Victoria holds keys to fortunes of Peter Dutton, Liberal Party

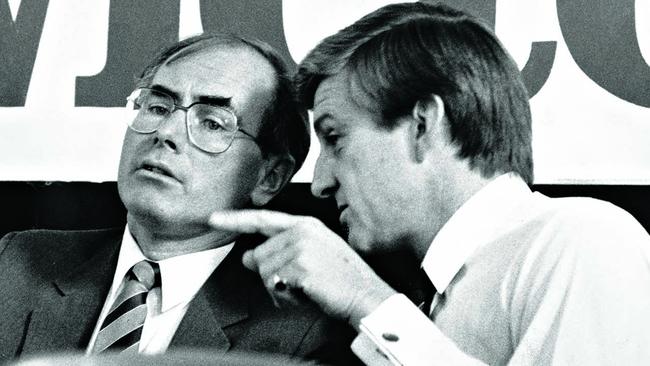

The Victorian Liberal Party is on its knees and is central to Peter Dutton’s aims to win the next election, according to Jeff Kennett.

The solution is urgent: “Fix the party.”

Kennett, for decades the strongest voice in Liberal politics in Victoria, is one of a growing caucus of party figures watching in bewilderment as the party cascades deeper and deeper into crisis, the Aston by-election result just the latest setback.

Its talent pool, organisationally and in the parliamentary parties, is shallow.

“The question is how you respond to that,” says Kennett. Sometimes you’ve got to lose and learn from the result and rebuild.”

There is a real sense – fear, if you are a Liberal – that the Victorian party has dropped too deep into an abyss of failure that it may never come back, having ignored warning after warning about Australia’s most progressive state changing at warp speed.

The challenges are so vast that they have the potential to rival the effects of the 1955 Labor split, which supercharged the Liberal Party at Labor’s expense for years.

The first warning flare was set off in Victoria in 1994 when the Greens’ candidate, Peter Singer, secured 28 per cent of the primary vote in the by-election for the federal seat of Kooyong.

Five years later the three inner Melbourne Liberal seats – Kooyong, Higgins and Goldstein – would vote overwhelmingly for a republic, way above the national average.

Then in 2017, an even stronger progressive result with the same-sex marriage vote; the evidence, as far back as the 1990s, was there of a cultural divide in inner Melbourne. It’s a fair bet the results would be replicated on the voice, which Dutton has opposed in its current guise.

This Liberal crisis is not isolated to Victoria, with the federal opposition now holding only four of the 44 inner metropolitan seats across Australia’s major cities, according to the party’s 2022 federal review.

Of the seven federal Liberal seats left in Victoria, just two are in the eastern suburbs. The east was once largely safe conservative suburban heartland.

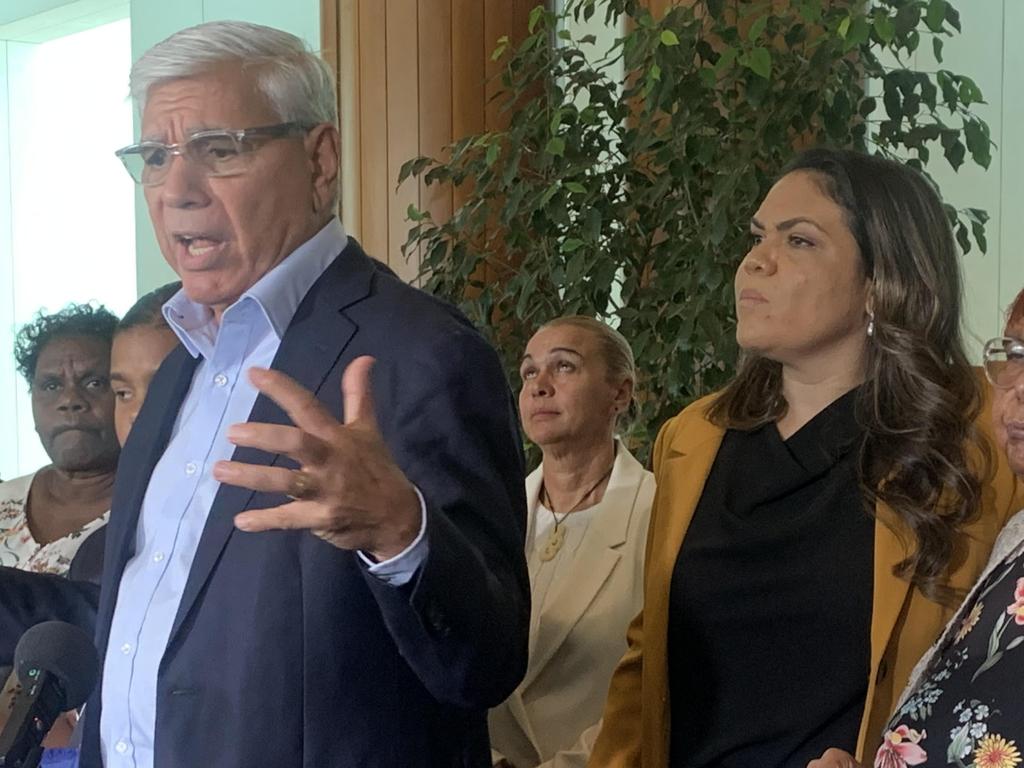

“Our values are terrific,” Victorian party president and former senator Greg Mirabella tells Inquirer. “But we haven’t translated them to meaningful policies. It’s got to start somewhere.”

The tale of why Victoria is different (but not alone) is in the numbers, a sharp shift in demographics that has coincided with the dominance of the political landscape by Labor since 1999.

The state Coalition has held office for just four turbulent years of the past 24 years – between 2010 and 2014 (Ted Baillieu and Denis Napthine).

In so many ways, the Victorian Liberals created their great nemesis, Dan Andrews, leaving behind a budget in rude health for Labor in 2014, which the party used to bludgeon the former government to a pulp.

Andrews was in Victorian Labor headquarters after the 1999 republic referendum result; he and others around him were alert and alarmed about the rise of the Greens and the threat it posed to mainstream party values held by the ALP and even the Liberals. Indeed, Labor was all over the demographic changes, deciding early in the 2000s to focus heavily on population growth. Comedian/businessman Steve Vizard, with the Bracks government’s imprimatur, ran a full-blown summit in 2002 on how to bring more people into the state.

No surprises that many of these people have voted Labor. Big time.

No surprises that Andrews’ aggressive left-wing social policy agenda has been used both to cut off a large-scale Greens invasion but also to woo hundreds of thousands of younger voters. At the Liberals’ expense.

Victoria’s population has grown to more than 6.5 million, up 1.5 million since 2006; the Kennett voters have died off in their hundreds of thousands; and a new generation of voters is starting to dominate – millennials and Gen Z.

All just at the historical point when Melbourne is predicted in less than a decade to become the nation’s biggest city. The biggest city maybe, but culturally divorced from Sydney.

John Howard had his battlers in the 1990s but in Victoria – ahead of the national average – the state has a new class of university graduates that number more than double that of technicians and plumbers, builders and motor mechanics.

According to demographic services company .id, in 2021 there were nearly 1.6 million people with uni qualifications in Victoria, up more than a million from 20 years earlier. A quarter of the state is listed by .id – using ABS statistics – as professional, the very people who have moved out to Melbourne’s outer electorates, like Aston, where cashed-up tradies once dominated.

Deep in this demographic earthquake, people of Chinese and Indian ethnicity now make up nearly 11 per cent of the state, up nearly 200,000 people in 20 years. Lose one of these groups and it’s game on in seats like Aston.

The great mystery of Victorian politics is how Dan Andrews went on to secure a thumping 56 seats in an 88-seat parliament at the 2022 election.

One senior Labor source said an important key to Andrews’ success is the super-sizing of the health sector, almost 330,000 health workers now hover over the political debate in Victoria. During Covid, Andrews spoke directly to these people, every single day. Many are nurses.

“Guess who Dan threw his weight behind?” said one Labor elder. “He spoke to them relentlessly and made decisions that supported them. Lockdowns, for one. The Liberal Party has no way back with this group.”

At the same time, one in every 10 workers in Victoria is in the broad public sector, or nearly 345,000 people. The ratio is marginally higher in NSW.

While the inner public service is about to get whacked because the Victorian budget has blown up (more on that later), the southern mainland capital is awash with Labor-voting bureaucrats.

“They (the Liberals) are facing a challenge which is not cyclical,” says Kos Samaras, a director of polling and lobbying firm RedBridge Group, and a long-time Labor campaigner. “There has been the birth of a new middle class.”

Add to that the looming dominance of younger voters and there is a long-term toxic cocktail for conservatives, he says.

“They are not going to vote conservative,” he says of the new era of young, university-educated voters. “They will not win these voters over.”

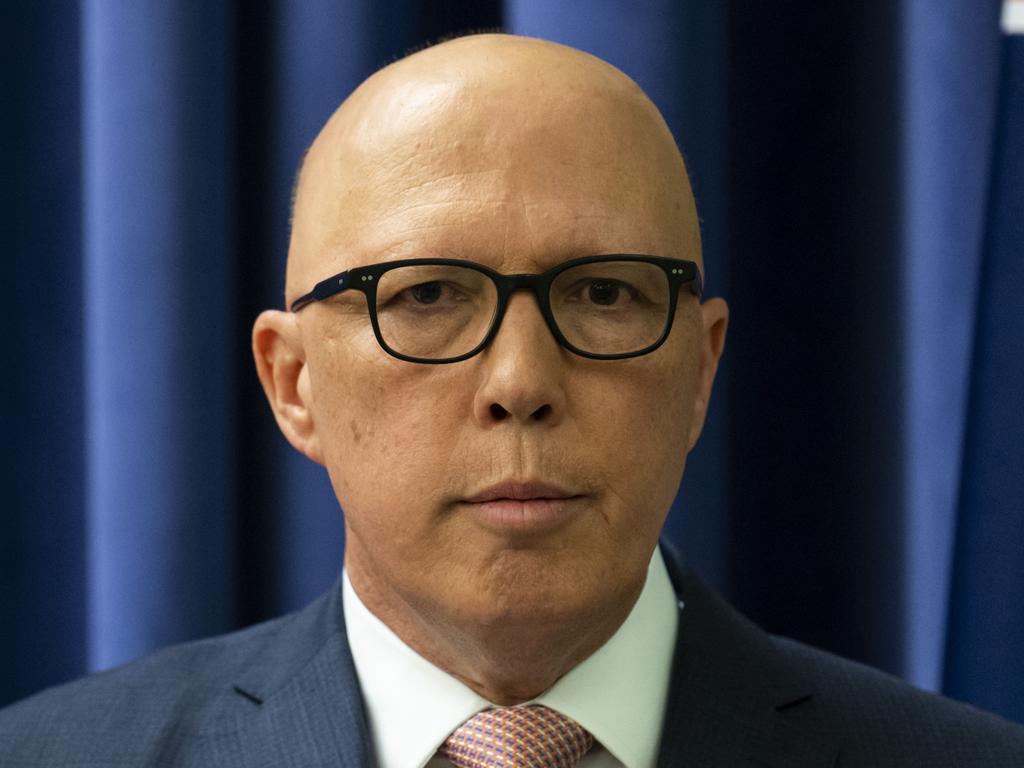

Peter Dutton desperately needs the Victorian Liberal Party to fire up (not explode) and he won’t get progress without the ground-war infrastructure a successful state parliamentary party would give him.

Dutton has been counselled to consider backing federal intervention in the state branch, which is being resisted by the current leadership. The party needs business talent to show an interest in its fortunes; the next generation’s version of Hugh Morgan, the former Western Mining boss.

The state parliamentary party is at war with itself over anti-transgender reform activist MP Moira Deeming, who was suspended for nine months but, sources said, is most unlikely to return to the Liberal parliamentary fold.

The 19-member administrative committee, which runs the party between rank-and-file conferences, is widely viewed as dysfunctional and often incompetent. Prone to leaks and infighting.

Behind the scenes, senior figures want an urgent injection of political talent on the committee. Few of the 19 have serious political experience.

One exception is the most senior federal Liberal, Dan Tehan.

Tehan, a former campaign strategist in the Liberal secretariat, also backs the party’s core beliefs, which are rooted in the power of the individual, the power of democracy and the power of private enterprise.

“You’ve got to trust your values,” he says, mirroring Mirabella.

But he also believes the party’s capacity to cannibalise itself has come at a high cost at a state level, with very real fears Victoria is about to enter a second “Cain-Kirner”.

This refers to the John Cain and Joan Kirner Labor era of financial disasters that smashed the state’s finances and hammered the Hawke government in Victoria just over 30 years ago.

“There is a real fear that Victoria is heading to the exact same challenges that were faced with Cain and Kirner,” Tehan warns. “The state is becoming unfinancial.”

Faced with this huge political opportunity, the state parliamentary party became embroiled in a fight with a then virtually unknown MP, Deeming, that threatened the authority of a relatively new leader, John Pesutto. Pesutto understands well the perils of inner-city Liberal life, having lost and then regained his seat of Hawthorn.

Kennett was disgusted that many of Pesutto’s colleagues failed to back their leader, regardless of what they thought of the decision to kick out Deeming. “Unity and sense of purpose is so important,” says Kennett. “They should have expressed that privately and supported him fully.”

Kennett wants an injection of new talent into the party in both an organisational and parliamentary sense, with the dead wood discarded, along the lines of his powerhouse AFL club, Hawthorn. He says while Victorian Labor has gone through internal upheaval over branch stacking that forced federal intervention, there was not the same room to move in the Liberal Party, with its philosophy based on the individual rather than the collective.

“We have no capacity to do that,’’ Kennett laments.

After most elections – state and federal – reviews are undertaken to help make sense of what has gone right or wrong; the 2022 federal review was conducted by former party director Brian Loughnane and Senator Jane Hume. It pinpointed macro issues including the party’s long-term problem with women and the emergence of the inner-city disaster that manifested in the rise of the teals.

Despite another rout, the Victorian state party is not conducting a review into the 2022 poll disaster that gave Andrews yet another go at it. But stroll back through the pages of the 2014 review conducted by former federal Liberal minister David Kemp and the 2018 review by fellow party elder Tony Nutt and the same themes emerge.

Nutt is not capable of a short conversation and his 119-page amalgam of 2014 and 2018 reads like a Dick and Dora, plain-English guide on how to win an election. It is a root-and-branch guide on how to campaign, how to administrate, how to formulate policy, what emphasis should be placed on data, the need to attract more women MPs and voters, how to manage booths, build better relationships with the media and the timeline upon which these things should be executed.

It also records the various internal disasters, chief among them the theft of $1.5m worth of party money by former director Damien Mantach, which had a cascading impact on the party it has largely not recovered from.

The party and the state parliamentary team were so divided in 2018 that there were effectively two campaigns, to disastrous effect.

Then there are the African gangs. In 2018, then home affairs minister Dutton lamented that Victorians were “scared to go out to restaurants” because of African gang violence. This was nonsense. This comment coincided with the state party’s law-and-order campaigning and it failed miserably at the polls, fundamentally because people didn’t believe it.

As Nutt noted in his campaign review of the law-and-order strategy: “Regrettably, the post-election market research study shortly after the campaign showed only 6 per cent of the voters claimed that it (law and order) actually influenced their vote, and then not necessarily to our advantage.”

Fast-forward to 2023, and the state party has been tripped up by transgender issues. While an important policy issue, it matters little to the overwhelming majority of voters. “They are a tenth-order issue. No, 13th-order issue,” a frustrated Liberal MP said.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has left the state’s finances in historically poor condition and a ruthless spendathon by state Labor has coloured its major projects balance sheet a vivid red.

Nutt’s review painted a pathway to internal stability and electoral success.

Now Labor’s refusal to contain its spending even after the pandemic is over and the budget is shot has provided the clearest possible opportunity for a Liberal resurrection in Victoria.

But is the party up to it?

Jeff Kennett has some sobering advice for the Liberal Party’s federal leader. “For Peter Dutton, the key to the future, in my opinion, in so many ways, is getting Victoria right,” the former premier says.