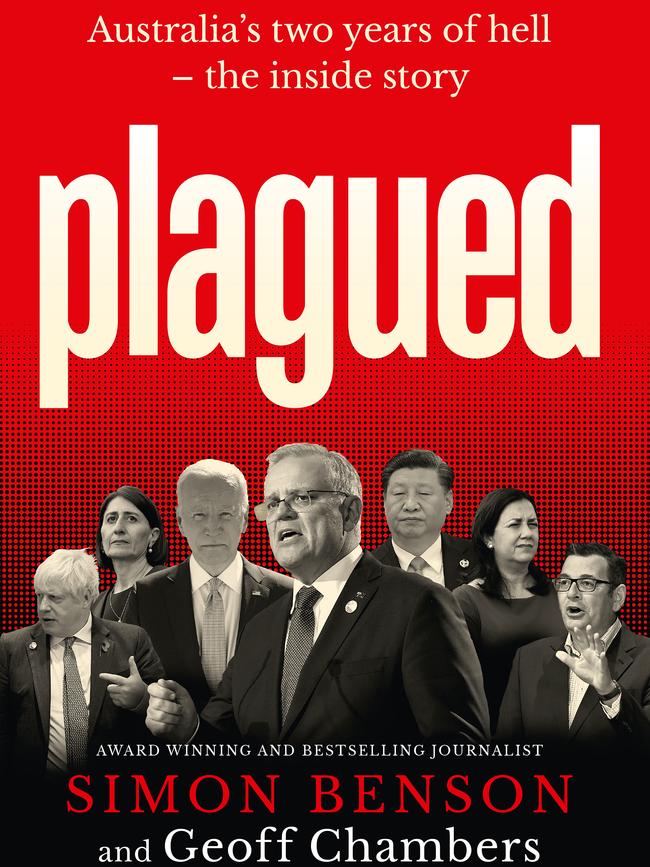

Plagued: Scott Morrison and the decision to close the border to China over Covid

In the second extract from the book Plagued, the arrival of a mystery disease forces our leaders to make almost unthinkable decisions.

On Saturday, February 1, 2020, two days after laying his father to rest in a private ceremony, prime minister Scott Morrison sat in his study at Kirribilli House, the Gothic twin-gabled prime ministerial residence on the shores of Sydney Harbour.

He was facing a decision no prime minister before him had been forced to contemplate outside wartime.

Morrison had made up his mind that Australia would have to close its borders to China. It was only a question of when.

Morrison was by then acutely aware of the potential for an escalation of Covid-19 cases coming into the country, which in turn would cause an explosion of local infections.

Up until that morning, closing the border to China would have been unthinkable, the consequences too far-reaching, economically and politically. But overnight, US president Donald Trump had announced that his administration was doing just that.

Australia’s diplomatic relationship with China was already strained. The decision in 2018 to ban Chinese tech company Huawei from the 5G network, and the urging by Australia for its Five Eyes partners to do the same, had enraged Beijing.

It was the beginning of an accumulation of unjustified grievances the Chinese Communist Party levelled against Australia.

Morrison was acutely aware that closing the border to two-way traffic with China would prompt an even fiercer reaction. But there could be no compromising on public health. Morrison reached for his phone. It was time to speak with his health minister.

When Greg Hunt picked up, Morrison could hear shouts and whoops in the background. Hunt was at a son’s cricket match at Balnarring, not far from his home at Mount Martha, a semi-rural coastal township on the Mornington Peninsula, about an hour southeast of Melbourne.

“We’re going to have to call a National Security Committee meeting today,” Morrison told Hunt. “I think we need to close the borders (with China).’

“I was about to call you,” said Hunt. He’d only just finished a conversation with (chief medical officer) Brendan Murphy, who was also in Melbourne. “Brendan and I have spoken, and we said the same thing.”

A three-way call was then set up between them. Murphy repeated to Morrison what he had told Hunt – that he had reviewed the epidemiology from overseas counterparts overnight. The virus had spread to every province in China.

“If we want to stop this happening here, we need to shut the borders to China,” Murphy told them.

Morrison said he wanted Murphy to get the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee ready to meet by midday, ahead of a meeting of the National Security Committee he was going to call for 2pm. Hunt and Murphy both hotfooted it to the Commonwealth Parliamentary Offices at Treasury Place in Melbourne where they met to dial in to the NSC meeting remotely.

Morrison headed to the CPO building on Bligh Street at Circular Quay in Sydney where he had access to a small, highly secure room, one level up from his office. From there he could take command in front of three video screens.

One of the first calls Murphy made that morning was to Home Affairs secretary Mike Pezzullo, who was pushing a trolley full of groceries in his local Coles store in Canberra.

When Murphy told him Morrison was closing the border to mainland China, Pezzullo didn’t bat an eyelid.

“The initial closure will be for 14 days,” said Murphy, adding Morrison doubted the measure was going to be as short-term as that.

Since late that January, Pezzullo and the relevant agencies had been putting plans in place for a worst-case scenario.

He left Coles immediately, wasting no time setting the wheels in motion. The border closure decision was made, so the only question was how quickly he could get it done.

At the 2pm NSC meeting, Pezzullo told Morrison and the committee that the border closure to China could be in place that night.

Murphy outlined the latest evidence – that cases of the virus were growing outside Hubei province – with significant human-to-human transmission.

What he was hearing had changed his view of the situation. He now believed China was under-reporting cases and mortality, and he recommended that Australia go immediately to a level four “do not travel” alert for the People’s Republic of China, not just Hubei province.

Murphy also told the NSC that while there was some discussion in the scientific and medical community about whether the virus may have escaped from a laboratory, the wet market theory still seemed the most plausible.

But the main focus of the meeting was operational, on what to do and how to get it all done.

Morrison predicted some of the state premiers would be opposed to the border closure so he said he would call them, reminding them that this was a commonwealth decision, and that he would not be swayed.

Morrison stayed back to phone New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. At that point, New Zealand was taking its cues from Australia.

The two leaders discussed the need for such a drastic step as shutting off travel to and from China. Ardern agreed and informed Morrison that New Zealand would shut its border to China as well.

Later that evening, Murphy and Hunt flew from Melbourne to Canberra aboard “the VIP” – shorthand for the RAAF’s fleet of Boeing business jets. They arrived at the National Incident Room just before midnight and worked into the early hours of the morning with deputy chief medical officer Paul Kelly on solving the logistic challenges they knew were coming. Supply chain issues for medical equipment were chief among them.

Morrison knew the impact of the actions he was about to take.

“Closing the Australian border (with China) was a big deal. We knew it was shutting down tourism and international students,” Morrison later recalled.

“It was a huge decision. Even at that time, we were thinking, ‘How do we get back to normal?’. Is it temporary? How quickly can we open it up again?’

“It became apparent that it was just the beginning.

“In the initial phase we were thinking of letting international students in, but by that afternoon the AHPPC said ‘no’. I was terribly worried about the economics: I knew it was going to hurt.”

Then-treasurer Josh Frydenberg recalls that the economic threat first hit home for him in Saudi Arabia, where he had flown for a G20 finance ministers meeting on February 22, 2020.

“The Singaporean and South Korean ministers were both speaking about the impact the Covid was having on their economies,” Frydenberg said. “At that stage we were confident of a budget surplus.

“The Singaporeans, who are well known for budget discipline, were saying how it was driving them into deficit, and so I was thinking about what the impact would be back in Australia.

“At that point no one was anticipating what was to play out over the next 12 months, the depth and the extent of the economic shock.

“At that point everyone thought it was temporary.”

Two days later, Morrison warned cabinet to brace for what may come: the economic impacts on the March quarter were shaping up to be significant.

“We have to socialise the true health nature of the virus,” he told cabinet. “If it goes pandemic, we are going to have some very difficult decisions to make.”

Morrison had just given the first hint to cabinet colleagues that, eventually, Australia might have to extend its selective border closures and ultimately shut off human traffic to the rest of the world.

On Thursday, February 27, Morrison emerged from a three-hour NSC meeting to warn the public that the threat to Australia had suddenly escalated.

After speaking to Murphy, who had come the conclusion the epidemiology spoke for itself, Morrison made a big call to leap ahead of the World Health Organisation.

In the two weeks it then took the WHO to make its official declaration that this was a global contagion – a pandemic – the virus had already begun to cut a deadly path through Europe.

Like many Australians, Morrison was badly shaken by the television footage coming out of northern Italy. He and his wife had been enjoying a rare quiet evening at The Lodge when he’d glanced at the screen.

“It was terrifying. I was looking at that, and if I needed a reminder of what this was about, that was it,” he said. “I told Jenny, ‘There are just going to be corpses on the street’. I felt the scale of the devastation. I thought, ‘We are about to see what this thing does’.”

At an April 20, 2020 meeting, the NSC proceeded to map out a plan to address the calls for an inquiry into the virus and problems with the WHO.

Morrison would write to like-minded countries to solicit support for increased transparency over the health agency. He flagged using a technical committee of the World Health Assembly, the WHO’s 194-member governing body, whose policies were set by the health ministers of member states.

Getting the numbers was going to take considerable diplomatic effort.

With the task set, Morrison concluded the meeting: “Let’s get working on that. I’ll call the UK prime minister.”

Boris Johnson, however, was still on leave after a life-threatening bout of Covid-19. It wasn’t until May 3 that Morrison got to Johnson, out of hospital but still convalescing, asking if the UK would lend weight to Australia’s push for an inquiry into the origins of Covid-19.

“Yes, of course. I want to know where it came from as much as you,” Johnson replied emphatically. “The thing almost killed me.”

By then, Morrison had already approached dozens of world leaders to enlist their support for the cause, one that would test European and African resolve in the face of immense pressure from China.

Some countries were reluctant, publicly at least, claiming that mid-crisis – with the virus ticking over 2.5 million cases and 176,000 deaths worldwide – the time was not right for such an inquiry.

That said, they were all happy if Australia front-ran it.

Morrison’s chief of staff, John Kunkel, later likened the situation to a biological crime scene.

“You couldn’t just say, ‘Look, here’s a crime scene, and we’ll come back to it 18 months later when the evidence has evaporated’,” he said.

Plagued by Simon Benson and Geoff Chambers, published by Pantera Press, is released on Tuesday

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout