Swinging voters, baseball bats: The humbling lesson David Crisafulli will never forget

The making of David Crisafulli was his crash to earth as a cocky first-term state MP and minister who seemed destined to rise high in Queensland politics.

The making of David Crisafulli was his crash to earth as a cocky first-term state MP and minister who seemed destined to rise high in Queensland politics. The hardest swinging voters in the nation pulled out the baseball bats and taught him a lesson he would never forget.

Nearly a decade on from that humbling denouement – he was swatted from parliament, a victim of the electoral backlash that put paid to combative Campbell Newman’s strongly positioned government and restored Labor to power after only a single term in opposition – Crisafulli is poised to make amends and possibly some history of his own at the October 26 state election.

The 45-year-old Liberal National Party leader enters the campaign proper next week as white-hot favourite to become Queensland’s 41st premier. Newspoll shows it is his fight to lose against Steven Miles, who succeeded three-time election winner Annastacia Palaszczuk barely 10 months ago and has struggled to get his arms around the poisoned chalice he inherited.

Crisafulli’s watchwords are work, discipline, caution and more work. He presents as a man willing to take nothing for granted, to leave as little to chance as possible in the frenetic sprint to polling day.

Had the voters had their say last week, he would have been the comfortable winner: The Weekend Australian’s Newspoll puts the LNP 10 points clear of Labor after preferences and there is daylight between the leaders’ personal numbers. Crisafulli leads 46-39 per cent on the key measure of preferred premier that traditionally favours the incumbent, reinforcing perceptions a change of government is imminent.

Fellow Queenslander Peter Dutton will certainly hope so. While it is unwise to extrapolate a state outcome to the national level, victory for the LNP would be a fillip for the blue team in the countdown to the federal election Anthony Albanese will call by next May. Atmospherics are always important in politics, and the Country Liberal Party’s triumph in the Northern Territory last month breached the red wall of mainland Labor governments.

A result for the LNP on Dutton’s home turf would boost Coalition morale and fundraising prospects coast to coast. If Miles contrived, however, to pull off the Houdini-like act of delivering Labor a fourth consecutive state term, the Liberal-Nationals merger would come under renewed if not irresistible pressure.

The LNP is cumbersome to operate in Canberra. It was created to govern in Queensland, and if it can’t knock over Miles’s tired and unpopular outfit, what’s the point of it?

No pressure then, DC, to borrow the nickname Crisafulli’s advisers use. No pressure at all.

When we sit down to a working lunch at one of Crisafulli’s favourite haunts, Paradise Point Bowls Club, on the northern lip of his Gold Coast seat of Broadwater, he expresses the hope we’re hungry because he certainly is.

As usual, he has been up before the sun to hit the gym. He has done a media doorstop where he banged on about the LNP’s “adult crime, adult time” antidote to youth offending – a problem that has galvanised the electorate, especially in north Queensland where he grew up on a sugarcane farm outside smalltown Ingham. Crisafulli likes to say his values come from there.

He orders a steak – rare, please – with mashed potato and greens, washed down by mineral water for the table. The eatery staff know him, all right. His plate arrives piled high and he goes at it with gusto. Chomp, chomp.

We’re talking about the man he was and who he became after that chastening election defeat in 2015. Until then, Crisafulli’s future looked assured. Following high school, he had studied journalism at Townsville’s James Cook University and landed a job as a cadet reporter on his local paper, the Herbert River Express. He wound up on regional TV.

But his dad, Tony, let the cat out of the bag recently by recalling that young DC always had his sights set on politics. “That’s his way of saying he didn’t think I was a good farmer,” Crisafulli quipped, unconvincingly, during their awkward exchange for a profile segment on Nine News.

Tony: “No, no … he just wanted his thing for politics … it’s in your genes if you want to do something.”

Soon enough, 23-year-old DC was working as a staff member for Townsville-based Liberal senator Ian Macdonald in 2003. Within a year he ran for an elected spot on Townsville City Council, considered at the time to be a closed shop for Labor. He wore out three pairs of shoes doorknocking and won; he stood for the deputy mayor’s job in 2008 and got that to boot. By then he had married his teenage sweetheart, Tegan, the mother of their two daughters.

Anna Bligh’s state Labor government was on its last legs when Crisafulli was preselected by the LNP to contest the local seat of Mundingburra at the 2012 election. Newman, parachuted into the leadership from outside parliament, chalked up a win for the ages, capturing 78 of the 89 seats in state parliament then on offer. He went straight into cabinet as minister for local government, characteristically impatient to make his mark.

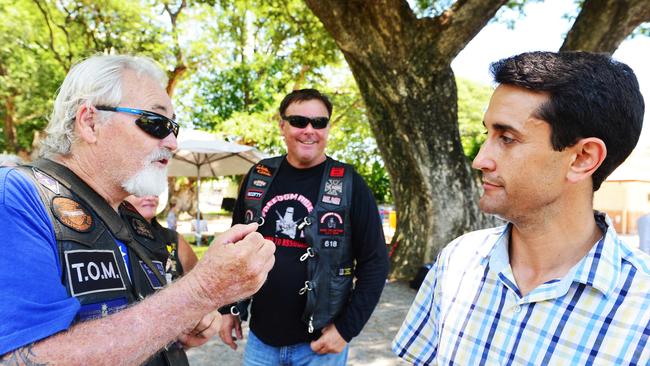

Unfortunately for him, what should have been a two or three-term government turned out to be a lone-term disaster for the LNP. The headstrong Newman brawled with all comers – public servants on job cuts, the judges over a crackdown on outlaw motorcycle gangs – and further alienated a sceptical electorate when he tried to rebrand as 99-year leases the state asset sales on which he had savaged Bligh to pay down surging public debt.

The tide went out as swiftly as it had come in, leaving Crisafulli high and dry, out of parliament, out of a job, and Palaszczuk unexpectedly premier in a minority Labor government. (Newman also lost his suburban Brisbane seat.)

Father-of-two Crisafulli moved the family to the Gold Coast and went into business as sole director of a training company, SET Solutions, that failed in 2016 owing creditors more than $3m. Following allegations that the firm might have traded insolvent, Crisafulli paid $200,000 to settle claims from liquidators; he denies any wrongdoing.

In 2017 he seized his opportunity to return to state parliament via blue-ribbon Broadwater, ousting incumbent Verity Barton, one of the LNP’s under-represented female MPs, in a bruising preselection challenge. It’s hard to see how he would get away with that today. Labor accused him of “destroying the career of the youngest woman in parliament”, while Barton’s supporters claimed the branch had been stacked, an accusation Crisafulli rejected.

Speaking publicly of those events for the first time from Britain, where she has built a career as a corporate consultant, Barton is magnanimous. “David is a determined man with a clear sense of the Queensland he wants to create,” she says.

Even now, the memory of those fraught times still animates the LNP leader. Crisafulli stabs at his beef. He admits that he pushed too hard and being belted by the voters in 2015 was the life lesson he needed. “You can make reform, but you can do it with compassion,” he says, recounting what he took out of that “humbling” experience.

“You can make the decisions that are needed, but you can still treat people with respect and decency. I genuinely believe I have always been a good listener and … the longer I’m in public life, the more I see the value of compassion and empathy and … I think that’s one of the really important things that I’d like to see if we were to win the election.”

Sounds reassuring, and those who know the man attest that he absorbed the mistakes of the Newman government and is the better for it, both as a person and politician.

Up to a point. Like Can-do Campbell, Crisafulli is renowned for his absolutist tendencies. The term control freak crops up frequently in discussion about him with past or present colleagues.

Newman doesn’t buy it. He tells Inquirer: “I found him to be highly energetic, very intelligent, quick on the uptake … He was indeed very ‘can-do’, can I say, and just very action oriented. I know the guy I had in the cabinet and he’s not the guy we’ve seen in the past few years.

“I’m very confident that guy is there, but he’s been hiding his light under the bushel in the proverbial way, as he sort of traversed that journey as Leader of the Opposition.”

Another class of 2012 alumnus, Sam Cox, who came a cropper in the seat of Thuringowa adjoining Crisafulli’s then Townsville electorate and later defected to One Nation, says: “Anyone who knows David knows he has worked all his life for this … he’s planned to be in this moment.” While they remain friends, Cox says they no longer discuss politics.

Crisafulli could probably live without this kind of commentary – especially from his former boss. Newman also quit the LNP in 2021, citing his dismay at Scott Morrison’s “heavy-handed” Covid response and a failure by Coalition governments at the state level to stand up for core liberal values, going on to run unsuccessfully for a Senate seat with the Liberal Democrats. Labor is hoping the shadow of the 38th premier continues to loom large in Queensland, and depicts Crisafulli as a Campbell clone who seeks to skate into office on a “small target” strategy. Once there, he would revert to type and scorch the earth.

Crisafulli sighs, passing his mobile phone across the lunch table. He has clicked on a photo sent by a relative in Townsville, a key state election battleground where his old stamping ground of Mundingburra is one of three ALP seats up for grabs. It shows a Labor billboard, adjacent to a LNP hoarding featuring Crisafulli’s image, claiming he would revive privatisation of Queensland’s state-owned power assets and ports if given the opportunity. How many times did he have to rule this out, he asks. “Queensland spoke on that.”

As we report in the news section, Crisafulli is doggedly determined not to be dragged off message by Labor or the media. Disciplined to a fault – that term again – he continues to hammer a select number of themes: youth crime, healthcare, cost of living and housing affordability. Governing at the state level is about service delivery, and the LNP, he says, lost sight of that truism.

“Part of the reason why the Labor Party has governed almost exclusively in Queensland for the last three decades is because we, as a political movement, haven’t been focused on service delivery,” he says.

Was his side too fixated on the value issues driven by its powerful Christian right wing? Distracted by Newmanesque symbolism such as making convicted outlaw bikies wear pink prison garb or some other outbreak of culture warfare?

Crisafulli responds cautiously. “That would be wrong to say that … but let me give you an example. When I became leader some people said to me: ‘Focusing on the health system is not something that is an equity of the LNP.’

“I disagree. I’ve seen the complete and utter disintegration of health services in this state – everything from escalation of ambulance ramping, to waiting lists and the closure of services in regional areas. Now, in the past, we haven’t had a laser-like focus on fixing the health system. And the fact that Queenslanders are looking at us as a solution to the health crisis, I think, shows the results of four years of discipline, not just for me … that’s been a combined effort.”

Certainly, his me-tooism in backing Labor policy has dismayed conservative purists.

Crisafulli in June made an unprecedented commitment to adopt Miles’s big-spending budget, vowing to honour all infrastructure projects and social services funded across the forward estimates. He voted his conscience against Palaszczuk’s abortion and voluntary euthanasia law reforms but insists the questions are settled and won’t be revisited by an LNP government.

There will be no rerun of the proposed 14,000-strong public service cull that arguably doomed Newman’s government at the outset, even though the LNP is critical of the extra 57,000 hirings made under Labor, excluding police, doctors, nurses and emergency personnel. (Crisafulli is on another unity ticket with Miles in saying he wants more of these “frontline” workers.)

He insists that state debt, projected to hit an eye-watering $172bn by 2028, will be lower, but doesn’t say by how much, and there’s a commensurate absence of detail around his pledge to ease the state tax burden.

Voters must wait for the campaign to be told of the LNP’s target to reduce ambulance ramping outside choked hospital emergency departments.

He angered federal LNP colleagues when he voted to support state Labor’s emission reduction targets this year and ruled out changing Queensland law to accommodate Dutton’s nuclear energy ambitions, absent bipartisan agreement on the plan.

On the economy, he would bring back the state productivity commission and “provide certainty” around taxation and regulation. Hardly big-bang stuff. Infrastructure projects, including those planned for the 2032 Brisbane Olympics, are to be delivered on time and on budget. The militant CFMEU will be “parked in their box” – though not at the expense of the provocative bragging rights the construction unions’ superannuation fund, Cbus, purchased when it slapped its logo crowning the executive building commissioned by Newman at 1 William St, opposite state parliament.

The LNP faithful hate what the brightly lit sign represents – Labor and its industrial base’s generation of dominance at the top end of town – but Crisafulli will live with it. Although the state pays rent of $74.5m annually on the 45-storey “tower of power”, conferring naming rights to the anchor tenant under normal commercial practice, he accepts the deal was done before his time and Cbus ultimately calls the shots as the building’s joint owner with property fund manager ISPT. “My priority is on the things I am campaigning on,” he says.

As an election game plan, small target is entirely understandable. Like the saying goes, never interrupt your opponents when they’re making mistakes. And Crisafulli knows that every promise he makes on the hustings is a promise he will have to keep in government, limiting his options.

In this regard, his wariness is a measure of the LNP’s confidence that the election is in the bag, however much he protests otherwise. He won’t be stampeded into costly commitments to win votes the party doesn’t need.

An ever-contrarian Newman demurs. “I don’t agree with his small-target strategy,” he says, voicing disquiet that is shared privately by some in the LNP partyroom and organisation. “I feel that people are thirsting for a very clear vision, they want definitive statements on what an incoming government will do.”

Cox notes: “David is all about tactics, about playing the politics … and I just think that’s an indication that he hasn’t got across what he really wants the state to be.”

Credit where credit is due. Managing the clashing interests, egos and churning ambitions that pulse through the LNP is never easy, and as a bridge for the city-country divide the model has its flaws. (Just ask the federal parliamentarians who sit in separate Coalition partyrooms in Canberra.)

Still, it’s fair to say it has never been as united as it is under Crisafulli. True, he’s more respected than liked by the colleagues and tends to keep a personal distance – “it’s all business with him”, remarks one – but there is genuine admiration for what he has done to put the LNP in a winning position come October 26.

The uproar over an abortive coup against LNP leader Deb Frecklington – backed by senior figures in the party machine but, according to Crisafulli, without his knowledge of the plot in his favour – ahead of the 2020 state election at which Palaszczuk increased Labor’s majority has well and truly blown over. Frecklington is an engaged and avowedly loyal frontbencher, alongside two other former LNP leaders in Tim Nicholls and John-Paul Langbroek.

“I’ve been involved with the party since the 1990s and I have never seen a more disciplined, inclusive leader,” says retiring MP Lachlan Millar, who has known Crisafulli since his days as a journalist and is one of the few prepared to speak on the record about him.

Diligent DC is ready, of course, for our questions about his headstart in Newspoll, broadly reflective of other published pre-election data. He says, straight-faced, he’s the underdog. The LNP needs to “climb a mountain” to win the 12 additional seats for a majority in the 93-place parliament and Labor is busily debranding candidates – pulling the party logo off their campaign material – to soft-pedal the modest legacy of its nine years in office, according to Crisafulli.

As he points out, the roster of general election results in post-Fitzgerald Queensland weighs heavily against his side: just that one, tantalising win out of 12 outings since 1986, before the Moonlight State of vice was exposed under Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

If nothing else, Miles has arrested the plunge in the post-2020 state Labor vote Palaszczuk had presided over before she reluctantly accepted her time was up. A historic fourth term for their government is improbable but not impossible, and those irascible Queensland electors do have a habit of defying prediction, as Scott Morrison demonstrated in 2019 when they held the line for the federal Coalition and sealed his “miracle” victory.

Yet the numbers don’t lie, and they’re stacked against the Queensland ALP whichever way you cut it. The LNP attracted an 8.2 per cent swing in Newspoll, notionally yielding 20 extra seats on the 35 it holds if applied uniformly. That’s broadly in line with the breakthrough win for Labor in 1989 by Wayne Goss, the man who coined the aphorism about angry voters and baseball bats, to lay the platform for all those years of state supremacy.

Crisafulli would take that in a heartbeat.

He heaps mash on the last of his steak, pours gravy over the steaming mound, and digs into the paradox of political expectation.

“The problem is when people believe that the government will just change, then there is a real risk that it just won’t,” he says.

“You’ll have people who vote for either a minor party or a local MP and they’ll wake up with a fourth term of this government. And that remains a real risk, and I genuinely believe we remain the underdog … for a combination of that, the quantum of the seats that we need to win and history.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout