Peter Dutton’s Liberal Party crisis: it’s time to fight back

The party faces its biggest calamity since formation. Many Liberals shun this language as hyperbole. But they misconceive the challenge.

Many Liberals shun this language as hyperbole. But they misconceive the challenge. The worst mistake Liberals can make is to assume that when Anthony Albanese suffers a popularity hit and his government begins to struggle that support for the Liberals will automatically bounce back. That is most unlikely.

The reason is because the Liberal predicament is the loss of confidence in the party’s values, policies and brand.

Many people assumed in May last year the problem was Scott Morrison. While hostility to Morrison personally was decisive in the defeat, it only masked the deeper structural issues.

The Liberals suffer an intellectual and organisational crisis underpinned by demography. During a range of interviews conducted by Inquirer a central theme emerges – the Peter Dutton-led party needs to engage in a major review of Liberal policy for a new age.

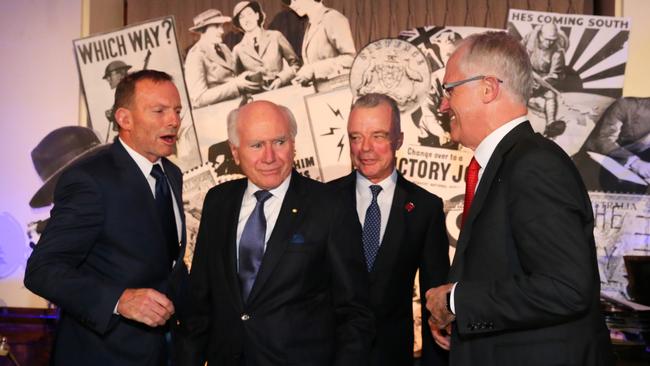

Both opposition immigration spokesman Dan Tehan and former Liberal leader Tony Abbott invoke the spirit – but not the details – of John Hewson’s Fightback agenda from 1991. While Fightback was not an electoral success – it helped lose an election – it put policy steel and meaning into the Liberal Party and a number of its elements were implemented by the Howard government.

Fightback is being invoked to highlight the need for the Liberals to find renewed policy resolution and identity.

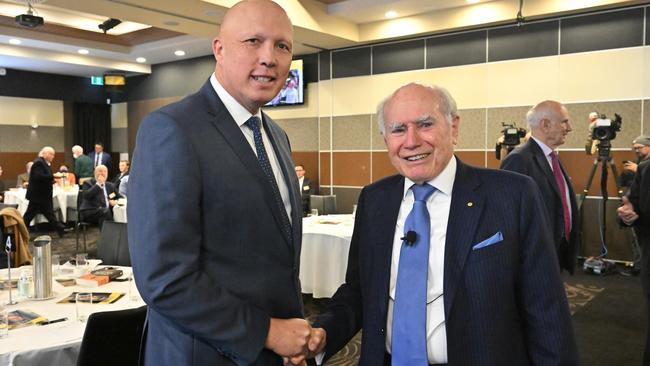

In interviews John Howard and former Liberal Party director Andrew Robb call for a policy review. Dutton, interviewed for this article, pledges a bold policy agenda for the next election and says a reset of policies is already under way.

There is no gainsaying the urgency. The Liberals are going backwards at speed. Nearly a year into Albanese’s first term the current trajectory points to the Liberals losing seats at the next election. Nothing is ordained but the Aston by-election loss may cast last year’s federal election loss as a mere way station to further decline.

The most recent Newspoll shows the Coalition in a worse position on the two-party-preferred vote than at last year’s election – but the deeper damage comes on the primary vote where the Coalition headed Labor 35.7 per cent to 32.6 per cent at the election but now trails 33 per cent to Labor’s 38 per cent.

Surging with confidence, the Prime Minister says Australia is changing and our “political system has changed substantially”. The Aston by-election saw a government win a seat from the opposition for the first time in more than 100 years. Albanese believes he can carry the voice referendum without bipartisanship, another smashing of historical norms. Progressive commentary is filled with discussion about a remaking of Australian values.

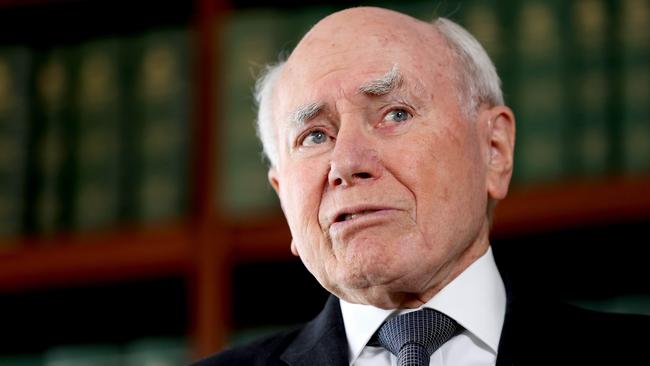

“This idea the country has changed fundamentally, I don’t buy it,” Howard tells Inquirer. Invoking Mandy Rice-Davies, Howard says of Albanese: “He would say that, wouldn’t he.”

However, the Liberal Party internal report on last year’s election conducted by Brian Loughnane and senator Jane Hume says the 2022 result “is not comparable to any previous one in Australian political history”.

That suggests the political earth might be moving. The report says the Liberals have been reduced to four out of 44 inner-metropolitan seats. Most alarmingly, it says the party’s problems are not new. Indeed, they “have been constants for a decade or more”.

That’s chilling – and backed by the data. The collapse in Liberal voting support among all women, notably professional women, and among young voters has been known for years and has not been confronted. This suggests a party suffering paralysis.

As Howard argues, the “single largest failure” of the Liberals at the election last year was the absence of “a clear policy manifesto for the future”. This points to something deeper – a crisis of conviction. That crisis plagued the party for much of its recent time in office. The Liberals have been losing the battle of ideas, even when they won elections. Now they are losing elections as well as losing the battle of ideas.

The Loughnane-Hume report warns of the malaise in Liberal state divisions, saying some divisions are “not in an acceptable position to contest the election in some key seats”. There is a rot within, still largely unaddressed.

What is to be done? Tehan says the need for the policy review is urgent, that it must be wide-ranging and “draw on the best and brightest minds on the centre-right of politics”. He says the review needs to look beyond the parliamentary party for input. He says: “It should have five key themes: lower taxes, higher productivity, smaller and more efficient government, an immigration plan in the national interest and home ownership.”

Given the intellectual crisis facing the centre-right in the US and Britain and the elimination of every Liberal government from the Australian mainland, an ambitious Liberal policy agenda is imperative. It will be difficult in the extreme – yet there is no choice.

The opponents will be strong, saying “stay calm, don’t take risks, wait for Albanese to fall over” – and it’s the false choice. Any review based on internal tokenism won’t do the job. The review can’t be the 1980s recycled. It must slot into the need to win the votes of women, young people and multicultural communities – if it doesn’t do that it fails.

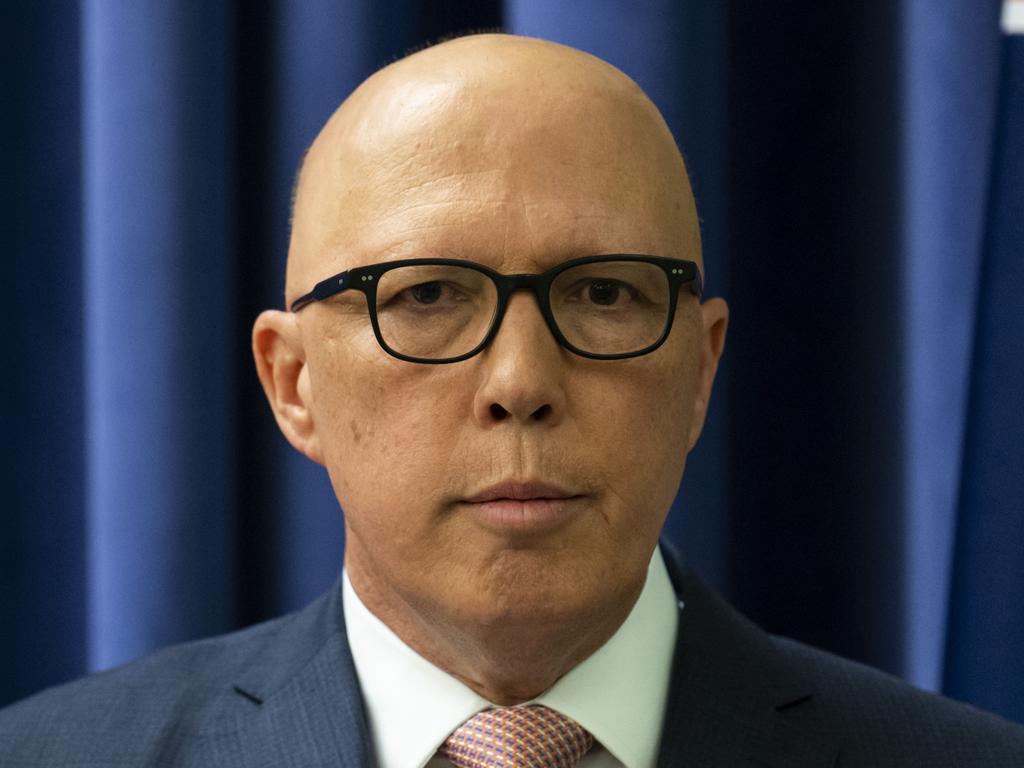

Liberal leader Dutton has been successful in holding the party together (until Julian Leeser’s resignation), but he will find policy change and organisational reform is perilous.

Dutton knows his main task is to restore conviction to a party beset by internal division and loss of confidence. Is it possible? His fate will rest largely on his ability to reform and renew the party.

Interviewed by Inquirer, the Opposition Leader makes two broad promises: “We won’t be a small target at the next election. We will have a bold policy offering that reflects our values, and the work to reset our policies is already under way. We will need to have a sharp, alternative policy offering in place before the election.” Dutton says the stance he has taken on the voice – a Liberal position based on values and principle – mirrors the approach he will take on policies.

In relation to the corrosion in state divisions, Dutton says: “We need to have candidates preselected early, campaigning and connecting with communities. If there’s not an improvement from the state divisions there’ll be federal intervention. I’ve made that clear to state presidents, particularly in NSW and Victoria.

“I won’t tolerate the incompetence we have seen in the past. There’s all sorts of advice from factional warlords but factional warlords are part of the problem. I won’t be taking gratuitous advice from them.”

Analysing the party’s decline, Dutton says: “We need to understand how we’ve ended up in this position. It’s important to be honest with ourselves. From the time that Tony Abbott was deposed by Malcolm Turnbull the Liberal Party hasn’t stood for any substantive policy formulation. The Morrison government was defined by the response to Covid and by AUKUS and did a sterling job in both areas.

“But there was no major policy offering at the 2022 election. So over the period from Abbott losing the prime ministership we allowed ourselves to be defined by our opponents. We’ve done that because we haven’t been speaking to policies that reflect our values. I intend to address that in a very determined way.”

The Loughnane-Hume review says that in the prelude to last year’s election the Liberal Party “had lost control of its brand”. There is no more damning comment – in truth the party, for several years, has been defined by its enemies. This is still the situation and it guarantees defeat. The Liberals need a restoration of politics and policy if recovery is possible.

“Political parties that don’t have clear positions of their own end up simply responding to someone else’s agenda,” Abbott tells Inquirer. “The Liberal Party badly needs to develop a new policy agenda based on the party’s enduring values.”

Abbott calls for a resurrection of the spirit, not the content as such, of Hewson’s Fightback manifesto. “In Hewson’s day frontbenchers and the leader’s office led the policy work, but a great deal of the analysis and modelling was done by supportive outsiders,” Abbott says. “Something like this is needed again if the Liberals are to have the plan for Australia that could win an election.”

The Liberal Party lacks the intellectual resources to pull off an ambitious policy review. It needs to recruit external brain power – and fast. Again, the test is whether the party’s crisis is sufficiently recognised.

Howard tells Inquirer: “I think we have to avoid the error of just waiting and hoping for Albanese to fall over. I am very much in favour of a policy review. The Liberal Party should not pretend things will naturally come back without a lot of hard work. Whether you call it a broadbased policy review, that’s beside the point. We do have to focus on policy.

“We must go back to tax reform. You know my views on industrial relations reform and I think the Liberal Party has been spooked on IR reform for the past 15 years. We have to say a lot more about the home ownership issue. It’s closely linked to middle-class prosperity and the history and traditions of the Liberal Party going back to the Menzies period.”

Robb says: “Successful politics is rooted in good policy. What’s appropriate now is different to what was appropriate 10 years ago. At the last election defeat, many of our people didn’t turn out. They had lost all confidence in the prime minister combined with the absence of any sense of future direction. What is required now is the reaffirmation of the longstanding principles of the party.

“I think the high priority for Peter Dutton becomes a major policy review to update our agenda. That means as time goes by and the Albanese government faces more difficulty, the Liberal Party has a set of strong, developed policies to put before the people.”

Tehan tells Inquirer the party must think along the lines of Fightback as a recovery strategy – that means a “modern manifesto” to reflect the party’s enduring principles. Even to suggest the name Fightback is risky, but that underlines the core problem: the Liberals have been risk-averse and even their supporters don’t know what they stand for. The cycle needs to be broken.

The Coalition is being defined by its stance on Labor’s bills and policies. That is partly inevitable after a defeat.

Dutton’s decision to lead his frontbench into rejecting Albanese’s referendum on the Indigenous voice and stand by the classic liberal principle of human equality regardless of identity is filled with risks – but there is no “safety, safety” revival tactic for the Liberals.

“Crash through or crash” – Gough Whitlam’s famous description of his tactics – is not the approach Dutton should adopt. But a touch of Whitlam’s resolution on party reformism wouldn’t go astray. The current Liberal crisis is the most far-reaching dilemma either of the major parties has faced since the Labor tribulations from the late 1960s when Whitlam warned that Labor’s survival was at issue.

Dutton needs to deliver speeches outlining a strategic response to what the entire country knows – the Liberal Party is at a crossroads. People who think the Liberals should repeat Albanese’s successful small-target tactic from last year’s election don’t appreciate the Liberal situation today is different from Labor’s situation after its 2019 loss. If the Liberals play safe now, they exit via the back door.

Abbott lists several areas the policy review should cover.

The focus should be “serious research” into the things that should matter for a centre-right government – better schools, making the health dollar go further, cutting red tape that smothers economic activity, greater emphasis on hard science and practical trades, addressing unaffordable home ownership, making universities genuinely intellectually elite, dams to deliver the most water for the least environmental disruption and how to best boost hi-tech industry.

Dutton tells Inquirer a policy process is already under way, led by shadow cabinet secretary, Marise Payne, that involves engagement with shadow ministers and working with a unit established in his office already looking at policies and costings. Whether that will suffice is a serious issue.

Dutton repudiates what he calls the “romantic theory” beloved of progressive commentators that the Liberals must adopt Labor/progressive climate, social and cultural policies to recover lost ground.

He says this thinking flourished under Turnbull’s leadership but the predicted support “never materialised”. With such commentary now a critique of Dutton’s leadership, he calls it “a fool’s errand”.

“The idea that if we make ourselves more like the Labor Party then people will end up voting for us is fallacious,” Dutton says.

Yet the challenge Liberals face arises from the economic and social zeitgeist – the trend, accentuated by the pandemic legacy, is towards bigger government, higher spending, compassion-based policies in relation to health, aged care, the National Disability Insurance Scheme and Medicare, with the search for stronger revenues to finance rising public expectations.

The age of market-based reform and productivity enhancement coming from Bob Hawke, Paul Keating and Howard seems long gone.

RedBridge Group research director Simon Welsh tells Inquirer: “The Liberals are losing the millennial vote and we know the millennials are become the dominant political cohort through natural attrition. The millennials are going to dominate in those contestable urban seats, and among the younger voters the Liberal primary vote is 20 per cent on a good day. With that vote you just can’t win seats.

“These younger voters coming through are not asset wealthy, unlike the asset-rich boomer generation. That lack of wealth, particularly housing wealth, means: what have they got to conserve? How do you convince them to be conservative if they’ve got nothing to conserve?

“What we’re seeing is a social progressiveness tied to an economic progressiveness.

“Normally you would expect people in their late 30s to become more conservative because they have assets to conserve, but that’s not happening.

“The challenge for the Liberals is marrying ideology to policy and politics. Government has now become such a big part of the economic aspiration story. People keeping looking to government. They say, we don’t want an American-style society, we don’t want an American-style economy, no laissez-faire, no hands off, US style.”

Albanese tapped this sentiment at the election last year while also pledging fiscal prudence. Labor has been running on this message with different degrees of success since the 2014 budget. The task for the Liberals is to find a new fusion between their principles and the policies needed for a changing country.

Asked about the future for the Liberals if they stay on the same trajectory, Welsh says: “On the same trajectory, we could conceivably be talking of the Greens holding more seats in metropolitan Melbourne than the Liberals, that the Liberals become just one of the centre-right parties. From what I’ve seen over the last 20 to 30 plus years this is the biggest problem the Liberals have faced. When they experienced losses like Kevin 07 they had a capability to respond to it. What’s different now is these problems are structural, they’re demographic with economic drivers hard to turn around. It’s an existential issue.”

The Liberal Party risks sleepwalking into decline and marginalisation. The issue facing the party is whether it grasps and is capable of responding to the multiple dilemmas it faces that surely constitute the party’s most serious crisis since its formation by Sir Robert Menzies.