‘I’m swearing myself in as health minister, too’: Scott Morrison’s secret plan

Scott Morrison and Christian Porter devised a radical and until now secret plan after concerns he was effectively handing control of the country to Greg Hunt.

No one other than the prime minister himself knew that Friday March 13, 2020, might be the last meeting of the Council of Australian Governments.

Health minister Greg Hunt liked to start his day with a walk, time pressures permitting, and on this particular overcast Friday he began his 6km ritual along his local beach at Mount Martha and up the Balcombe Estuary at 6.45am. Half an hour into it, he received a call from the Victorian president of the Australian Medical Association, Julian Rait.

While Rait was an ophthalmologist, what was more relevant to Hunt was an academic thesis he’d once written on the near fracturing of Australia’s federation during the Spanish flu crisis.

That morning Rait had called to argue strongly that Hunt and the other political leaders of the day needed to draw some crucial lessons from the 1919 pandemic. Chief among them was how federalism almost collapsed when the politicians let themselves believe they were medical experts. They needed a mechanism that put the expert health advice at the apex of political decision making, along with a unified national approach from all levels of government. Hunt swiftly relayed Rait’s observations to Scott Morrison.

The information fell on fertile ground. The idea of creating a new federal structure to bring the two tiers of government together in the battle against Covid had been swirling in the prime minister’s head for several days.

One of Morrison’s goals for the COAG meeting – due to start in hours – was to get all the state and territory leaders to fall in behind the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee and the difficult decisions that would have to be made, regardless of the differences among the jurisdictions. The summit was being held 20km west of Sydney’s CBD in the new soundproof conference room at the Western Sydney Stadium in Parramatta. The commonwealth’s Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy was upstairs in a separate venue room waiting to chair a meeting of the AHPPC via video link with the state and territory chief health officers, looking at the pros and cons of staged restrictions over coming weeks to contain community outbreaks.

He came downstairs to show the COAG leaders the latest round of modelling on the virus with a slide presentation of the infection curve and the incursions and community outbreaks in some states.

“It’s looking worrying,” he told them.

“At some stage we will have to look at physical distancing measures and shutdowns. But that’s probably a bit of time away yet.”

When he returned upstairs to kick off the AHPPC hook-up, Murphy quickly realised that the state and territory chief health officers were moving rapidly in their thinking. They wanted to start shutting down the country that day.

“I’ve just told the premiers that we might do that in the coming weeks, but not today,” he told them.

Murphy then texted Morrison’s health adviser Alex Caroly and told him to send a message to Nico Louw, the prime minister’s executive officer. “Tell the PM I need to talk to him.”

Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy and Reserve Bank boss Phil Lowe by that time had already taken to the floor to brief the premiers and chief ministers on where they saw the economic numbers heading. Kennedy gave a solemn presentation on how dire things could become. Until now, he had been predicting a sharp V-shaped economic recovery but, as he told them, “The economic impacts have changed”, and what he was predicting now was a very long and drawn-out U. Given that, the commonwealth could not be expected to do all the heavy lifting, he told the group. The states had to open their balance sheets as well.

When it was Lowe’s turn to talk, he explained that unlike during the GFC, the central bank’s monetary policy levers were extremely limited with interest rates already at a record low, and the RBA having no desire to go to the negative interest rates that some countries had moved to.

Outside of quantitative easing – colloquially known as “the printing of money” – the RBA had little room to manoeuvre.

His message to the premiers was as unvarnished as Kennedy’s: “Let the stabilisers work; do not tighten your fiscal policy (don’t raise taxes); do what you can on infrastructure, schools programs, roads; and provide stimulus to support businesses.” In effect, he urged them to pump-prime their own economies.

COAG meetings were always long and intense, but that Friday a parallel narrative was unfolding elsewhere. NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian, seated next to Morrison, kept getting texts from her staff updating her about new case numbers, which were being relayed by the NSW chief health officer, Kerry Chant, and she shared them with Morrison. The virus was in lift-off mode.

Watershed moment

Around 2pm, the leaders had broken for lunch. Louw found the PM and passed him a note revealing what had happened in the AHPPC. This would affect that weekend’s sport, pubs, cafes, the lot.

“Where the hell did this come from? You’d better get Murphy back in here,” the PM said to Louw. When Murphy came back down, Morrison left the room to talk to him privately. “What the hell?” he snapped at the CMO. “This is a 180-degree turnaround!”

Morrison then took a minute to process what he was hearing. “We have always said we would take the health advice,” he then said to Murphy. “But you’ll need to explain this to them,” he added, pointing into the room where the state and territory leaders were.

Fuming, Morrison went back into the main room and ordered all staff and advisers to leave. He then gave Murphy the floor.

The AHPPC was now recommending that all outdoor gatherings of more than 500 people be banned with immediate effect, and it wanted to place restrictions on indoor gatherings too. Murphy told the premiers that the proposal was a response to the coronavirus numbers they’d been seeing throughout the day, and that several state chief health officers were even more aggressive, pushing for a complete shutdown, no events at all, indoors or outdoors.

Murphy picked up on the exasperation in the room and he undertook to go back upstairs to tell the AHPPC that if they were going to advise the leaders to start closing the country down, they needed to explain the what, the where and the how to them first.

Despite reservations that the AHPPC was making things up on the run, all the leaders agreed to the 500-person limit, but they wanted more time to talk through the 100-person limit on indoor gatherings.

WA Premier Mark McGowan believed the AHPPC’s advice was too ad hoc and that it was essential for the states and the commonwealth to reach a coherent position before the meeting broke.

“We are going to have to meet more regularly,” he told his colleagues. “We’ve got to work this out now; we can’t just go out there and make these decisions having not worked through all the consequences.”

McGowan’s words struck a chord with Morrison. Morrison had already come to the conclusion that COAG was not armed to deal with a pandemic. This was a watershed moment for the prime minister. Nodding, he said: “We will need to be meeting on everything from now on.”

And, on the spot, he made his call and proposed a national cabinet. This was met with unanimous support from the premiers and chief ministers.

As of that moment, the management of the crisis changed.

“Let’s meet on Sunday and get a formal recommendation back from the AHPCC that answers all these questions we have for them,” Morrison said.

In Morrison’s words, they had just gone “from zero to 100”. The AHPPC’s advice to shut down large parts of the economy had taken them all by surprise.

Louw had been waiting outside the main function room with the PM’s other advisers for the meeting to wrap up when the doors opened and Morrison hustled out.

“We are doing a presser,” Morrison bluntly told his team, sending his media staff into a flurry. There would be no prep time. They were straight into it. “You should probably call a cabinet meeting to agree what you’ve just announced,” Louw told his boss.

As Louw watched C1, the PM’s commonwealth car, pull away from the stadium, with Morrison and John Kunkel, his unflappable chief of staff inside, he realised none of them would be going home just yet.

With Parramatta’s high-rises receding into the distance, Kunkel took a call from Craig Maclachlan, chief of staff to home affairs minister Peter Dutton. Eyes wide, Kunkel turned to his boss: “Dutton has Covid.” Neither man could believe it but their chaotic day had just got worse.

Kunkel made a flurry of calls. One of the first was to the cabinet secretary, Andrew Shearer, to brief him on the outcome of the meeting. After covering off the broader themes, Kunkel dropped what to Shearer – who was in Canberra and hadn’t seen the press conference – was a bombshell: “They’ve also decided to set up a national cabinet.”

“What’s that?” asked Shearer.

“That’s your problem now, mate,” Kunkel quipped.

Secret plan

By March 18, Covid-19 was spreading internationally and in the Australian community. Australia’s daily case numbers were running in triple digits. The pace of the virus was accelerating and with vastly more serious measures likely to be required, Morrison was worried that even national cabinet might not always be able to act quickly enough.

He and Hunt had been considering a drastic measure, invoking the emergency powers – the so-called trumping provisions – under the little-known section 475 of the Biosecurity Act which would empower the Governor-General to declare a “human biosecurity emergency”.

A declaration under section 475 gave Hunt as health minister exclusive and extraordinary powers. He, and only he, could personally make directives that overrode any other law and were not disallowable by parliament. He had authority to direct any citizen in the country to do something, or not do something, to prevent spread of the disease.

Morrison knew that if he asked the Governor-General to invoke section 475, he effectively would be handing Hunt control of the country. If they were going to use them, Morrison wanted protocols set up as well as a formal process to impose constraints. The protocols required the minister to provide written medical advice and advance notice of his intentions to the national security cabinet.

However, Morrison wasn’t satisfied, feeling that there needed to be more checks and balances before any single minister could wield such powers. One option was to delegate the powers to cabinet, but attorney-general Christian Porter’s advice was these powers could not be delegated and could reside only with the health minister.

Morrison then hatched a radical and until now secret plan with Porter’s approval. He would swear himself in as health minister alongside Hunt. Such a move was without precedent, let alone being done in secret, but the trio saw it as an elegant solution to the problem they were trying to solve – safeguarding against any one minister having absolute power.

Porter advised that it could be done through an administrative instrument and didn’t need appointment by the Governor-General, with no constitutional barrier to having two ministers appointed to administer the same portfolio.

“I trust you, mate,” Morrison told Hunt, “but I’m swearing myself in as health minister, too.”

It would also be useful if one of them caught Covid and became incapacitated. Hunt not only accepted the measure but welcomed it. Considering the economic measures the government was taking, and the significant fiscal implications and debt that was being incurred, Morrison also swore himself in as finance minister alongside Mathias Cormann. He wanted to ensure there were two people who had their hands on the purse strings.

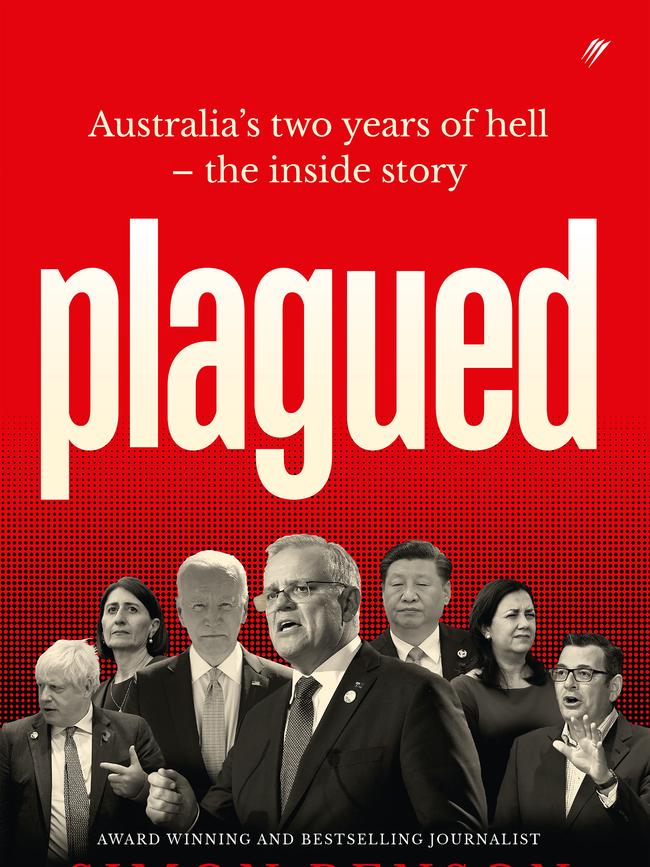

This is an edited extract from Plagued by Simon Benson and Geoff Chambers, published by Pantera Press. Out Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout