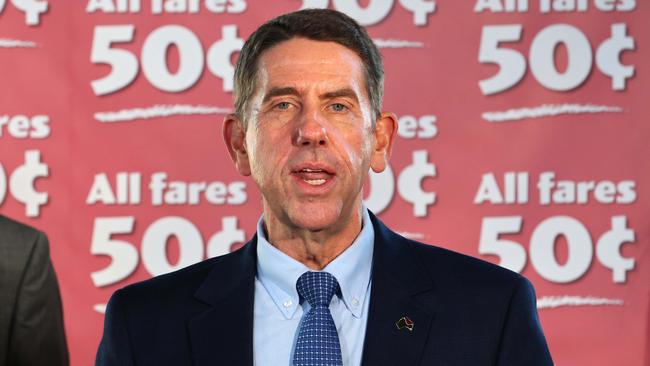

Queensland Premier Steven Miles banks on budget to save his Labor government

Tuesday’s budget will plunge Queensland into a $3bn deficit as Labor embarks on a monster spending spree in a last-ditch effort to recapture voters.

It is the spending spree Steven Miles is banking on to save his government.

A year after a super-profits tax on coal companies handed Queensland’s Labor government the largest surplus in history, the budget to be handed down on Tuesday will plunge the state into a $3bn deficit and push public debt to record levels.

However, the government is prepared to wear the costs. It seems the only motivation is to dole out a monster cost-of-living package to recapture voters who, according to successive polls, are abandoning it in droves.

The threat to the long-term government’s hold on power was exposed in March when it suffered a thumping by-election defeat in its heartland electorate of Ipswich West and a 21 per cent swing against it in Annastacia Palaszczuk’s former seat of Inala.

Despite persistent inflation, Miles has promised the budget will give more handouts than any other state government budget has in Australian history. But will the flurry of giveaways be enough to rescue Miles and deliver Labor a miracle election win?

Labor swept to power in 2015 under Palaszczuk and managed to increase its seat count at two successive elections, in 2017 and 2020.

Facing crises on numerous fronts and on the nose with voters, Palaszczuk caved to factional pressure and quit as premier in December. ALP strategists were relying on a bounce in the polls after Miles was installed as leader, but the party’s primary vote has continued to tank.

With senior party figures bracing for an election wipe-out – Miles conceded in April it was “very likely” he would be ousted as Premier – the focus has turned to saving the furniture. Tuesday’s budget will be a last-ditch effort to mitigate losses and hold on to government.

The Premier and his Treasurer, Cameron Dick, have no qualms about emptying the piggy bank to try to restore the government’s standing with a hostile electorate.

A Labor victory is improbable, with disillusioned voters under enormous cost-of-living pressure and the state suffering a spiralling rental crisis, surging crime and public hospitals at breaking point. But it is not impossible.

A recent uComms poll of 2400 voters indicated support for the third-term Labor government had lifted on the back of a pledge to give every household a $1000 energy rebate. Commissioned by Together Union, the poll showed Labor’s primary vote went from 26.9 per cent in April to 30 per cent on May 14 – the night of the federal budget – with Liberal National Party support falling from 35.1 per cent to 33.7 per cent.

The poll suggests a tighter election race than was widely anticipated and voters were surveyed before the government’s announcement of a six-month trial to slash public transport fares to a flat 50c fee across the state and more yet-to-be-announced sweeteners in Tuesday’s budget.

It could be an aberration. Another poll done by RedBridge Group in two waves in February and May shows Labor’s primary vote collapsing to 28 per cent, just above the 26.7 per cent recorded at the 2012 election when the party was reduced to a rump of only seven MPs.

The big-spending pre-election budget strategy was pioneered by Liberal prime minister Malcolm Fraser with his 1977 “fistful of dollars” campaign and perfected by John Howard in the 2000s, and there is no doubt Miles and Dick will use Tuesday’s budget to lay the basis for the state election in October.

The pair are building a political narrative around the budget, aimed at boxing in the LNP on whether they will match the government’s big-spending agenda or resort to cutting jobs and services.

It is a classic Labor wedge, designed to force LNP leader David Crisafulli to cough up cash or be seen as the bad guy in a cost-of-living crisis.

Trying to wriggle out of the squeeze, Crisafulli made an extraordinary pledge this week to honour all commitments made across the four-year forward estimates in next week’s Queensland budget, including all infrastructure projects and funding to social services.

Crisafulli’s small-target strategy has underpinned the growing momentum of the LNP across the past three years, hammering the government on youth crime, soaring cost of living and ambulance ramping. Although the election is four months away, the LNP also is under intensifying pressure to explain its plans to manage debt.

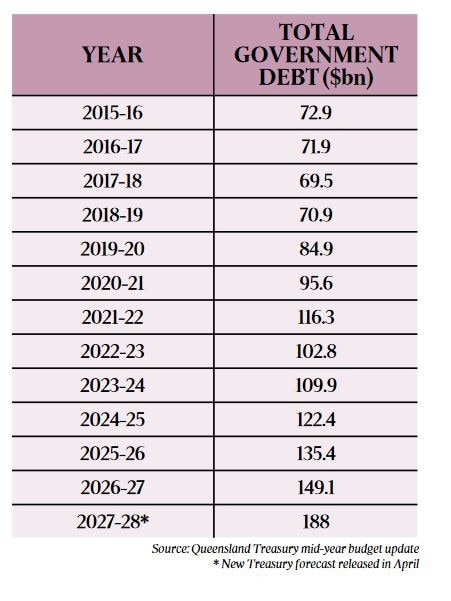

The projection that gross debt levels will surge to $188bn in the next four years – $41bn more than forecast in last year’s budget – should demand spending discipline but has been overshadowed by mounting pressure to spend more on housing, health and tackling crime.

On the government’s preferred measure of net debt, which excludes debt carried by state-owned companies, borrowings will skyrocket from $5.85bn last year to $73bn by mid-2028.

Unlike the 2015 election, which was dominated by debate over debt levels, both Labor and the LNP have largely avoided the issue and failed to detail any debt-reduction plans.

Crisafulli promised a debt reduction strategy 19 months ago but has refused to release it until closer to the election. He says taxes and debt would be lower under an LNP government but will not articulate how he plans to achieve that.

Dick has abandoned any pretence of containing debt, with no ambition to regain Queensland’s AAA credit rating – downgraded in 2009 in the wake of the global financial crisis.

“Our position is clear, the focus of what we have to do is to support Queenslanders in a time of need,” he has told Inquirer. “We are in a very strong position compared to our competitor states, NSW and Victoria.”

Net debt levels are lower in Queensland, partly because it is the only state with a fully funded superannuation scheme for its public servants.

The collapse of the state banks in South Australia and Victoria – which brought down two Labor governments in the early 1990s – were galvanising for state administrations.

Keith De Lacy, hailed as one of Queensland’s best treasurers, was a hardliner on debt and ruled over the finances of Wayne Goss’s Labor government with an iron fist.

Inheriting a legacy of shrewd financial management from the Bjelke-Petersen era, De Lacy kept borrowings under control in the 1990s while the Goss government embarked on a reform agenda.

But debt levels began to soar in the final few years of the Beattie Labor government, and then through the Bligh Labor government as it moved to meet infrastructure shortfalls and pay for services in the face of falling revenues.

There were efforts to reduce debt during the one-term LNP Newman government and in the early years of the Palaszczuk government, but mammoth debt growth was normalised across the country with the onset of the Covid pandemic to save jobs and keep the economy afloat.

Joe Branigan, director of Tulipwood Economists, has warned that the reluctance of both major parties to put debt at the centre of economic policy is negligent.

He says dramatically rising debt matters for four reasons.

“First, balancing budgets means governments are being fair across generations and not asking the future to pay for the present,” he says. “Second, meeting a hard fiscal constraint forces governments to prioritise spending, which improves the quality of spending.

“Third, as global interest rates have returned to neutral levels, the cost of borrowing in terms of interest repayments matters greatly again.”

Branigan’s final reason debt reduction must be prioritised is that the rate at which the government has been borrowing fails to reflect the risk of the infrastructure project or the quality of the expenditure.

“Rather, projects and policies must be assessed on their merits in meeting clearly defined public policy objectives, not because governments perceive debt to be cheap.”

There is also a host of expensive infrastructure projects that are yet to have capital expenditure laid out in the budget. The Pioneer-Burdekin mega-pumped hydro project – tipped to cost more than $12bn – has been allocated only $1bn so far. Then there is a new desalination plant – estimated to cost between $4bn and $8bn – that has yet to make its way into the budget papers.

A big-spending infrastructure program and other concessions including 50c public transport fees and the energy rebate for households – on top of a $300 subsidy from the federal government – run the risk of adding to inflationary pressures.

Dick insists his budget will put “downward pressure on inflation” by mechanically driving down the consumer price index, but economist Saul Eslake says there is always risk when governments throw money at households when inflation is higher than it should be.

“It doesn’t mean that rates are going to go up because of what state governments are doing, but it could mean that rates take longer to start coming down,” he says.

“The Reserve Bank is looking at what state governments are doing.”

And with an election around the corner, voters will also be keeping close watch.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout