Australia out of the seven-year China deep freeze

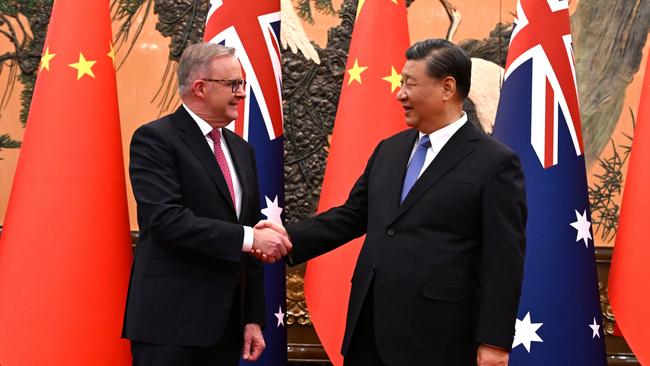

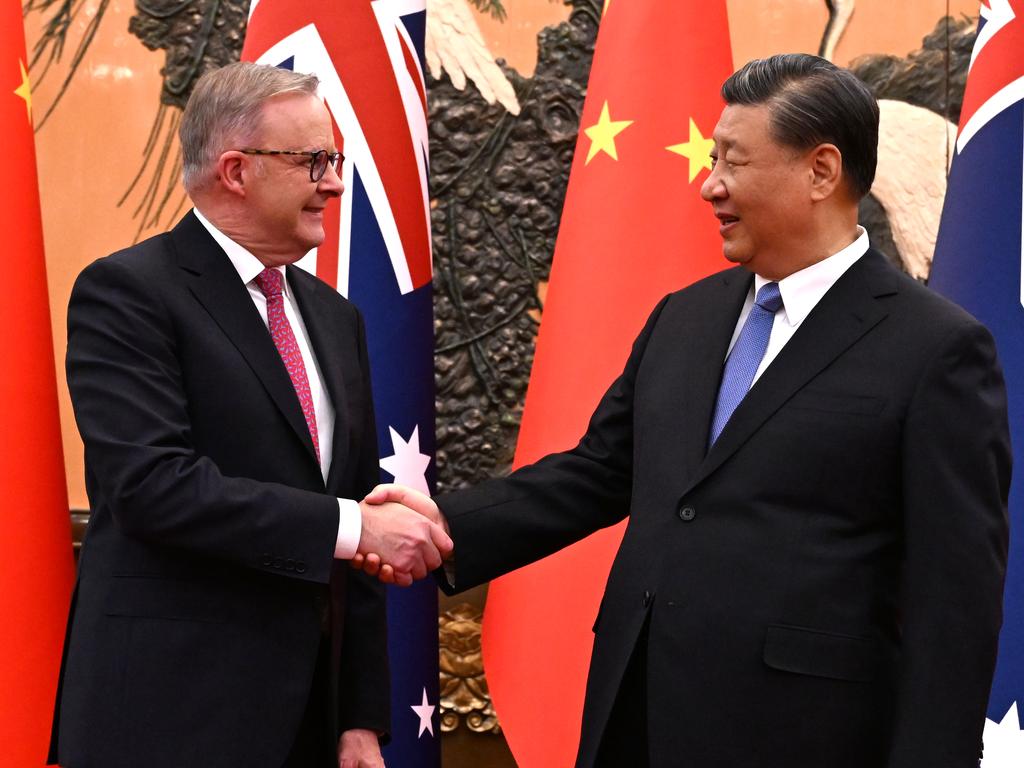

After a seven-year freeze, Xi Jinping finally allowed an Australian Prime Minister to enter the ominously proportioned Great Hall of the People for a chat.

After a seven-year freeze, Xi Jinping finally allowed an Australian Prime Minister to enter the ominously proportioned Great Hall of the People for a chat.

All that was required to secure Monday night’s meeting was for the Australian people to change their government to one Xi’s China would agree to deal with and for Canberra to conduct 18 months of exhausting diplomatic negotiations.

Beijing decided, in the view of senior Australian diplomats, to wait out the Morrison government in 2020, saying the Coalition was “entirely to blame” for the bilateral breakdown.

Anthony Albanese has been the beneficiary of that.

Late on Monday, the Prime Minister was rewarded with an audience with the most powerful Chinese communist leader since Mao Zedong.

“I’m convinced that we’re building a relationship that’s a constructive one, where we’re able to talk with each other directly,” Albanese said hours before the meeting.

Both Canberra and Beijing cast this leaders’ meeting as historic. To set the scene, Albanese earlier on Monday embarked on a Gough Whitlam pilgrimage.

Xi must have smiled when he was briefed about it. The Prime Minister’s recreation of Whitlam’s outing to the imperial Temple of Heaven is exactly the sort of symbolism his propaganda machine relishes.

Ever since the Albanese government came to power last year, Beijing has called for Canberra to embrace the “spirit of Whitlam”.

China’s top envoy in Australia, Xiao Qian, was still doing it hours before Monday’s meeting. Xiao even accompanied the Prime Minister and Penny Wong as they traced the steps of the Labor giant.

“Can I make a suggestion?” Xiao volunteered at one point. “This is where Gough Whitlam had his photo taken.”

Minutes later, so had Albanese.

It is understandable the Prime Minister went along with the act. Whitlam has a mythical status among the Labor Party, especially among the Left faction that Albanese comes from.

And Whitlam’s 1973 trip truly was historic – at least for Australia. It was the first visit by an Australian leader to the People’s Republic of China.

“The Labor Party cares about our history. And Australia cares about our history too,” Albanese said.

On that trip 50 years ago, Whitlam met Mao less than three years before the dictator’s death. The chairman mumbled, rather than spoke. He was well on his way to senility.

Albanese instead encountered a Communist Party general secretary at the peak of his powers.

China’s economy may be encountering troubles and many of its neighbours may be working together to try to constrain its growing military might, but the 70-year-old Xi completely dominates the Chinese political system.

His word makes Chinese foreign policy, and that makes time with him crucial to any country trying to have something approaching a normal relationship with his China.

Thankfully, Albanese oversees an Australian system far more united in its China policy than Whitlam’s was.

Back in 1973, many of Australia’s best and brightest diplomats found it difficult to “accept the Whitlam idea of China”. Many of its top Asia experts thought the Whitlam government’s “‘no threat thesis on China” was worryingly misguided.

There is no such gulf in this Australian government, despite the grumblings of a clutch of retired diplomats. The view of China as a benign force in the region passed long ago. Xi himself has been responsible for changing the minds of many.

Canberra has used this meeting as leverage. In the lead-up to the audience with Xi, there has been trickle of good news as most of China’s trade sanctions have been unwound. The $700m live lobsters trade is expected to resume soon after the visit, another reward by China’s leader.

Cheng Lei, thank heavens, has finally been let out of prison.

But future good news is hard to see. The structural problems that weight on the relationship are profound: threats of war issued to Taiwan, high-risk manoeuvres by the People’s Liberation Army in the South China Sea and the near total opacity of the policymaking process in Xi’s Beijing.

Yang Hengjun remains in a prison cell, not far from the Great Hall of the People.

Our two countries still don’t trust each other. It will take a lot more than a 60-minute discussion with China’s control-obsessed leader to fix that.

Journalists travelling with Whitlam on that 1973 trip reported the prime minister was in a “triumphant mood” after his brief meeting with the aged Mao.

“Spirited renditions of Waltzing Matilda, Advance Australia Fair, and old Labor songs floated into the dark Peking night as politicians and officials relaxed in the Chinese capital,” according to a contemporaneous report in The Sydney Morning Herald.

After his Monday night meeting, Albanese met travelling journalists at the residence of Australia’s departing ambassador in China, Graham Fletcher.

Mercifully, not a single Labor song was sung. For all the day’s pageantry: Whitlam’s China euphoria remains a relic of a distant past.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout