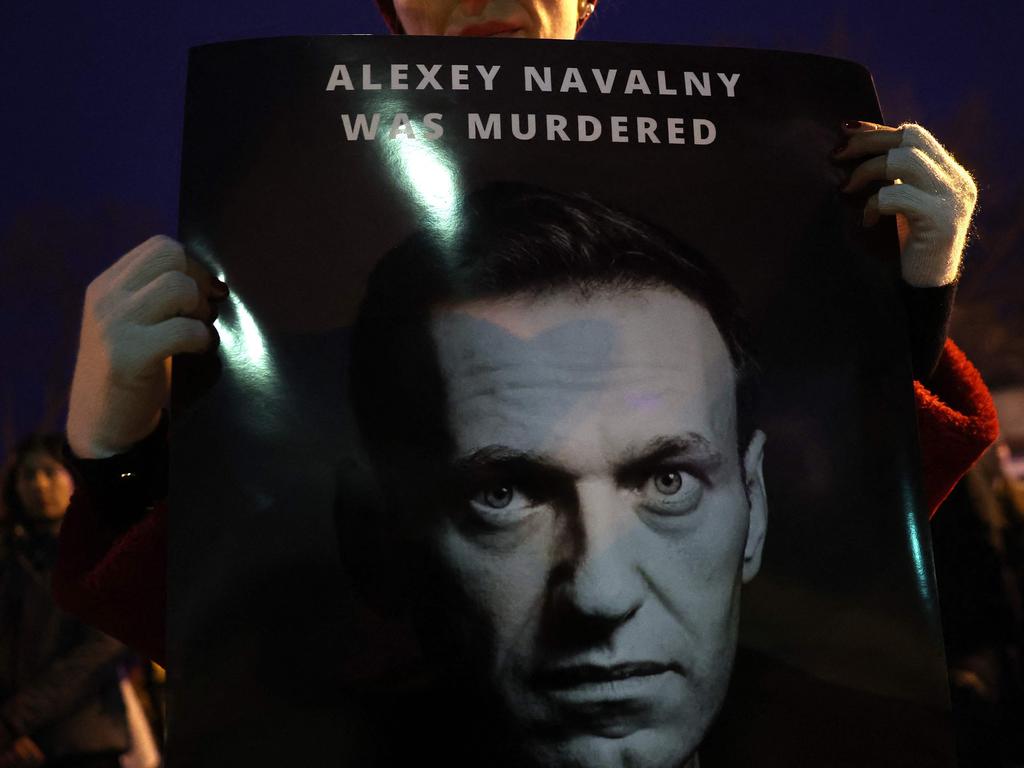

Yet the most sinister feature of the fourth wave was not its intensity: Russia had seen far worse. Rather, it was that while every previous regime had tried to hide deadly violence, Putin shrugged it off or even flaunted it as a badge of honour.

Appealing not to the West but to the thugs who dominate the Third World, Russia’s soft power was now defined by unabashed savagery, rather than by pretended civility. The mask of hypocrisy could be thrown aside; this was the world not of cringing sentimentalism, but of unforgiving, unrelenting Hobbesian battle.

It may be that “assassination never changed the history of the world”, as Benjamin Disraeli said on Abraham Lincoln’s death. Yet it seems more likely that Russia would be a different place if Pyotr Stolypin, the reforming prime minister, had not been assassinated in 1911, or if Fanny Kaplan’s attempt on Lenin’s life in August 1918 had succeeded.

Those are things we shall never know. What we do know is that Alexei Navalny and countless others are dead, murdered by a regime that believes only in brute force. On this second anniversary of its invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s comprehensive military defeat remains the best way of showing that regime, and its authoritarian friends, that aggression doesn’t pay – and of ensuring its innocent victims did not die in vain.

Like a distorting mirror that twists image out of shape, Vladimir Putin’s regime is an increasingly grotesque reflection of Russia’s past. Now, the death of Alexei Navalny has highlighted the regime’s reversion to that past’s worst features.