After dragging the travelling media around Beijing’s Temple of Heaven in an unseasonable cold snap to pay tribute to Gough Whitlam’s visit 50 years earlier, the Prime Minister was asked whether he trusted Xi Jinping. He stammered about “positive and respectful” relations, and later about dealing with the Chinese dictator at “face value”. Really?

The answer was clearly “no”, but Albanese – a career politician with 27 years’ experience – struggled to come up with a form of words to say so in a sufficiently nuanced way.

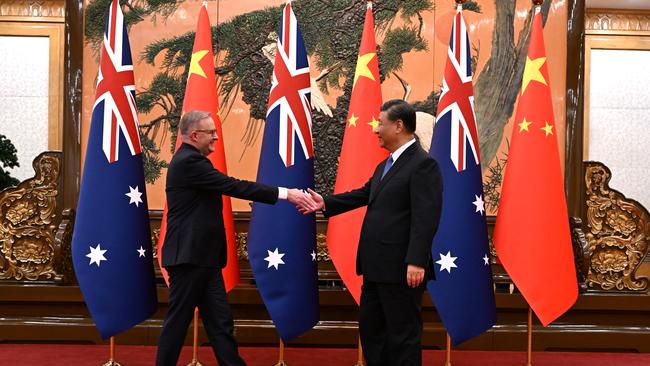

His coyness, on Xi’s home turf, came just five hours before his long-awaited meeting with the Chinese supreme leader.

A day earlier Albanese was asked several times whether China should be allowed to join the free trade bloc known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

This should have been an even simpler question as he had solid policy backing to tell it straight. Australia is opposed to China joining the pact.

But Chinese Premier Li Qiang had declared not long earlier that the communist giant would “actively promote” its CPTPP membership bid and claimed it would uphold international trading rules.

So Albanese blathered instead about CPTPP membership requiring unanimous support and pointed to the long line of aspirants seeking to join the deal.

You’d think he’d be more upfront, considering China’s three-year campaign of economic coercion against Australian exporters.

The truth is China will never qualify for CPTPP membership as the rules stand.

The trade deal has the highest standards of any multilateral free trade agreement, requiring transparency in public administration, legal protection of intellectual property rights, a level playing field for foreign financial institutions, and for state-owned enterprises to be run in a non-discriminatory manner. China is an opaque communist dictatorship where the only reliable rule of law is the party is always right.

Senior government figures briefed journalists afterwards that Australia’s position had not changed.

Failing to say so places the full burden of China’s disappointment on others – chiefly Japan – to set things straight. Australia’s quasi ally and Quad partner was already on edge about Labor’s improving China ties.

So it’s unsurprising the Prime Minister dropped Penny Wong in Tokyo to reassure her counterpart, Kamikawa Yoko, as Albanese headed from Beijing to the Cook Islands for the Pacific Islands Forum.

His Foreign Minister would have had some explaining to do.

Eyebrows also will have been raised in Washington, where the Biden administration is on alert for signs Australia might get the wobbles. And spare a thought for Pacific Island leaders who’ve been lectured for years by Australia about the dangers of doing business with China.

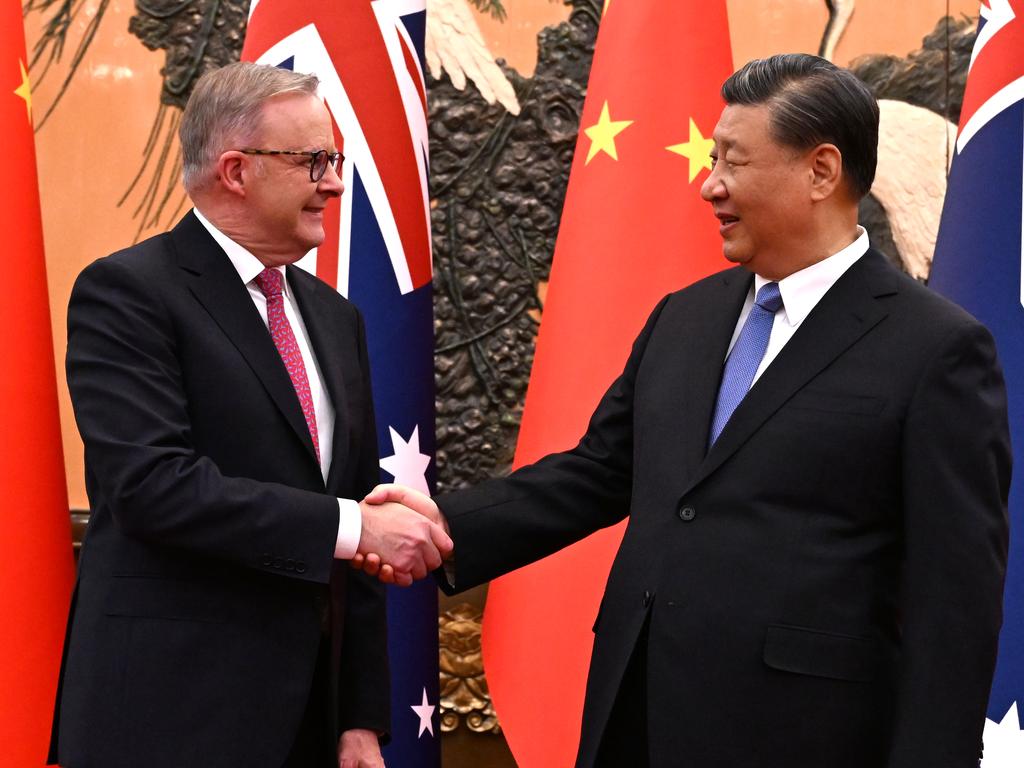

Albanese’s “co-operate where we can, disagree where we must” formula did the job in getting Australia back to the table with China to stabilise the countries’ relations, which had become shrill and unproductive.

In this sense, Albanese left China with a win, and a well-timed one considering the fallout from the voice defeat and the cost-of-living crisis sucking support from the government.

It was a success achieved without significant compromise by Australia, beyond relinquishing its position as an unrestrained China critic.

But where to from here?

The trip restored annual talks between the Prime Minister and Premier Li, and a range of other ministerial and official-level dialogues.

These will support a more positive bilateral relationship, for the time being at least.

But beyond selling it iron ore, coal and gas for mountains of cash, co-operating with China is inherently risky. Disagreeing too quietly is also problematic, as it lets down partners and emboldens Beijing to continue its bad behaviour.

The real problem for the government is it is walking a diplomatic tightrope without any real safety net as the world is becoming increasingly dangerous. Australia’s Defence procurement is a mess, despite its $52bn annual budget.

It will be years before Australia gets promised new surface ships and missiles, and decades before Australia has a working nuclear-powered submarine capability, if it ever does.

Meanwhile, China continues to pump out ships and submarines at an astonishing rate and, according to the US military, has set a 2027 deadline to be ready to take Taiwan by force.

Beijing is also waging “the most sustained, sophisticated and scaled theft of intellectual property and expertise in human history”, ASIO chief Mike Burgess warned just weeks ahead of the trip.

And Australia and the US will continue to play whack-a-mole with China in the Pacific as Beijing buys the favour of regional elites in the hope of securing a strategic foothold.

Australia’s relations with China may be more civil than they were, but the nation’s security remains as precarious as ever.

Try as he might to avoid pesky questions, there were some awkward ones for Anthony Albanese in China this week.